“People have to act collectively”

Resisting the new McCarthyism

Tempest Collective: Your book Many Are the Crimes: McCarthyism in America presents a rich and detailed history of the impact of McCarthyism on the Left and on U.S. society more broadly. We’d love to talk to you today about some of the lessons we can draw from this history in seeking to understand what some have called the “new McCarthyism” today. But first I wonder if you could speak to the tension in the term “McCarthyism” itself. McCarthyism was never about one individual but a much broader set of institutional forces. Could you discuss how you understand the conditions that gave rise to what we call McCarthyism? Do you think we have entered or are entering a period that we can meaningfully understand through the lens of McCarthyism? If so, how? Or if not, where do you think the analogy falls short?

Ellen Schrecker: The comparison to what’s happening today is apt—because McCarthyism was not about one person. And what’s happening today within our society and the erosion of democratic practices and values is not just about Donald Trump.

And we have to keep that in our heads at all times. We’re fighting a worldwide phenomenon—and it’s absolutely terrifying. It’s so much worse today. I am so much more frightened now. And I lived through McCarthyism.

I grew up in the 1950s. Everything was shoved under the rug. My sixth-grade teacher was fired because he had once been a member of the Communist Party. But what we’re seeing today is worse because it’s dominating the mainstream.

Joe McCarthy hopped onto a bandwagon that was already playing at full amplification in the spring of 1950. The anticommunist Red Scare, which probably is the best term for the phenomenon we call McCarthyism, really began in the late 1940s. Anticommunism existed ever since the Communist Party was founded in 1919, but it never dominated domestic politics until the late 1940s.

It was a product of the early years of the Cold War. The United States had emerged from World War II victorious and very wealthy. What triggered McCarthyism was the Republican Party’s defeat in the election of 1948. They had been running on their normal program, which was to get rid of the welfare state, and it turned out that the voters liked the welfare state. You know, they liked Social Security, the various programs helping farmers, helping unemployed workers. They liked those. Well, who wouldn’t? So, the right realized they couldn’t win political power by relying on opposition to the New Deal.

So, what did they do? They said, well, the New Deal has been run by Communists. And Communists, as we know, took over Eastern Europe—which happened. And they stole the secret of the bomb—which also happened.

This McCarthyist scenario provided an opportunity that was picked up by mainstream Republican politicians. It soon developed into a huge attack on anything that smacked of the Left. Every part of the government bought into it.

In Congress, for example, there were very clever, very ideological, and opportunistic politicians like Richard Nixon, who became a member of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and became palsy with [FBI Director] J. Edgar Hoover, who was feeding him information. Nixon got headlines and attention and made a career out of it that led to the White House. And Hoover became the eminence grise of the Cold War Red Scare—devising and often running most of the repressive measures that constituted McCarthyism.

Nixon’s ascent encouraged other politicians to think, “We can do that.” And Joe McCarthy comes along. McCarthy was able to get enormous amounts of press, enormous amounts of attention claiming without any evidence, “I have here in my hand a list of 205 [State Department employees] that were known to the Secretary of State as being members of the Communist Party and who nevertheless are still working and shaping the policy of the State Department.” What’s important to realize is there had been Communists in the State Department, but they were all kicked out when the Cold War started.

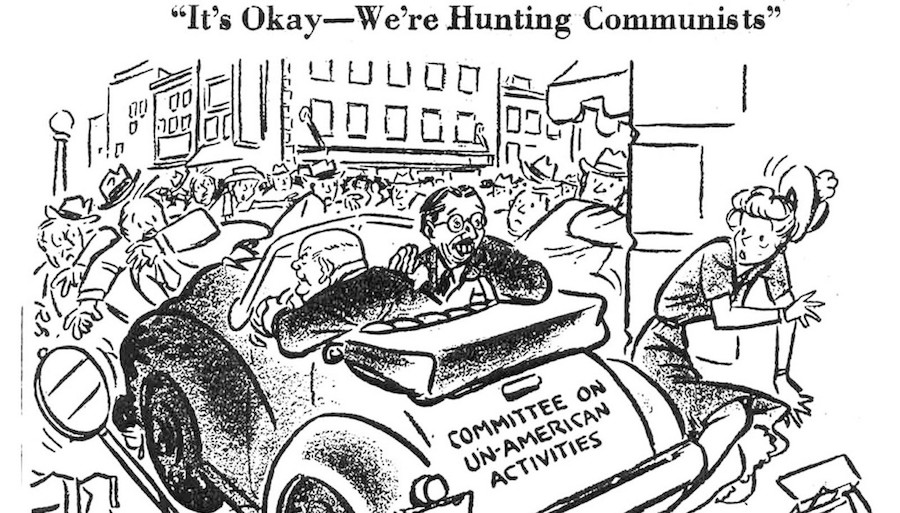

McCarthy was hardly the only conservative politician to ride the Red Scare for his own benefit, for his own career. But it got named “McCarthyism” after the word was invented by a cartoonist named Herblock, who did wonderful cartoons during this period making fun of the Cold War Red Scare for attacking a nonexistent enemy.

TC: In your book, you look at the impact of McCarthyism in many spheres, but in particular how it impacted the labor movement.

ES: Back in the days before McCarthyism, there was a very strong labor movement in the United States, which was always being attacked by the business community. They did not want to share their profits with the workers. They wanted to cut costs. They didn’t want to ensure that the workplace was safe for its workers because that might cut into their profits.

So, once the Republicans and other conservatives gained power, the main target of the Cold War anticommunist Red Scare became organized labor. In the United States, the labor movement has always attracted the far Left. Why? Because they’re Marxists. What do the Marxists want? They want the victory of the working class. So, they do what they can to help the working class gain power. They join unions. And they organize them effectively. They’re very good at that. As a result, Communists gained influence within the labor movement. The Republicans and their political allies knew that—as did non-Communists who were vying with the Reds for control over the labor movement— [and] who, along with conservative politicians and federal bureaucrats like Hoover, kicked the Communists out of the mainstream labor movement.

The labor movement was essentially defanged. Until very recently, it did not push for social justice issues like racial equity, but only for higher wages and benefits for its members. Above all, it stopped organizing and mobilizing its members—with the result that today we have a very enfeebled labor movement, and we have to build it back.

But it is being built back, which is just so heartening. My sister, who lives in Philadelphia, just sent me an article from the Philadelphia Inquirer. The faculty at the University of Pennsylvania had a huge demonstration to insist that the rich trustees are not going to tell us what to teach our students, because they don’t know a thing about chemistry, or about 17th-century history, or about slavery, and we’re not going to let them impose lies on our students.

TC: You have studied university-based movements, including in your latest books, The Lost Promise: American Universities in the 1960s and The Right to Learn. Clearly the right has undertaken a major offensive against academic freedom, affirmative action, diversity, equity, and inclusion programs, and other forms of antiracism, and faculty tenure protections. You also see now expression of solidarity with Palestine being repressed. Why is the right focusing so much of its energy here?

ES: That is such a good question that I’ve been trying to answer myself. Largely, I think, because universities are a pushover. They have long been one of the institutions that still harbors, protects, and even fosters criticism of the status quo.

We can look at what happened to universities during McCarthyism. And that’ll give us a little background for what’s happening today. You know, mainstream liberals have been accustomed to giving universities a free pass. Higher education helps democracy. It creates knowledge about the world we live in that’s important to have. But universities are no different from the rest of society. And, as many on the Left learned in the 1960s, they do not deserve the halo around them.

Those of us trying to protect American universities have to rethink the mission of higher education. We can’t just say it’s good in and of itself. We’ve got to be a lot more concrete, and we’ve got to fight back.

Right-wing business groups and philanthropists, people like the Koch Brothers, have been creating a sort of alternative university over the past 40 or 50 years by creating think tanks, subsidizing books and publications, using lawsuits, and gaining power within the judiciary.

But we can fight back. This didn’t happen in the age of McCarthyism. And I’m really thrilled at what is happening within the labor movement. I’m thrilled by what the United Autoworkers is doing—and they have thousands of members within the academy, as do the teachers unions, and the SEIU and other unions that have gone out and organized on campuses all over the United States, I’m thrilled with what the American Association of University Professors chapter at the University of Pennsylvania is doing. I’m thrilled by the fact that people are beginning to say that if we don’t fight back, we’re going to lose everything. And they’re winning.

TC: One of the ways McCarthyism works is through a chilling effect, encouraging self-censorship among people fearful of losing their jobs for lending the wrong book from their library, teaching the wrong lessons in their classroom, or attending a protest. What do you say to people who are understandably struggling with these fears?

ES: Everybody is afraid. Understandably. I’m not—because I’m retired. They’re not going to stop me from publishing or speaking out. What do I have to lose?

But people have to act collectively. You can’t just be an individual. We are not going to win if the only people who are fighting back are heroes.

The only way out of our mess is collective action—because in union, there is strength. Trying to be an individual hero is really reserved only for the bravest of the brave. Then they are people waving the flag on the barricades with nobody around them.

We don’t need heroes. My book about McCarthyism and the universities actually had a hero, Chandler Davis. By the way, he recently died. And his wife, a historian named Natalie Zemon Davis, also just died. She was amazing. One of the greatest historians of the 20th century.

Chan, as he was called, was a mathematician at the University of Michigan. When he was called up before HUAC in the spring of 1954, he decided he was not going to use the Fifth Amendment but the First Amendment to defend himself, hoping to challenge McCarthyism and provoke a critical judgment from the Supreme Court. But the court did not intervene in his case, so he went to prison for six months. He came out blacklisted completely. He had to go to Canada to get a job. In Canada, he helped take care of the young men crossing the border to avoid the draft during the war in Vietnam.

But we don’t need many more Chandler Davises. What we need is people who are willing to go to the demonstration because everybody else in their department is going to that demonstration. The only way forward is through collective action, is to work through faculty unions or through some ad hoc group that will organize on their campuses to roll back the attack on democratic teaching and learning.

I hope people are going to begin to recognize that this is what happened with the Vietnam War, which is an example of how collective action on the part of faculties changed history. If the faculties hadn’t begun the teach-ins that educated people about what was wrong with what the United States was doing in Vietnam right at the time, when Lyndon Johnson escalated the Vietnam war in 1965, there wouldn’t have been an antiwar movement by 1967 that, for example, made it impossible for members of the Johnson administration give talks at mainstream universities and that ultimately gained enough power to force an end to war. We don’t remember that.

So, today we have a similar educational task—among many others—of explaining that opposing bombing Gaza to smithereens is not antisemitism. It is just being critical of the foreign policy of a nation that is treating people in an inhumane and perhaps genocidal way. Do not close your eyes. Please open them and look at all the other people who have opened their eyes as well—and work together.

Featured image credit: Wikimedia Commons; modified by Tempest.

Opinions expressed in signed articles do not necessarily represent the views of the editors or the Tempest Collective. For more information, see “About Tempest Collective.”

Categories

We want to hear what you think. Contact us at editors@tempestmag.org. And if you've enjoyed what you've read, please consider donating to support our work:

DonateEllen Schrecker View All

Ellen Schrecker is a retired professor of history at Yeshiva University and the author of numerous books, including Many Are the Crimes: McCarthyism in America; No Ivory Tower: McCarthyism and the Universities; The Lost Soul of Higher Education: Corporatization, the Assault on Academic Freedom, and the End of the American University; and The Lost Promise: American Universities in the 1960s. Her current book, edited with Valerie C. Johnson and Jennifer Ruth, is The Right to Learn: Resisting the Right-Wing Attack on Academic Freedom.