Worker insurgency and the New Deal

The inevitability of hindsight

Eric Blanc has written a series of articles on Substack arguing that the role of the state and electoral politics via a major capitalist party are central to working-class self-activity, upsurges, and union growth.1This series focuses on the New Deal and its role in “spurring” the strike movements of the mid-1930s, labor’s political development, and what these might mean for socialists today. The issues raised in his representation of working-class action and its causes and results in that period involve not only the proposed role of electoral politics or government policy in the labor upsurge of the New Deal, but also bring into question the very nature of working-class self-activity and agency and its relationship with the “facts” of history.

Did 7(a) spur and shape a workers’ upsurge?

Much of Blanc’s argument in the first two parts of his series centers on the role of the National Industrial Recovery Act’s (NIRA) Section 7(a), which stated workers “shall have the right to organize and bargain collectively through representatives of their own choosing,” in “spurring” the 1933 upsurge in strikes.2In Blanc’s second installment, he writes, cautiously at first, “[T]he point here is not that policy and governmental changes on their own spurred a labor upsurge… Internal struggles and organizing initiatives from below did matter” (emphasis in original). He then goes on to claim, however, “The evidence is overwhelming, however, that Section 7(a) played a major role in boosting and shaping the era’s labor insurgencies” (emphasis added). So, worker self-activity mattered, but 7(a) not only spurred action but shaped it, as well.

No one would deny that government actions and policies impact the class struggle, or even, in this case, that the coming of the Roosevelt administration after more than a decade of conservative Republican rule and three years of neglect in the face of the Great Depression itself brought a sense of hope and even of new possibilities for action. If Blanc is trying to argue that the New Deal state was involved in and had an impact on working-class and union affairs, there would be little to argue about except the motivations and outcomes. But he seems to be arguing much more than that. Despite the qualifying introduction, the idea that 7(a) shaped the labor insurgency of the mid-1930s is quite a claim for a policy that proposed no particular form of “representation,” had no effective enforcement mechanism, with influence limited to a “psychological effect” by most accounts, and, as I will argue below, with an initial impact (whatever one thinks it was) that faded rapidly.

Despite a handful of testimonials to 7(a)’s initial psychological effect and a widespread faith in its impact among liberal historians, the argument for 7(a) as a major cause in “shaping the era’s labor insurgencies” simply doesn’t hold up in the face of the timing of events. For one thing, the July-September upsurge in strikes that is supposed to be the result of 7(a)’s passage in June didn’t last long—certainly not for an “era.” As the major Brookings’ study of the NRA (the National Recovery Administration, the administrative body of the NIRA) reports, “From November 1933 to March 1934 the strike movement subsided somewhat and union growth went forward at a slower rate.”3In fact, the number of workers who initiated strikes dropped like a lead balloon by 71 percent in October, 1933, after only three months, even more severely and before the frequent “seasonal” winter decline that usually started in November in those days.4The major reason for this was the return of economic recession: the index for manufacturing dropped 13 points in August, soon followed by declines in the indexes for the number of employed workers and total hours worked. 5In other words, economic reality trumped policy promise and 7(a) lost its attributed “psychological effect” after less than four months.

If psychological inspiration from or government action around 7(a) were really the force behind those engaging in the broader fight for union recognition over this “era,” we would expect more workers to make use of the NRA’s National Labor Board (NLB) representation election procedures, which were established in August, rather than risking a strike in such turbulent times. But the opposite is the case. During the board’s entire existence, from August 1933 through July 1934, just 103,714 workers participated in an NLB election, with 71,931 voting for union representation. During the economic upswing from July 1934 to January 1935, when elections were run by the new and improved National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), only 45,000 workers cast ballots in a representation election. In comparison, 2,624,253 workers struck in 1933 and 1934, 1,227,639 of them specifically for union recognition or a closed shop.6

This imbalance between strikes for recognition and government-sponsored elections meant to head off or settle strikes stemmed in part from the different meaning of recognition for government administrators and rank-and-file workers. For the administrators of the NRA boards or the later 1935 NLRB, as well as for many top union leaders, recognition via elections introduced institutionalized and orderly collective bargaining between union and company officials with an emphasis on wages. In contrast, as Mike Davis noted, rank-and-file workers “fought for two demands that would be central in most early New Deal strikes: company recognition of rank-and-file-controlled shop committees, and the limitation of the authority of foremen and line supervisors.”7Strikes, frequently led by rank-and-file radicals and/or skilled workers were not only a means of winning these, but of building and demonstrating the workplace power of the class.

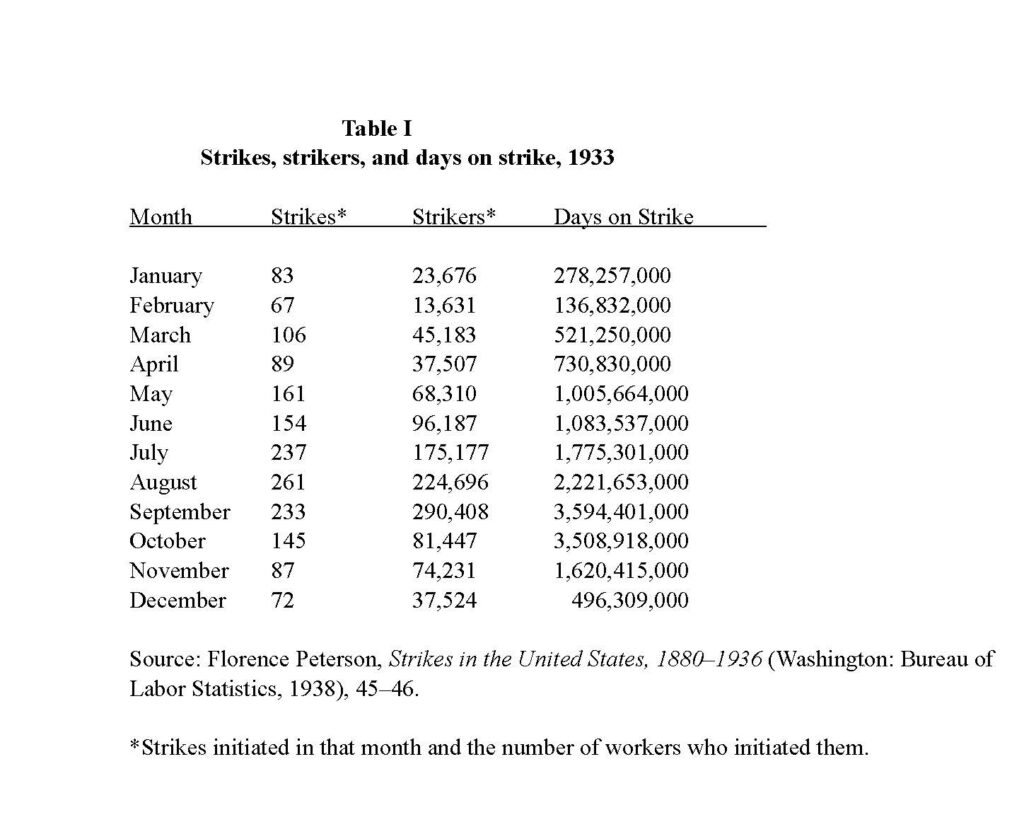

Furthermore, the jump in strike action in July-September didn’t come out of nowhere. As Table I below shows, the number of strikes accelerated in early 1933 before the NIRA and 7(a), which passed in June and was really in place only around July, if then. Prior to this there were several big high-profile strikes in auto in early 1933, mostly led by radicals before June, which created momentum.8As socialist leader A. J. Muste noted of the time, “Early in 1933 Hell began to pop. Strike followed strike with bewildering rapidity.”9Furthermore, some groups of workers organized themselves successfully in 1933 before 7(a) was passed. Despite Blanc’s attempt to disparage their work, Michael Goldfield and Cody R. Melcher have documented in detail the thousands of coal miners who organized prior to the NRA and 7(a) without the aid of United Mine Workers of America staff organizers, much less the government.10

More important than the number of strikes is the number of strikers and days on strike, which give us a better idea of the development of the active element of the class in this moment. As Table I shows, from February to June, before 7(a) could have had even a psychological effect, the number of workers who initiated strikes in each month grew by seven times, while the days on strike increased by a factor of eight. Altogether more than a quarter of a million workers initiated strike action between February and June. This is low compared to what was to come, but high compared to what preceded it, and moving upward.

The economic context also mattered. The biggest increase in strikes and strikers, of course, did come in July as 7(a) became policy. But was it simply this statement of limited intent or even some union leaders’s attempts to use it to encourage workers to join a union that brought more workers out on strike, or did actual material conditions have an impact? From March through July 1933 the economy recovered rapidly and the manufacturing production index grew by over two-thirds from 92 to 154. Leverette Lyon, in a major 1935 Brookings Institution study of the NRA, argued it was the “psychological effect of Section 7(a)” that was most important in explaining this new upsurge. Nevertheless, he also noted, “The new stirrings in the world of organized labor could be explained in part by the combination of accumulated grievances and the economic stimulus of the ‘business boomlet’ of May-June 1933” just before the NRA and 7(a) became law.11

Florence Peterson, in her massive 1938 BLS study of strikes in that period, also gives joint responsibility to economic recovery. She wrote, “The first year of recovery and the impetus for increased labor activity ensuing from the National Industrial Recovery Act doubled the number of strikes in 1933.” Lewis L. Lorwin and Arthur Wubnig in their 1935 Brookings study of labor boards also cite the “business boomlet” as a cause of increased strikes. One of Roosevelt’s most admiring biographers credited the economy rather than the president’s program: “As business improved during 1933, workers flocked into unions.” Thus, along with the previous experience of the active layer of the class, the underlying economic conditions were clearly a major factor in spurring the upsurge—and then its collapse.12

Furthermore, Lyon says even of the 1933 July-September upswing in strikes that it was “intense, often quite spontaneous.” 13Spontaneity, of course, is the explanation for rank-and-file worker self-activity and agency that is often not visible (or believable) to mainstream academics and experts, along with the lack of identifiable, known officials. Would this upswing in strikes have occurred or been as pronounced at that time if there had been no economic recovery or prior working-class experience? As Mike Davis pointed out, the 1933 upsurge “owed nothing to the benevolent hand of John L. Lewis and other official leaders.” Most of the strikes of 1933 were led by “unofficial vanguards” of Communists and other radicals, on the one hand, and skilled workers with “neo-syndicalist craft traditions,” on the other—with the two sometimes overlapping.14Even if we don’t dismiss the initial psychological effect of Section 7(a) altogether, we can see that a significant change in the economic situation, the developing experience, and the demonstration effect of earlier strikes encouraged more workers to seek redress of grievances and protection through organization and strikes on their own—“spontaneously” it seems.

What in the estimate of the Brookings’ NRA study came after 1933—as the economy picked up and strike levels rose again in 1934—is even more significant for the worker-agency, “bottom-up” view, on the one hand, and the diminished power of 7(a) and the NRA, on the other:

“A new wave of strikes and a new upswing of union organizing began in March 1934, reaching a peak in the summer months. There was a new element in the situation which differentiated the movement of 1934 from that of the year before. By the spring of 1934 the labor groups had lost some of their earlier faith in the NRA and even in the NLB as agencies that might be helpful to their cause. There was a growing resentment in labor ranks against continued unemployment, inadequate weekly earnings, increasing discrimination on the part of employers against union workers, and the growth of company unions. The new temper made itself felt in a change of leadership in some unions, in greater pressure upon older leadership for more aggressive action, and in an outburst of labor militancy.”15

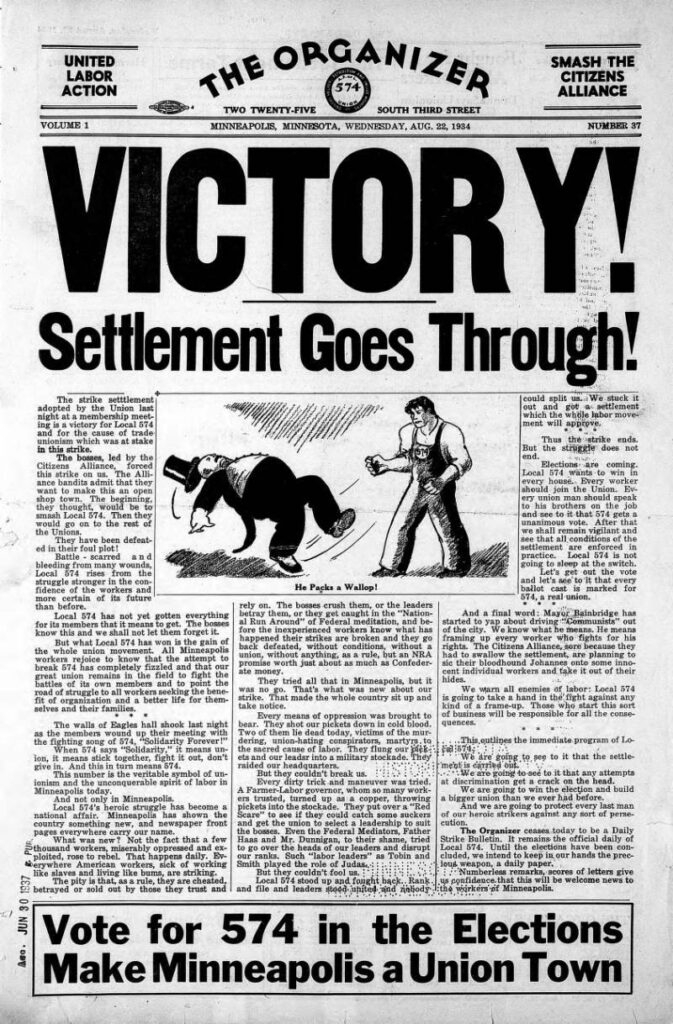

The Brookings description of the 1934 strike wave is an academically cautious representation of the upsurge in which mass strikes led by leftists—notably the San Francisco longshore, Minneapolis Teamsters, and Toledo auto workers—were central. In addition, the 3,000-member strike of Philadelphia/Camden shipyard workers was led by Socialist Party members. All of these strikes also involved community and public mobilizations, often of the unemployed, and actions to pressure local and federal governments, as well as employers. By 1934, major sections of the class now had a larger experienced “militant minority” that was often led by Communist, Trotskyist, Musteite, left Socialist, and other radical leaders and workers to help direct and broaden the struggles. Few, if any, engaged in Democratic electoral politics at that time. Along with earlier strikes by mine, auto, and rubber workers, in particular, this direction included the move toward industrial unionism. To put it another way, because of underlying grievances, material conditions, prior experience, and the growth of a militant minority in many industries from the early 1930s onward, political class formation had advanced significantly by this time and workers were shaping the upsurge themselves—largely bypassing the NLB/NLRB and without any significant mainstream electoral involvement.

The positive effect of 7(a) not only faded rapidly but also did not have the outcome often attributed to it. U.S. union membership actually declined during the first year of NRA 7(a) from 3,050,000 in 1932 to 2,689,000 in 1933, a loss of 361,000 members—despite an upturn in the economy. No wonder workers lost faith in 7(a) and the NLB/NLRB and began calling the NRA the “National Run Around.” In 1934, the second year of 7(a), with workers better organized and led and more workers striking, they recouped the lost membership which rose to 3,088,000 by 399,000 members. This was accomplished overwhelmingly by the strike wave of 1934, in which a total of 762,367 workers struck specifically for recognition, compared to the 45,000 who took part in NLRB elections, many of whom had themselves been on strike.16

Who benefited most from the NRA?

The National Industrial Recovery Act was drafted in May, 1933 at the insistence of President Franklin Roosevelt as a means of stabilizing the economy and restarting growth, not to promote unions. The NIRA structure was based largely on proposals from businessmen like Gerard Swope of GE and Henry Harriman of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, influenced by the First World War experience with War Industry Boards. Section 7(a) was added mainly as a result of pressure from union leaders and was copied from the 1932 Norris-La Guardia Act. By August, the labor boards were formed to handle the growing number of strikes. The reason for this addition was not that the government foresaw another 1919-style strike wave at that time, but, as Irving Bernstein argues, “The government feared that these stoppages would impede the recovery of business” which was the major object of the NRA.17In their 1935 Brookings study of NRA labor boards, Lorwin and Wubnig drew the same conclusion about the need for stability, stating that, as a result, “The Board’s main efforts were to settle strikes.”18

Indeed, the NRA’s new national and regional labor boards intervened frequently where there were effective strikes in 1933–34 with the intent of ending them. That included the mass strikes in San Francisco, Toledo, and Minneapolis in 1934. For example, as the Minneapolis Teamster strike continued in August 1934, the federal mediator who demanded that the union make concessions to end their strike said, “[T]he strike must be settled: Washington insists.” 19The workers rejected the demand for concessions and went on to force the employers to make the concessions instead, winning a significant victory for industrial unionism. The first successful industrial union of the period outside the American Federation of Labor (AFL) was the Industrial Union of Marine and Shipbuilding Workers of America (IUMSWA), which formed in 1933 at New York Ship in the Port of Philadelphia/Camden. As in the other 1934 strikes, the shipyard workers union included socialists in its grassroots leadership. Its 3,000 members struck for over a month that year, completely closing the shipyard and halting Navy ship production. As historian David Palmer summarized the shipbuilding workers’ experience with the NRA, “As early as summer 1933, New York Ship trade unionists learned that they could not rely on either the NRA’s IRC [Industrial Relations Committee] or the NLB to help them win their demands.” The 1934 strike, especially given the importance of Navy contracts, and a union-led public pressure campaign directed at the Department of the Navy won significant gains.20

The NRA did not favor unions over employers, which is one reason that its actual impact was limited to a brief psychological effect. In order to stabilize the economy and establish “codes” for industry, it promised access to the right of self-organization to both sides in the capital-labor relation and encouraged cooperation between the two. Section 1 of the act promised “to provide for the general welfare by promoting the organization of industry for the purpose of cooperative action among trade groups, to induce and maintain united action of labor and management under adequate governmental sanctions and supervision.”21This represented an asymmetric class compromise in which industry received immunity from antitrust laws while workers were given only a vague right to seek representation. Pre-existing trade associations and other well-established business organizations, as well as companies themselves, gave capital a distinct advantage in establishing and dominating industry codes. Where union representation existed in the “code” administration, it was almost invariably with an AFL bureaucrat hostile to industrial unionism, as in the shipyards22

It was actually capital, therefore, that gained greater leverage under the NRA, both in terms of industry codes they dominated and, as we will see below, in the form of company unions. Without restraints on the power of capital, it could hardly be otherwise, given the highly unequal power of capital and labor in the employment relationship. Specifically, as the Brookings’ study of the labor boards concluded, 7(a) “did not require recognition of existing trade unions…as exclusive agencies for collective bargaining,” “outlaw company unions,” or “compel employers to come to terms with employee representatives.”23Even more damning, as Brookings’ Leverette Lyon wrote, the top NRA administrators and lawyers “fostered the self-organization of employers for collective action, while trying to be ‘neutral’ towards organized labor. The NRA thus threw its weight against labor in the balance of bargaining power between capital and labor.”24

One result of this pro-employer bias was that, from 1932 to 1934, company unions grew from 1,263,194 to between 2,5000,000 to 3,000,000 by Lyon’s estimate, at least doubling. Over that same period, the unions, on the other hand, gained a net increase of just 38,000 members. The employers resisted union recognition and genuine bargaining, understanding perfectly “that 7(a) did not exclude company unions as agencies for collective bargaining” and acted accordingly.25That, as Blanc points out, some union members were dragged into these company unions only underlines the imbalance of the law and its administration.

The NRA’s pro-employer bias was illustrated in the case of the all-important Automobile Labor Board. After Roosevelt himself intervened in March 1934, as Bernstein wrote, “The auto companies won a total victory on the application of 7(a) to their industry.”26That ruling, in turn, paved the way for the more complex but even worse NRA setup in the southern textile industry, which was completely dominated by capital and its allies, with the complicity of Washington. Janet Iron’s detailed account of this history describes a workforce that was at first grateful to Roosevelt, the NRA, and 7(a) but rapidly became disillusioned and angry with both the NLB and the board set up to administer the industry code. After reviewing its major rulings to allegedly protect workers attempting to organize, she concludes that the “entire board structure was a charade.”

The textile workers strike, the biggest in 1934, went down to defeat as a result of the United Textile Workers’ leaders’ dependence on the NRA set up, fear of more militant tactics, and reluctance to seek broader alliances. In what Irons called a “revealing epitaph” to the lost strike, Francis Gorman, who was in charge of much of the strike, wrote in 1936,

“Many of us did not understand what we do now: that the government protects the strong, not the weak, and that it operates under pressure and yields to that group which is strong enough to assert itself over the other…. We know now that we are naïve to depend on the forces of Government to protect us.”

To counteract the power of capital, he called for an independent labor party and in the unions “rank and file democracy and collective leadership.”27All a little late in the game.

What about those Minneapolis Trotskyists of Teamster Local 574? Did they, in fact, depend on the government and 7(a) or was it their mass strikes that led to the organization of an industrial union? Blanc cites strike leader and author Farrell Dobbs as saying the declaration of 7(a) “helped along the process of unionization.” The rest of this sentence, however, is crucial: “even though the workers were to find themselves mistaken in their belief that the capitalist government would actually protect their rights.”28Which is just what, as we have seen, happened. This whole quote referred to their organizing in 1933 when, as Dobbs also wrote, the NRA was “newly adopted,” that is, in that brief moment when 7(a) seemed to have some psychological force. The organizing the Minneapolis Trotskyists had been engaged in since 1930 finally led to a strike of coal drivers in February 1934 that forced gains from the employers and eventually led to a regional labor board election they won by 77 percent. The strike, that is, led the board to organize the election. By May, Local 574 had surpassed its craft origins as coal drivers and “some two to three thousand workers in the broad trucking sector were sporting Local 574 buttons.”29Later in the year, it would have about 7,000 members due to its intense organizing and mass strike. The struggle had intensified in 1934—as the Brookings study itself indicated more broadly concerning the “new element in the situation which differentiated the movement of 1934 from that of the year before.”30

Dobbs later writes of Local 574’s leadership’s attitude toward government policy, “Under pressures of such a fierce struggle, maneuvers detrimental to the union could be expected from the Labor Board and from Governor Olsen.” And, indeed, Local 574 and its Trotskyist leaders engaged in numerous tactics in relation to the Farmer-Labor Party and Governor Floyd Olsen, the regional labor board, and the NLRB. The union and its revolutionary leaders stuck by their demands and their militant actions—even when the Farmer-Labor governor imposed military law and arrested many of Local 574’s leaders and activists. What they avoided was a descent into electoral politicking that would have made them dependent on Governor Olsen and his administration and diverted the struggle at that time.

Furthermore, when Dobbs reflects on how the “workers’ illusions about capitalist democracy” played out, it was not the rights under 7(a) or the electoral process that the rank-and-file seized, but that of self-defense in the form of clubs in order to fight the police and deputy sheriffs “club against club.” This they did successfully in May until the governor was forced to call in the employers and the labor board to work out a truce—almost entirely on the union’s terms. In fact, the historic July-August Teamster strike of 1934 led to an NLRB representation election, putting its revolutionary leaders in the minority that used this procedure, and ended in arbitration, which was strictly voluntary under the NRA.31So, while Local 574 took advantage of these NRA institutions, to the workers and leaders alike this was seen as a victory due to a long and hard-fought mass struggle that had forced the employers and the government to accept this outcome. The government itself had no legal power to bring the employers to this outcome.

In the July strike, the strikers forced the hand of the employers, the governor, and the federal mediators and achieved a material result in higher living standards and permanent union organization. The settlement was not a complete and total victory, but it laid the basis for the growth of Local 574 on an industrial basis. Clearly, workers’ agency was at the center of the Minneapolis Teamster story. One has only to read Teamster Rebellion or Bryan Palmer’s Revolutionary Teamsters concerning the conditions and demands of workers, the early organizing that began years before the 1934 strike, the role of revolutionary leaders, the incredible strike preparations and execution, and the shaping of Local 574 from a craft to an industrial union to see clearly that neither the will to strike, the organization to win it, nor the industrial character of the union were dependent on 7(a) or the NRA more generally. Instead, the material needs and growing consciousness of the workers themselves, their revolutionary leaders, and the strategy and tactics they developed to win—that is, worker agency—were decisive.

Minneapolis Trotskyist electoral practice

The Minneapolis Trotskyists’ electoral practice in the mid-1930s followed the building of Local 574 into a strong industrial union and was both limited and contradictory. The Trotskyist Communist League of America rejected working through the Democratic Party on principle. It also did not participate in the nationwide labor party movement of 1935–36 on the (misguided) grounds that the period contained revolutionary possibilities that would bypass (or be blocked by) a reformist labor party. Yet, in 1935 the Minneapolis Trotskyists adopted a policy of “critical support” for Minnesota Farmer-Labor Party candidates. The actual involvement of Local 574’s Trotskyist leaders in electoral politics began with supporting the Farmer-Labor Party’s candidate for mayor of Minneapolis in 1935. In 1936, during their “entry” into the Socialist Party, they backed Norman Thomas for president and ran Trotskyist Teamster activist V. R. Dunne for state office on the Socialist Party ticket, while at the same time offering “a highly qualified endorsement” of the Farmer-Labor Party as the “political party to which labor unions are affiliated.”32

Blanc’s contention concerning 7(a) and the NRA, however, isn’t just that they had some initial psychological impact, but, to repeat, “that Section 7(a) played a major role in boosting and shaping the era’s labor insurgency” (emphasis added)33This is a far bigger proposition than saying that 7(a) inspired some workers, many of whom were already in motion, to strike or organize when it first became law. Even if we give 7(a) some credit for this, along with the upturn in the economy and the workers’ own prior organization and experience, by mid-1933 neither 7(a) nor the NRA generally played a role in shaping the direction and forms of unionism of that moment, much less for the era.

By the time of the 1934 strikes, the beginnings of the move from craft to industrial unionism and the democratic and grassroots nature of most of the new emerging efforts to unionize were the work of the workers and their grassroots leaders themselves. All of the Left-led strikes of 1934 had this industrial rather than craft character. There was nothing in the law or government policy of the early New Deal to encourage these outcomes. All of this took place before the major New Deal legislation of 1935 that produced Social Security, the Works Progress Administration, the NLRA, and more stringent industry regulation.

Electoral reality: pre-1936

The whole point of Blanc’s exercise is to convince us that electoral politics via the Democratic Party are necessary to the success of any worker upsurge, including presumably the uptick in organizing now going on in the United States, and even for “working-class politics.” Putting aside Blanc’s overly rosy picture of the New Deal, this idea has little basis in reality. Beyond primitive lobbying or the involvement of some unions in local politics, electoral action via the Democratic Party by organized labor or the Left at that time was inconsequential prior to 1936.

In 1932 organized labor was weak, politically divided, and devoid of an electoral strategy or organization. As Blanc notes, neither the AFL nor the Mine Workers even endorsed Roosevelt. At the same time, the Amalgamated Clothing Workers and the International Ladies Garment Workers backed Norman Thomas, the Socialist Party candidate. The Communist and Socialist Parties both ran independent campaigns in opposition to the two major parties. Disgust with the Republicans by the 1932 election certainly gave the Democrats a big majority in Congress, as well as the presidency. As historian Irving Bernstein wrote in his account of the 1932 election, however, “The labor unions as organizations made virtually no contribution to Roosevelt’s victory.” As a consequence, “Roosevelt owed the labor movement nothing for his victory.”34

The capitalist politicians who carried the National Industrial Recovery Act through Congress in 1933 were a coalition of urban machine operatives, Dixiecrats, liberals, mostly from the Northeast like the Tammany Hall Democrat Robert Wagner, or patrician reformers like Roosevelt in legislative alliance with a significant number of liberal Republicans. Roosevelt and the Democrats won the Eastern and Southern European “ethnic” (mostly Catholic) urban working-class vote. However, that vote was not organized or delivered by the weak and politically insular AFL unions, the garment unions, conservative railroad brotherhoods, or even the more aggressive miners, who were, in any case, not urban-based, much less led by the political Left. It is not tenable to argue or imply that 7(a) or the early New Deal generally were in any way an example of effective organized electoral action by labor or the Left. They were largely the result of the response of politicians to both the Depression itself and the rising social discontent of the previous three years (see below). Nor did electoral action play a role in the mass strikes of the early New Deal or the movement toward industrial unionism.

The rise of the Democrats first in Congress and then to the presidency, which led to the political realignment that emerged in 1932, was largely the result of a demographic shift long in the making. By the 1920s much of the population moved from farm to city and, as political scientist Samuel Lubell emphasized, millions of the children of immigrants came of voting age, which made the urban white “ethnic” working-class vote a major factor in elections. It was this process that made the Democrats a majority party and reinforced the Democratic state and local parties and machines over this period as they expanded their “ethnic” base beyond the Irish. In the 1928 presidential election Democrat Al Smith, who was Catholic, won the urban vote for the Democrats for the first time, while more non-Southern Democrats were sent to Congress—a precursor of 1932. While the 1920s were the heyday of the old machines, the New Deal presented some new opportunities in terms of federal relief and jobs for these and newer urban machines with a now broader base as Roosevelt sought to increase and sustain his majority.35Organized labor, on the other hand, was weak and depleted.

Roosevelt won by a large majority in 1932, but with a low voter turnout of 52.6 percent. This was, nevertheless, accompanied by huge gains for the Democrats in Congress in 1932 (97 more in the House and 12 in the Senate) in reaction to the depression and Republican policies. This was followed by more gains in 1934 (six more in the House and ten in the Senate). The Democrats’ gains in 1934 were unusual for a midterm election, when the president’s party typically loses seats in Congress. No doubt the 1934 election was in part a referendum on Roosevelt, but as one of the few full-length studies of midterm elections put it, the 1934 election was seen as “not just an endorsement of Roosevelt but as a plea for even greater reformism.”36This, in turn, reinforces Goldfield’s assessment, cited by Blanc, that the results of the 1934 midterm election were “in good part reflected in the Depression-inspired demands and attitudes of the vast majority of the population.” 37

The idea that Roosevelt was leading a pro-labor crusade is far from reality. Prior to 1936, the working-class vote came through traditional channels. As a leading study of urban machines put it, rather than being some left-pro-labor crusade,

“Roosevelt’s patronage treatment of the big-city Irish bosses demonstrated his reluctance to promote an ideological revolution within the Democratic Party. Rather than a long-term strategy of turning the states into New Deal bastions, FDR was more interested in short-term electoral results.”38

James MacGregor Burns, one of Roosevelt’s major biographers, was even more explicit: “He did not conceive of himself as the leader of a majority on the Left, as a party leader building a new alignment of political power.” Rather he was a “political broker” whose goals “could be achieved by coaxing and conciliating leaders of major interest groups into a great national partnership.” Thus, “the politics of broker leadership brought short-term political gains at the expense, perhaps, of long-term advances.”39Beginning in 1935, the allocation of WPA jobs via selected urban machines would become key in further building his majority in 1936. Only later, as opposition to the New Deal grew after the 1936 election, even among Democrats, would FDR attempt to combat his internal conservative opposition—and with little success.

In 1934, the Left and at least a significant sector of union activists still pursued independent political action. The Socialist and Communist parties still ran candidates against the major parties. The leftist leaders of the militant strikes of 1934 did not support Democrats, much less mobilize their members to do so. The garment unions had not yet converted to the Democrats. The Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), as a committee inside the AFL, was not formed until the fall of 1935. Indeed, despite all the strikes and the moves toward industrial unionism in 1934, none of the major new industrial unions had yet been formed, organized labor as a whole was fragmented, and union membership, though it grew that year, was still below that of the mid-1920s and scarcely above that of 1932. Roosevelt, in turn, showed little interest in courting the unions or advancing unionism in 1934. On the contrary, as we have seen, his interest was in creating stability in part by curbing the strike movement via the NRA and its labor boards and industry codes.40

With a recovery in 1934, the number of strikes and strikers nevertheless exploded by spring of that year and increased again in the spring of 1935, undermining the whole NRA edifice in practice. Despite the efforts of the labor boards, the administration had no workable means of stemming the tide of rebellion or addressing the growing demand for further reforms in the face of the deepening social crisis. Then, on “Black Monday,” May 27, 1935, the Supreme Court ruled the NIRA unconstitutional. This left the government with no labor policy at all in the face of rising strike activity by May and, more importantly, no framework for sustaining the recovery. The strike wave, the increased role of radicals, and this crisis—more than the positive election results or the enthusiasm of a few New Deal “brain trusters”—forced the administration and Congress to act and address the growing demands for more radical measures. Roosevelt halted the adjournment of Congress and began what is known as the Second New Deal or Second Hundred Days, which went far beyond the first two years of his administration, creating Social Security and the WPA, as well as new permanent industry regulations, and, learning from the weaknesses of the NIRA, establishing the Wagner Act, which was signed into law in July 1935.41

Electoral reality: 1936 and beyond

The 1936 election was the first in which the CIO unions played a significant role—only after most of the New Deal legislation we are familiar with had already been passed. In April 1936, the CIO leadership formed Labor’s Non-Partisan League (LNPL), specifically to mobilize the union vote for Roosevelt, backed mostly by the CIO unions and funded primarily by the United Mine Workers. One aspect of the new LNPL was, as Art Preis put it, “to be a bridge back from independent political action for hundreds of thousands of unionists who then customarily voted Socialist or Communist or were clamoring at the time for a labor party.”42As we will see below, despite Blanc’s effort to dismiss it, there was in fact a widespread movement for a labor party in 1935–36. The LNPL even created the American Labor Party in New York State to capture the garment workers’ traditional Socialist vote, as Bernstein also noted.43

While the LNPL represented the first such national electoral mobilization by unions and contributed to the majority won by Roosevelt and the further gains by Democrats in Congress, most of the newer industrial unions were still numerically and organizationally weak at the time of the November 1936 election. In fact, voter turnout was not particularly high at 56.9 percent. As Robert Zieger pointed out in his history of the CIO, “In an election in which Roosevelt captured 60 percent of the two-party vote and 523 electoral votes, even labor’s contribution could hardly have been decisive.”44Roosevelt could count.

Then, beginning in early 1937, the situation changed radically as strikes exploded and union membership took its biggest leap in the decade from 4,164,000 in 1936 to 7,218,000.45This “giant step” was not a result of the NLRA being declared constitutional in May 1937 or of the NLRB in general, as Blanc implies when he writes that “[t]he new pro-labor National Labor Relations Board played a pivotal role in aiding workers’ militant unionization efforts.”46In fact, nearly two-thirds of the 1,860,621 million workers who struck altogether in 1937 did so between January and May, before the NLRA had any legitimacy or conducted a significant number of elections.47Furthermore, of the just over 3 million new union members in 1937, only 389,657 workers, or 13 percent, voted in an NLRB representation election in that year, compared to the 1.2 million who struck for recognition.48In addition, countless other workers benefited from those strikes, such as those who won voluntary recognition at U.S. Steel in the wake of the General Motors sit-down strike, when U.S. Steel boss Myron Taylor, aware of the turbulent United Auto Workers (UAW) victory and in the face of a growing Steel Workers’ Organizing Committee’s drive, calculated that a company victory over a strike would not be worth the “terrible cost in lives, in ill-will, in business, and in property,” as Bernstein reported.49

The limits to which the new NLRB aided worker organization were dramatically demonstrated in the 1937 Textile Workers’ Organizing Committee (TWOC) drive to organize southern textile workers. The hope of employer cooperation and reliance on the “pro-labor” NLRB and its elections pushed by New Deal enthusiast and TWOC chief Sidney Hillman rather than worker action and militancy in the crucial 1937 drive led to defeat in southern textiles as mill owners ignored or resisted NLRB rulings, the NLRB processes and court challenges dragged out, and the federal government took no direct action on behalf of the workers. As one of the major historians of the TWOC campaign put it, “The TWOC campaign in southern cotton textiles in 1937 and after and its use of the Wagner Act dramatically demonstrated that federal legislation was not a substitute for union power and that legislation by itself did nothing to create union power.”50By 1939, a mere seven percent of the South’s 350,000 cotton mill workers had been organized.

It was above all the victory of the General Motors sit-down strikers in February 1937 that sparked the upsurge of strikes from March through May 1937 and, in turn, led to rapid union growth. The UAW sit-down strikers at GM in Flint, Michigan, who initiated this upsurge rejected the use of the NLRB out of hand—both because they were certain GM would ignore NLRB rulings and because they were unsure they could win an election. They chose direct action in the form of sit-down strikes (plant occupations) to galvanize the workforce instead. As a result, UAW membership grew from 88,000 in February to 254,000 by April, before the NLRA was declared constitutional, and without resort to the NLRB. After GM recognized the UAW in February, the number of workers initiating strikes in all industries rose from 99,335 in February to 290,324 in March, 321,572 in April, and 325,499 in May, after which the number of strikers declined. The number of sit-down strikers rose from 31,236 in February to 167,210 in March–all before the NLRA was declared constitutional or a significant number of workers took advantage of its election procedures.51

Furthermore, the whole post-reelection FDR/New Deal/CIO honeymoon didn’t last long. In June 1937, only three months after the beginning of his second term and about four after the UAW-GM settlement, Roosevelt, exasperated by the intransigence (class struggle) of both sides in the “Little Steel” strikes, but apparently unmoved by the sea of blood the employers and their police had unleashed on the strikers, publicly declared, “A plague on both your houses.”52This was a particularly sharp slap in the face to labor, since the CIO leaders had mobilized voters for Roosevelt in the steel towns. As Zieger writes, from the point of view of the CIO leaders, “The election victory permitted the CIO to redirect its attention to the steel campaign,” only to have FDR denounce the union as well as the steel companies.53

In August, an even more tangible assault on the working-class took hold when FDR began drastically cutting relief and job programs to reduce the federal deficit and plunged the economy into “The Roosevelt Recession.”54Successful organizing all but ground to a halt, while NLRB representation elections that were supposed to aid “workers’ militant unionization efforts” slowed to a crawl, with 282,470 workers casting ballots in those elections “won by some form of labor organization” from July 1937 to June 1938 (the NLRB’s fiscal year), declining to 138,032 from July 1938 to June 1939. 55By 1938, CIO membership stagnated and then actually fell by 1940, even before the mineworkers pulled out in 1941, and despite an uptick in the economy.56

With the CIO bureaucracy locked into the Democratic coalition and administration with the support of the Communist Party and its union leaders, and the economy in recession, it would take the wartime recovery to boost union membership significantly. The major policy “reward” for labor’s electoral support in 1936 was a slap in the face and the economic consequences of the “Roosevelt Recession,” which were a great deal more than “psychological.” Just what positive political lesson are we supposed to draw from this dismal picture?

How working-class rebellion took shape

The long-term upsurge in strikes and organization that took a sharp turn in mid-1933 and lasted, with ups and downs through mid-1937, did not appear magically out of nowhere. Like all such spikes in the class struggle, it had a pre-history that made it possible. Prior to Roosevelt’s election in 1932 and the early New Deal, many of the first signs of working-class rebellion and organization in response to the Great Depression took the form of increased disruptive developments, such as unemployed organizations that grew to 350,000 to 400,000 members, their mass demonstrations, grocery store “mob lootings,” forced eviction reversals, hunger marches, farmers’ “strikes” and “holidays,” the veterans’ “Bonus March,” and, as we will see below, strikes. The radical-led unemployed organizations not only provided support for strikes in the early and mid-1930s, but also directly built the militant minority when unemployed activists returned to work as the economy picked up.57

These sometimes violent and frequently disruptive forms of workers’ struggle against the desperate conditions of unemployment, housing evictions, inadequate public relief, and employer speed-up and wage-cutting of the early Great Depression provided accumulated experience, leadership, and development within the working-class, much of it led by radical organizations that would also play key roles in the rise of industrial unionism.58That is the process of rebuilding the internal grassroots networks, organization, and leadership of the class that had been largely destroyed in the wake of the defeat of the 1919–22 strike wave, the “Red Scares” that accompanied this and the recurrent recessions of the 1920s.

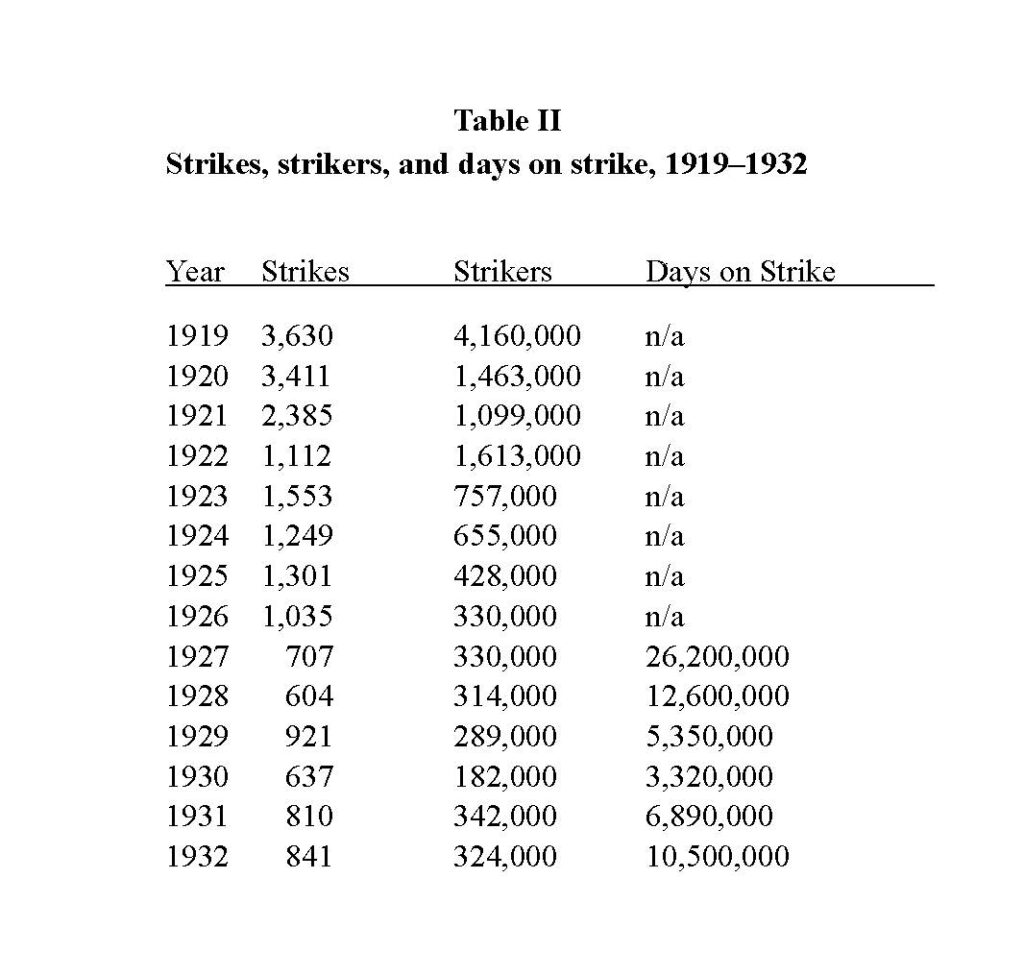

As the Washington Star reported of the class nature of the veterans’ bonus marchers who were sweeping across the country in the spring of 1932, seizing trains and disrupting daily life in one city after another, “They are truck drivers and blacksmiths, steel workers and coal miners, stenographers and common laborers. They are black and white.”59And, as we also know, many of these various pre-New Deal actions, events, and organizations were led by political leftists and organizations. In short, this was worker self-activity, providing organized experience and the beginnings of the formation of a militant minority based partly among communists and socialists of various types with experience in these early organized struggles. Even at the depth of the Depression in 1931–32, strike activity resumed an upward trend after falling by every measure from 1923 to 1930. Blanc fails to see the continuity in these earlier movements and the rise of strikes.

Table II shows the decline and rise of strikes, strikers, and (where statistics are available) days on strike from the post–World War I upsurge in 1919 through 1932, prior to the business and strike upswing in 1933. It was undoubtedly this huge 1919–22 strike wave—described in of the major Brookings’ study of the NRA as “the greatest industrial battle witnessed in American history”—that the authors had in mind when they wrote that no “machinery for handling labor disputes” was initially included in the NIRA by its drafters because, to them, as Blanc cites, “acute labor strife … seemed remote.” The authors of the report also wrote off such an upsurge because they thought “labor would have little to strike for, since the codes would fix maximum hours and minimum wages, abolish child labor, and improve working conditions generally.”60They could hardly have been more wrong on both counts.

After the number of strikes and strikers hit their low point in 1930, at the depth of the Depression and prior to the New Deal, the number of strikers rose again, approaching the level of the mid-1920s under the worst economic and political conditions of the era. The number of days on strike rose much faster, suggesting that the strikes of this period were prolonged and often lost. Many were in opposition to wage cuts and speed-up. Nevertheless, a few hundred thousand workers, sometimes led by leftists, dared to defy their bosses and gained experience in collective action in the form of strikes, many in industries that would figure in the next upswing in struggle. Notable among these strikers were the coal miners, who would play a key role in the future of industrial unionism and whose wildcat and often Communist- or radical-led strikes swept across Kentucky and West Virginia, the central competitive coalfields, and Pennsylvania in 1931 and 1932.61All of these developments came prior to the election of Roosevelt, the early New Deal, and Section 7(a) of the NIRA, which commonly receive so much credit for the upsurge of the second half of 1933.

There are, of course, no statistics on the development of a “militant minority” or its politically left-wing core. But we can get a rough idea of the growth of this radical core from that of the working-class-oriented Left of the era. According to figures compiled by Goldfield, the Communist Party, which played a central role in all the developments from 1930 through the upsurge of 1936–37, grew from 7,500 members in 1930 to 24,500 in 1934, by the time of the major strikes, and then to some 42,000 or so in 1936, at the beginning of the major upsurge that led to the growth of the CIO. 62The Socialist Party grew from an estimated 9,840 in 1930 to about 19,000 in 1935.63Its members played leading roles in the early strikes and organization in auto and shipyards, as well as the older established needle trades.

The smaller Trotskyist Communist League of America and the Musteite American Workers Party, both of which formed in this period, played key roles in a number of strikes from at least early 1933.64Members of all these groups had also been active in the early organization of the unemployed and other community-based struggles mentioned above. It was often these various radicals who provided the links between the earlier forms of struggle and the strike wave that began in 1933.

In other words, by the time of the mid-1933 upturn in strikes Blanc attributes to 7(a), there were already hundreds of thousands of workers with organizing experience and a sizable political core to the militant minority participating in an increase in strikes and organizing. It were these developments, above all, that laid the groundwork for the worker upsurge of the New Deal era and made it the giant, if partial, step forward, mainly in the form of the CIO.

The inevitability of hindsight vs. the imperative of political choices

In his fourth installment, Blanc goes further still in “proving” that the possibility of a mass socialist movement, a labor party, or any type of new independent Left political action or organization in the New Deal era was zero. In a fact-filled narrative, Blanc argues that whatever sentiment there might have been for independent political action, it simply did not (and could not) take hold. Perhaps inadvertently, he also shows that all the efforts by the insurgent CIO unions through semi-independent “party surrogate” type organizations in several states failed to dislodge the Democratic conservative “regulars” or move the Democratic Party to the left. Not even the belated efforts of Roosevelt himself—the most powerful president to date and the pioneer of the modern federal executive and “imperial presidency,” who used his huge Congressional majority to bring the Supreme Court to heel—could defeat his own party’s conservative wing in party primaries or undo their growing alliance with right-wing Republicans.65

The culprit of all this political inertia, it seems to Blanc, was not the Democrats themselves or even organized capital, but the “political system,” public opinion, and the electorate. Poll after poll at the time, Blanc reveals, showed the public didn’t like strikes or industrial unions, while the ultimate poll, the first-past-the-post election system from primary to president, supposedly showed the urban working-class masses to be solid regular Democrats to the end—even though only a little more than half of all those eligible to vote did so in presidential elections and less than half in the midterms. In short, Blanc has argued that nothing other than what happened, just as it happened, was possible. Or to put it another way, what did happen was inevitable.

On the question of a labor party, which you would expect him to be sympathetic to, Blanc quotes Eric Davin’s conclusion, “There were and are almost insurmountable cultural, psychological, and structural obstacles built into the U.S. political system that argue against the success of any third party—labor or otherwise.” This generic assessment would seem to preclude independent working-class politics as much today as back then. But, even aside from the modifier “almost,” Davin goes on in the next sentence to say, “Still, in the face of these systemic hurdles, in the mid-thirties major sections of both the leadership and rank and file of organized labor struggled to fulfill the ancient dream of a labor party.”66Confronting “systemic hurdles,” after all, is what socialists do.

Davin’s study, in fact, reveals a nationwide movement for a labor party based in “major sections” of organized labor in the wake of the huge strike wave of 1934. As he notes, “Every major center of industrial unrest in 1934, from Toledo to San Francisco, witnessed labor party activity in 1935.” According to an earlier study by Davin with Staughton Lynd, twenty-three cities actually saw labor parties launched and candidates fielded, with some winning office, while ten central labor councils in other cities voted in favor of one. So did the state labor federations of Wisconsin, Rhode Island, Connecticut, Vermont, and New Jersey. Their case study of Berlin, New Hampshire, shows that the labor party there elected city councilors and/or mayors into the early 1940s. By 1936, the labor party movement spread to at least 22 states, with varying degrees of strength. Most of the major industrial unions except the miners voted for a labor party at their conventions in 1935, while at that year’s AFL convention, the Textile Workers’ resolution for a labor party lost by a narrow delegate vote of 104 to 108, though the opposing delegates represented the larger older unions and potentially more roll call votes. At its 1936 convention the United Mine Workers’ delegates, in defiance of John Lewis, passed a labor party resolution. So did those at the UAW convention that year—although Lewis browbeat the UAW delegates into also endorsing Roosevelt.67There was, in other words, an independent class-based political dynamic taking shape as class conflict intensified.

Furthermore, Davin argues that at that time, “The loyalty of organized labor and the new urban working-class voter to FDR and the Democrats was therefore not a foregone conclusion and had to be won after intense, continuing, and delicate internal struggle.”68That the leaders of the CIO recognized this problem is clear from the nature of the way in which they sought to win the workers’ loyalty to FDR and the Democrats and thwart the labor party movement through the formation of Labor’s Non-Partisan League (LNPL) in April 1936. It was, as Davin argues, this labor party activity that encouraged the specific formation of an organization like the LNPL and why “top CIO leaders were so deliberately vague about the eventual political trajectory of Labor’s Non-Partisan League—into putative independent political action along the lines of New York’s American Labor Party or into an enduring alliance with the Democratic Party.”69Even the Minneapolis Trotskyists and Leon Trotsky himself expressed confusion as to what LNPL represented and how to relate to it as late as 1938.70

Given the political direction and outcome of LNPL and its bureaucratic nature, it is hard to see why this would be a model for today. In any case, wouldn’t it have been the political imperative of the socialists of that time, who did not have the benefit of hindsight, to fight for the loyalty of the workers to independent working-class politics even in the limited form of a labor party? There was, after all, a sizable movement for such politics and an intense political struggle over this question. For the socialist activist in 1935–36, it was a matter of “Which side are you on?” in that internal struggle.

Yes, in retrospect, it all happened the way it happened and the gains made by the working class were what they were and no more. But history and class struggle are full of contradiction and contingency, as well as both obstacles and openings at various times. As Mike Davis put it elegantly in terms of assessing the “CIO’s conflicting possibilities and determinancies,” one has to focus on the “tension between the received conditions of its emergence and the new terrains opened up by the creative impudence of struggle.”71Furthermore, the working class is not a single mass that moves neatly in unison. Some groups are more deeply affected by material and political conditions, some move before others, some have more leverage, pulling or pushing broader groups into motion, some never move. How to approach this reality involves analysis, debate, conflict, organizations, strategy and tactics. For socialists, politics includes the science and art of finding and using every opening in the changing situation and fluctuations of consciousness, even of a minority, to advance the organization, power, and consciousness of the working class. All those who fight for social change inevitably face complex forces and barriers and a future they cannot predict. We can and must analyze the various political and economic trends and counter trends, balance of class forces, and conditions, but we can never be sure the course of action we propose will succeed. The alternative to action, however, is paralysis and surrender to the status quo.

What lesson are we supposed to draw from the fact that the majority of the public didn’t like strikes or industrial unions—who, in fact, according to those polls Blanc cites, preferred craft unions? Obviously, Blanc would not argue that those socialists and workers who fought for industrial unionism in 1934 shouldn’t have done so because majority opinion was against them. Change always starts with the views and actions of a minority. Millions of workers in the 1930s won new industrial unions but failed either to create an independent working-class party or to move the Democratic Party and the Roosevelt administration to the left, or even to prevent its move to the right after 1936. So, it is hard to tell just what political lessons we are to draw from Blanc’s rethinking of the New Deal. Go with the flow?

In a different vein, Blanc seems to offer us some contemporary political choices: “Pro-union Democratic politics is better than neoliberal centrism or Republicanism, but independent working-class politics is far better still.” 72Actually, “independent working-class politics” and organization aren’t simply “far better.” They are fundamentally different in their class content, political independence, democratic organization, grassroots base, and orientation toward increasing working-class power and undermining and eventually eliminating capitalist power. There can be a range and variety of working-class policies, but there isn’t some conventional poli-sci continuum from right to left along which to choose working-class politics. We can’t simply work our way incrementally from the merely “better” liberal capitalist politics to the “far better” working-class politics. There are class lines. Ruptures to be made. The choice is a qualitative one.

Since the qualitative choice of working-class politics appears (too?) difficult today, Blanc opts for the “better” one of “Pro-union Democratic politics.” Yet, whatever one thinks the reasons for this were, it was precisely the submergence of the rising labor movement of the mid-1930s into the “better” New Deal Democratic Party that was forged in 1936 and deepened thereafter that explains why there is, as Blanc reminds us, an “absence of a mass working-class politics” in the United States. This situation didn’t come out of nowhere. It involved political choices, organization, and struggle—not the tyranny of public opinion or some inevitable outcomes of the U.S. political system that left organized labor and the working-class in the United States as a junior partner (soon turned poor relative) without a political force of its own.

It was the collective political choice by the industrial union leaders to draw their members into electoral politics in an organized manner–via a party of capital that had no membership and no democratic structures through which to affect its policies–that set the course for which the U.S. working-class has paid dearly ever since. Despite the fact that, measured by political outcomes, it was not very successful, it has been a choice that the majority of union leaders and even many on the Left have made over and over and that too many seem determined to make again. Yes, in retrospect, it seems “almost” certain those union leaders were going to win that fight, given the small size and divisions within (and defections from) the Left, the loyalty many members felt to their union once the decision was made, the ideology and increasingly top-down practice of the CIO leadership, and the widespread but by no means universal popularity of FDR and the major Second New Deal reforms. But which side would Blanc have been on?

It was also this electoral “alliance” and the governments it produced that contributed to or furthered the bureaucratization of the major new unions beginning in the late 1930s and throughout the Second World War, in particular, well before McCarthyism or the Cold War.73That, too, was a struggle in which the top leaders had the advantage but in which socialists had to choose sides—and not all chose the right one. Since then, it is the same dependent electoral “strategy” that has enabled the long decline of the unions in the face of employer opposition. It is this mainstream electoral politicking that, along with the inequality within the working class and continuous disorienting changes in the economy, has aided the dilution of class consciousness, encouraged the illusion of “middle-class” status, and made it impossible for union leaders to prevent huge numbers of their own members from voting Republican (including for Donald Trump).

In other words, this version of electoralism has been a major factor in depoliticizing the working class in the United States. Yet, in the name of something “better” and the alleged impossibility of anything else, we are once again urged to follow this well-trodden, bankrupt electoral path to political class subordination. Who was it who quoted Mark Twain as saying, “History never repeats itself, but it does often rhyme”?74

We want to hear what you think. Contact us at editors@tempestmag.org. And if you've enjoyed what you've read, please consider donating to support our work:

DonateKim Moody View All

Kim Moody was a founder of Labor Notes and the author of several books on US labor. He is currently a Visiting Scholar at the Centre for the Study of the Production of the Built Environment of the University of Westminster in London, and a member of the National Union of Journalists. He is the author of many books, including On New Terrain: How Capital is Reshaping the Battleground of Class War, In Solidarity: Essays on Working-Class Organization and Strategy in the United States, and Tramps & Trade Union Travelers: Internal Migration and Organized Labor in Gilded Age America, 1870-1900.