This is possible!

5th anniversary of the red state teachers’ rebellion, part two

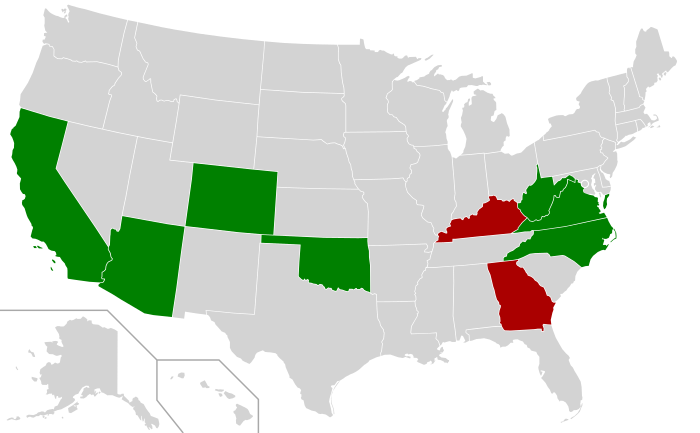

In 2018, rank-and-file educators, largely through the use of statewide Facebook pages, helped lead and coordinate strikes of tens of thousands of educators in the traditionally Republican-led, right-to-work states of West Virginia, Oklahoma, and Arizona. In addition, mass sickouts and one-day rallies occurred in other Republican-led states like Kentucky and North Carolina. These strikes, which came to be known as the “Red State” strikes, helped inspire workers in other industries to also strike, turning 2018 into the year with the highest number of workers on strike in the U.S. since 1986.

Twenty thousand West Virginia teachers started the strike wave in late February with their nine-day strike. In a state where teachers ranked 48th out of 50th in teacher pay, they won a 5 percent pay raise for not only teachers but all public employees in the state. Two different times they rejected proposals that would have given lesser raises to other public employees and continued their strike. Rank-and-file teachers took the lead in organizing both the lead-up to the strike and the strike itself by setting up a Facebook page, West Virginia Public Employees United, that at its high point had 24,000 members on it. It’s important to remember that wages and benefits in all these states were determined by the Republican-dominated state legislatures so organizing a statewide strike was imperative for any success.

Next up on April 2, Oklahoma teachers shut down two-thirds of public schools in the state for just over two weeks affecting 500,000 students. In the build-up to the strike, the Republican-dominated legislature passed a $6,000 pay raise for all teachers to try and avert the strike. In a state with the lowest average teacher wages in the country, where many starting teachers earned as low as $31,000, what amounted to roughly a 20 percent pay increase for some was unprecedented there. In Oklahoma at the time, only 34 percent of teachers were organized in the state affiliates of the National Education Association and American Federation of Teachers. That’s why just like in West Virginia, it was crucial for rank-and-file educators to organize themselves through statewide Facebook pages like Oklahoma Teachers United and Oklahoma Teachers Walkout. While the Oklahoma legislature refused to restore funding for schools after years of cuts and teachers were unable to win pay raises for all public employees, the high point of the struggle, when 50,000 people rallied on April 9 at the Capitol in Oklahoma City showed the widespread support for teachers there.

In Kentucky, some 12,000 teachers and public employees rallied at the State Capitol on April 2, shutting down schools in all 120 counties. (100 were closed because it was spring break, the rest because of a one-day sick-out.) In North Carolina on May 16, some 30,000 educators, public school workers, and supporters rallied at the State Capitol in Raleigh in what was the largest teachers’ mobilization in the state’s history.

The final major statewide strike occurred in Arizona starting on April 26 and ending on May 3. Like in West Virginia and Oklahoma, teachers in Arizona were woefully underpaid. The Morrison Institute for Public Policy found that Arizona had the lowest-paid elementary school teachers in the country when factoring in the cost of living, and that high school teachers ranked 48 out of 50. Over the course of about two months, a team of less than 10 rank-and-file educators–most of whom hadn’t even met previously–built a rank-and-file educators group from the ground up that eventually spread across the state and led a statewide walkout of some 60,000 educators.

Primarily through the Arizona Educators United (AEU) Facebook page with over 45,000 members, educators created a network of 2,000 liaison educators in at least 800 of the roughly 1,500 schools around the state. With the support of the state’s main teachers’ union, the Arizona Education Association (AEA), they united teachers, counselors, librarians, school bus drivers, school psychologists, office staff, academic coaches and other staff. When compared with the Republican governor’s initial funding plan of only $65 million in new funding, the final amount of around $400 million in new funding which included an average of around 10 percent pay increases for teachers was an enormous victory.

2023 marks the 5th anniversary of the “Red State” strikes. To both celebrate the inspiring victories, and attempt to learn valuable labor organizing and strike lessons both for educators and other workers around the U.S., Tempest interviewed four educators and leaders of the strikes in West Virginia, Oklahoma, and Arizona.

Nicole McCormick was a teacher and Vice-President of her Local during the nine-day 2018 statewide strike of 20,000 teachers in West Virginia. She was a self-proclaimed “shit stirrer” who helped moderate the Facebook page West Virginia Public Employees United which led the build-up to and strike itself. Currently, while no longer a teacher, she works remotely advising Education majors. She also organizes with the statewide educator caucus, West Virginia United, which was born from the original Facebook group and strike.

Steph Price was a Speech Language Pathologist (SLP) in Oklahoma during the 2018 statewide Oklahoma teachers strike. Currently, she’s a SLP in Washington state and the Secretary of the Federal Way Education Association. In addition, she helps lead National Educators United.

Dylan Wegela was a teacher in Arizona and one of the main rank-and-file leaders of Arizona Educators United which led the statewide strike of 60,000 educators in 2018. In the leadup to and during the strike, he helped coordinate site liaisons. His role was to help train, guide, communicate with, and organize site leaders, who then would go on and organize their schools. Since the strike, he moved back to his home state of Michigan. After teaching for a year and a half, he ran for state office. He’s now in the Michigan House of Representatives representing District 26 in Michigan, which is Garden City, Inkster, Southeast Westland and Northeast Romulus.

Rebecca Garelli was a teacher and also one of the main rank-and-file leaders of the 2018 statewide strike in Arizona. She created the original Facebook page Arizona Teachers United which later became Arizona Educators United. She helped coordinate and develop the escalation plan and the 8-week organizing blitz that led up to the strike. Since the strike, she quit teaching in the classroom and served in the role of Science and STEM specialists at the Arizona Department of Education for the last four years. She recently transitioned to being a full-time self-employed consultant providing professional learning for science for districts across the state of Arizona. She was also a teacher and part of the Chicago Teachers Union strike in 2012. Currently, she helps lead National Educators United.

Elizabeth Lalasz contributed to this interview. She is a registered nurse and steward with National Nurses United.

Part two

Darrin Hoop: What’s your favorite memory of the strike–something that just sticks with you, makes you smile, or makes you think about how awesome it was?

Nicole McCormick: Mine was kind of painful, but it led me to a moment that changed me as a person and how I looked at everything. My husband and I had four children at that time, all under six.

We both taught, and he still teaches. We went to the babysitter’s house because we were going to go to the local picket lines. We didn’t go to the Capitol because it was too expensive. We didn’t have the money. We were living off $15 a day after we paid our bills and that was supposed to be for gas, food, and diapers for two babies. Our youngest two are only five months apart.

So he walks the kids in. I’m sitting in the van, and over NPR I hear that the strike is over and the union leadership has made a deal with the governor. I remember gripping the steering wheel, and I can feel it in my hands right now. I just lay my head against it and sobbed. Matt came out and I was still crying and he asked, “What’s going on?” I said, “They made a deal with the governor. It’s not even their jobs that are on the line, it’s ours. You know what I mean?”

I just remember being so just completely overwhelmed. There are a billion reasons that I love my husband. But he looked at me and he said, “I don’t give a damn if we’re the only people there tomorrow. We’re going to stand out on that line together.”

So, it was one of those moments of just solidarity between us. Then I was mad and began to think, “They’re not going to do this.” So we went to the local picket line and I had the state union president’s cell phone number. I gave it out to every single person that I could. I said, “You need to call him and tell him you’re not okay with this. You’re not going to go back. Make sure you share it with other people, too.” I don’t know how many texts and calls he got, but I know I gave it out to at least 150 people because I went to one picket line and then we went out to another picket line because there were two main ones in the county.

I just remember that feeling of, we’re not going to go back. I went from utter despair to seeing everybody being pissed and everybody saying, “I’m not going back. Who thinks they can tell me to go back?” I was like, “Oh God, we’re not going to go back.”

We had this map of West Virginia where, whenever counties closed [in the strike vote], they turned red. The counties just slowly started turning red. There was even a woman who had a geography map and she colored them in and it was first to close, last to close.

I think that was probably the most exciting moment in my life. I was just like, “Oh my God, there are three counties left. There’s only one county left.” I remember thinking, “I can’t believe we bucked our own leadership and were able to shut down the state.” It was just that moment, I get chills talking about it right now. There was this moment of power and of me feeling like I am my own person. I know what I’m talking about. I don’t have to get permission from anybody. I mean, it was just life changing. I didn’t know a lot of the people whom I consider to be my closest dearest friends. I didn’t know them before the strike. Now I’m thinking, I would trust my life to them because of what we went through together.

Rebecca Garelli: It’s really good. I have three things that I often think about. The first one is, Dylan, you and I were standing holding the sign at the march, and I remember you looked at me and you said, “This is so amazing, you know?” and we just hugged each other and we were sharing snacks from my bag. Remember I brought snacks. Then we did what we called water solidarity. We picked up all the cases of water and passed them back down the line, because it was 110 degrees outside, but UFCW brought water. We were literally passing cases behind us, down this massive march.

I’m just looking at Dylan thinking, “This is crazy. This is what’s happening.” Then when we turned the corner to come in and I saw the metal stage that I didn’t know the NEA paid $80,000 for. I was floored: “Wait, what?” This didn’t feel grassroots anymore. I was a little taken aback by the monstrosity of the metal stage, quite frankly. I remember just thinking, holy crap.

Then the Red Fred band was on the stage, and the music started, and everyone was dancing and cheering, and it was 110 degrees. I got up on that stage and I chanted for the first time, and there were 75,000 people following me. I just never want to leave that space in my whole life. I just want to live in that space of being the person who yells on stage and gets everybody fired up. So that was like my second moment, right? It’s just like being in that. I don’t want to be anywhere else except in that moment for the rest of my life, just with everybody feeling the same vibe. Yelling at the legislators behind us. I’ve never felt such power in my soul, just burning through my soul.

We had an organizer’s tent. We were in the tent, while everyone was camped out on the lawn. I will never forget what this lady said to me. She walked up and everybody was kind of weird. People came and took pictures with us. It was kind of awkward, but this woman came, she’s decked out, head to toe in homemade signs, with stuff on her head, just like the whole nine, and she said, “You know, I’m 50 years old and I’ve lived in Arizona my whole life and I didn’t know that we could do any of this. I was always told not to ruffle feathers.” I was just thinking, “Wow, you’re 50 and you’re down here as an educator and you didn’t know you were allowed to do stuff like this?” Multiple times over the organizing when people were like, “Am I allowed to wear a red shirt? Am I allowed to put things on my car?”

I said, “Of course you are. It’s your right.” I didn’t understand it fully until she was in my face going, “I’m 50 and I didn’t know we were allowed to do this.” I can just see her in my mind right now. It just really sets the tone; the stigma of speaking up in Arizona is so deeply rooted here that you just don’t speak up here. I’ll just never forget it.

Dylan Wegala: I have a few moments. I think the first one is when we announced our demands at the very end of the rally, and we got everyone to turn their camera light on. Being on stage and just seeing all of the lights, all these little lights in the distance, coming towards us on the stage in solidarity was kind of just like, “Wow, okay. Everybody is really here and really united.”

I think I told this story the other day, Rebecca, but on one of the nights of the budget hearings, when it went deep into the night, I actually left to go to a Justin Timberlake concert with my wife because I had bought her tickets for her birthday and I just couldn’t miss it. But I came back and everybody was still there. At three or four in the morning, Noah K. and I got led into the minority leader’s office, Rebecca Rios. We were just lying on the floor. We both fell asleep and woke up at 4:30 a.m. and thought, “All right, we have to go home.” I know that’s such a silly memory, but it was me and Noah just sleeping on the floor of this office. We came back the next morning for an event.

The last moment was just being in the room with all the people who organized when we announced the strike vote results. It was just that feeling. I don’t know how to describe it, but it was like one validation of me pushing the union to say, “Hey, this is what people want to do.” I just remember everybody’s celebrating there, both the union and all of our grassroots.Those are my brief three moments that I just really, really loved.

DH: Shout out to Noah Kavalis, one of your fellow AEU leaders.

Stephanie Price: It was a really emotional time. I think every day I was angry and crying and laughing, you know? It was just this overwhelming amount of emotion. One of the things that I think is important to note about the strike in Oklahoma was that the legislators tried to prevent the strike by giving teachers a raise and we were like, “Fuck no. We want education funding. Our students deserve more. Our public employees deserve more.” So we went out anyway.

One of the days, I actually had a child support hearing and I called and said, “Hey, I’m on strike and you know, it’s important for me to be here. Can I join by phone conference?” So when I called in, the woman who was on the phone said, “Thank you, thank you for what you’re doing,” because the strike affected them. It was an increase in their pay too, for state employees. It wasn’t just about educators. She told me how much it meant to her that we were out fighting for her too. They couldn’t be there. They couldn’t strike. But that we were there meant a lot. So that was really powerful to me.

I remember the very first day, this was for me as a person who’s nervous, I have my kid with me. I’m coming in on this gigantic bus that they’re transporting people from the parking lot. I’ve never been on strike before. I don’t know what to expect. Almost instantaneously after walking off of the bus, there’s this announcement that says, “Hey, everybody, stop. There’s a kid who’s lost. The mom got on the speaker saying, “Hey, everybody get down.” You could just see the entire crowd lower. Just everyone stopped, paused, stopped talking, got down on their knees, and the mom said the kid’s name and, “Where are you? Mommy loves you, can you hear me?” They found him almost immediately because of course, here we are, all these educators, these people whose job it is to love and protect children, just completely stopped what they were doing to make sure this kid was safe. That stood out to me as like a really powerful moment. It was just incredible.

DH: How did the strike end and what did you win or not win? Maybe there are some things that you still wish you had gotten that you didn’t get. So how did it end? What did you win or wish you could have won more of?

DW: When the strike ended, the union called a meeting letting us know they were going to call the strike off. It was kind of one of those meetings where there’s already a determined answer, but you talk about it, just to talk about it anyway. I pushed back on that.

So, what we did win wasn’t technically a 20 percent raise, but that was the way that it was sold to us. We saw an increase in funding to make that happen. I can’t even remember all of the other things. I think really what we want though is people learning how to organize.

In Arizona, I think some of that has been maintained. Some of that maybe has faded, but I think ultimately what you win in general on strikes such as these are, it’s one more chip at the establishment way of thinking that things have to be this way all the time.

People believe that they are more powerful than they ever have felt before. I think some of that is echoing through until today where we have workers organizing. People are still looking back to what we did saying, “Hey, this is possible. That is something that you can’t put a number on and that it is the only thing that’s going to save this world and this planet.”

But ultimately, there’s a lot that we didn’t win. Maybe Rebecca can talk about some of that.

People are still looking back to what we did saying, “Hey, this is possible. That is something that you can’t put a number on and that it is the only thing that’s going to save this world and this planet.”

RG: Yeah, we won $434 million in education funding from a GOP legislature, which is a pretty huge win. Then yes, the ridiculous 20 percent by 2020 plan. People got pretty significant raises in some places, but in others not so much. Out of the five demands we got, one of them was met for the most part.

The other four were for classified employees. We basically had to split our pot with them, which is a division tactic. We had to divide our funding with them. So, it’s a partial win, but that’s a division tactic.

We wanted salary structures being put back in because those were taken away during the recession. We did not win that. So that means every year you get a step, and then as you get degrees, you get lanes, so vertical and horizontal. Then a moratorium on the tax credit. So no more tax credits for corporations. So that’s why we pivoted to the ballot initiative because the ballot initiative invested the resources that would have actually met those demands, and that was the lever to pull and make that happen. But that didn’t happen, as you all know.

DW: I’ve actually taken that demand of no tax cuts to Michigan with me. I did it first with corporations and I lost. But I don’t think people know what happens over the long term. I’ve been trying to talk to my colleagues about that.

DH: Before Nicole goes, is there anything you want to say that you haven’t already said about how it ended in Arizona?

DW: Well, I think after we did this Fox survey at the Capitol people were happy. They wanted to go home. I think at that point, that battle was lost. We did, I think, convince them that we were going to stay out until the budget actually passed, because there was a conversation not to do that. Then we started putting these in different amendments. This is where the amendment strategy came in, to just continue to put pressure on the institution.

I think the strategy from the union was to move to electoral politics, which is where we went with the ballot initiative–that is a whole story in itself. Two times collecting signatures and twice being thrown out after the vote and then once before the vote. It’s just maddening.

DH: Nicole, what did you win or what do you wish you would have won that maybe you didn’t win? Do you want to say anything about how the strike ended?

NM: So there was charter legislation that we killed. We won a 5 percent pay increase for all public employees, even those who didn’t strike with us, which again, talking about a dividing tactic, they tried to tell us, “Oh, here’s your pay raise.” We were all like, “Eat it.” As Stephanie was talking about, we refused a pay raise in 2019 for them to kill privatization. We said, “We don’t want your money. We want you to kill this.” But we won that 5 percent pay increase.

I know that there are other things I’m forgetting, but there was a task force set up for PEIA and to be real frank with you guys, they passed a huge increase this year, 26 percent increase in premiums. There’s a spousal penalty if your spouse has access to other healthcare – $150 a month. So people said, “Ah, God, I can’t afford this.” I mean, a starting head cook in 2018 in one of the counties that bordered mine made $20,000 a year, my very last year of teaching.

I taught for 12 and a half years, and I have a master’s degree. The highest pay I ever earned as a teacher was $48,000. That’s criminal. I got an $11,000 pay increase to leave the classroom, and I was a good music teacher. I needed a break, but I really feel that I could have come back if the wages had been sustainable and class sizes would have been what they’re supposed to be.

But I really wish that we would have won a real fix to PEIA funding. About half the counties in West Virginia, half of the land in those counties are owned by out-of-state corporations and entities. There’s a North Carolina logging company that owns the most amount of land, and they pay pennies on the dollar that regular folks that pay.

We’re a resource colony, an extraction colony, we always have been. So they come in and take our resources and our people and everything else and just kind of leave us like we are on strike. So, I can’t remember how late it was, but finally on the 11th day they finally signed the legislation giving everyone a pay increase and killing the charter legislation.

It felt like a very brief celebration. Then everybody, they just kind of melted. Oh my God, I was so tired. It had been so hard. It’s like winning a hard fought game or something, like a football game. At the end of it, you’re just like beaten and bruised and just kind of limping back to your car. That’s how it was. I’ve had people describe this strike as almost feeling like they were in a war. Like they felt like they went to battle. It was a lot to unpack, having all these emotions. One day I didn’t realize what a big deal it was and I went to Labor Notes and I came back and I was describing the experience at Labor Notes and I literally just broke down and sobbed.

I was in the break room at work and I remember sobbing for 30 minutes. Somebody had to go watch my class. It was just all of this stuff that we’d been holding onto.

SP: Yeah, it was hard to go back after they ended the strike. It was hard to go back knowing that we had won some things, but not everything we wanted, knowing that there was a good chance that things weren’t really going to change in the long run.

RG: I felt a lot of those emotions too.

SP: You know, overall we did win a pay raise, a $6,000 pay raise for educators. I want to say it was around like $1,200 for support professionals, plus the funding for the state employees and some education funding. There were certainly things that we won. We were waiting and ready to push for more. We wanted to see changes to capital gains taxes for the wealthiest folks in our state who were not paying their fair share.

Basically, I started hearing about hush-hush meetings happening between the union and politicians, kind of like they were going to start bringing things to an end, the way it was going.

So we were getting these surveys from our superintendent asking, “Are you going to be here tomorrow?” and everyone was responding, “Nope.” Eventually, one day I got a letter in the middle of sitting in observing a legislative session. I got a letter where the superintendent said, “You’re coming back to work tomorrow. We’re ending your time there.” I replied, “No, we’re not.” Actually, my district did a wildcat strike and almost all of us just showed up at the Capitol again the next day to the point that people from the administration building were in classrooms subbing because they didn’t have educators.

Then, shortly after that, all of a sudden, the union said, “We’re ending the strike. We’ve reached the point where we can’t get any more and we need to call it.” But it was kind of an interesting and perhaps almost shady process where they said that they used the results of a survey that they had sent out, but multiple people have said, “I didn’t get any such survey. I don’t know what you’re talking about. I never saw this.” Also, they had sent this survey to a building where we have no service. There were thousands of us packed into this space. We don’t have cell phone service. We can’t access this survey. Anyway, it was the union saying, “We think our time is done, and you have said as a membership that you’re ready to go back.” Which, hmm. I don’t know that I believe that, but it was disappointing. It was disappointing. A lot of people didn’t feel like they were ready to go back, though. I am thankful for the things we did win. Not enough to keep me in the state, but we won something.

DH: Some of you have touched on this, so if there’s nothing else to add, that’s fine, but is there anything else you want to add about what’s happened to education in your state or city since then?

SP: I shouldn’t be surprised, but watching them elect the exact same kind of leader as the governor who left, the exact same kind of politicians who put us in this situation to begin with, over and over again is surprising. The state superintendent of public education is a white man with very limited education experience who doesn’t really believe in public education. You know, he’s calling educators and union members terrorists. How is that progress? How can you show up to fight for your students and to fight for yourself and see year after year what is happening?

When the politicians are trying to defund public education, but then you still vote for the same kind of people, I know I shouldn’t be surprised, but it’s just absurd to me the amount of mental gymnastics that it has to take to do that. Part of the problem, I really believe, is straight party voting in Oklahoma. The religious push too. It’s just absurd. Teachers in Oklahoma are still struggling, and I’m glad I got out when I did.

NM: You know, we had something like 2,000 vacancies, which we thought was shocking, you know, at our 2018 strike. Now there’s like 8,000 or something crazy like that. So we’re just hemorrhaging education employees, not just teachers. I mean bus drivers, nurses, school aides, everyone that is working with students is like, peace out, I’m done.

It’s beyond just the profession too. We keep on bleeding the population. At the time of the strike, we had five to eight million. Now we’re down to 1.7 million. It’s only been five years. We just constantly lose population. And the things that they have been able to push through are terrible. They are things that I never thought that a traditionally blue state would allow to happen. They are hateful and vicious and they hate everyone who doesn’t look and act and think like them.

It’s really difficult to stay and fight, which is sad because West Virginia is this unique and beautiful place. Anytime I’ve ever bumped into a West Virginia outside of West Virginia, we embrace and we say, “Oh my God, another West Virginian.”

It feels like you’re part of this little teeny tiny club. Every time that they do any type of research, no matter people’s economic standing or their political persuasion, West Virginians overwhelmingly identify as defiant. I mean, that’s a badass quality to have, to feel that you’re constantly having to defy the people in charge. I think it was you, Rebecca, who was talking about the woman you talked to who didn’t realize that it was okay or even a possibility to stand up and fight back.

It’s these people who are used to having to fight for everything, for their food, for their water, and then they still get a straight ticket. National politics, the fundamentalist religion vote, and these people are destroying things.

As for education, I don’t think it’s hit rock bottom. I think that we still have a ways to fall as a nation, but I think it’s heading that direction. I think it’s going to come to a crisis point where parents realize there’s no one to watch their kids. It’s the same thing with health care. I think it’s going to come to a crisis point where there’s nobody to take care of the sick and the dying, people will wonder, “Oh what are we going to do?”

RG: I’m sure you’ve seen what’s happened here. It makes national news all the time. We have the first universal voucher expansion program and my former boss is the new superintendent of public instruction.

This was Doug Ducey, our villain, right? During RedForEd they called us a political circus. This was his golden ticket. The legacy that he left behind was this universal voucher system. Well, we have a democratic governor and won a lot of things. So it looks like Arizona’s purple, but we’re not. The legislature is still controlled by one seat in both chambers, so it’s still a GOP majority.

Our governor had run on capping this universal voucher program in which every parent can get $7,000 per child. There are people who homeschool their kids. I live in a community where there are a lot of Mormons who have a lot of children. Let’s say you’re a mom with seven kids, you effectively can make $49,000, which is more than teachers make, and you can get that at the drop of a dime with no accountability, no transparency. You barely even have to turn in receipts.

So this program, which they projected to be $30 million, is now off the rails. Over 50,000 people have put in for vouchers at $7,000 a pop. This is going to almost get to $1 billion. It is currently sitting at like $687 million. We have a pro-public education governor who ran on capping the universal voucher program. But behind closed doors, he just made a bipartisan budget with no cap in it. So you are going to watch this take off, and the Republicans are laughing in our faces. So every single ALEC lackey in every single other state looks at Arizona. If you can do it here, you can make it work anywhere. So we are effectively going to be in an even worse situation.

There’s more power in building power, in building people power over relying on legislators. We’ve seen that time and again when people compromise. A second lesson is about the idea that the union’s going to do it for you. It’s not going to happen.

DH: What do you think, if you look back on it, what do you think are the most important lessons that you and your fellow educators learned from your experience in 2018 that you could impart to educators or that could be a broader lesson for anybody in a workplace or in a union more generally?

NM: You don’t need permission. Your labor belongs to you. You don’t owe it to anybody, and the more people who you include, when you fight for the common good, you’re more likely to win. I mean, that to me, those are the big three lessons that I learned. I thought I always had to wait on somebody else or I always owed somebody else something, and I didn’t have this idea, even though I should have, I mean, schools are the heart of their community, and I didn’t have this concept of, I should be fighting to make sure that everybody in this town has potable water.

This is a fight that we can take on as education professionals. This is something that’s important to our students. So it took going through that for me to recognize that, when you fight for the common good, you really can win a better world.

SP: I don’t know if Oklahoma won any or learned any lessons. Because look where they are now. I don’t know, I think generally, people saw what could happen when you come together, that educators were the reason that the strike happened in the first place, because they said, “No, this isn’t good enough, we need more.”

That ultimately pushed the union. I think on a personal level, I learned about the power of organizing. I learned what that looks like and why that creates change. I learned that like my voice matters and it is important and I don’t have to be afraid to use it and to speak up for what I believe in.

I had been afraid to use my voice and live into my power because of the toxicity that I had dealt with. That was a really strong lesson that I took away, the power of my own voice and that each of our voices has, and then the power of our voices when we come together.

For me, one big lesson is that legislators are not your saviors. They will drop you at the drop of a dime for a better deal, for a better piece of action. In a caucus, you may work your butt off to elect them. That does not mean they will work for you. it’s not reciprocal, it’s just not.

So you build it yourself and say, “I’m not stopping and I’m going to do this because this is the right thing to do.” We are going to organize ourselves and push the union. You cannot just say, “Well, the union’s not doing it.” We always say, “You are the union.” But I like to take it a step further and say, “You need to show them your power so that they will do things.”

And if they don’t, then take their spot. It’s about building that people power and not waiting for a white knight to come along and save you, because no one’s coming to save you. You’re the only people who can save yourselves. That’s where I’m at.

DH: Elizabeth, did you have something to add?

Elizabeth Lalasz: This has been incredible. It’s about the moment from COVID going forward. People are realizing the significance of the struggle. It’s nurses and workers across industries all over the place. What you all did in 2018 led to larger strike numbers than we’ve seen since that time. But there’s something going on among working people in this country. You just laid out the lesson that we can only save ourselves.

Politicians aren’t going to do it for us. We’ve got to do it and be defiant. Don’t wait for permission. I think about the labor movement right now, like the young people organizing at Starbucks, REI, or at all of the museums. The people who are Teamsters or in the UAW right now.

They need to hear that. This is what people are trying to figure out now in a wider way. You figured it out.

Featured image credit: Wikimedia Commons; modified by Tempest.

We want to hear what you think. Contact us at editors@tempestmag.org. And if you've enjoyed what you've read, please consider donating to support our work:

DonateDarrin Hoop View All

Darrin Hoop is a teacher in Seattle and a member of the Seattle Education Association and the Seattle Caucus of Rank-and-File Educators. In addition, he's a member of Tempest and helps lead National Educators United.