The United States’ home-grown fascist

The antisemitic career of Father Coughlin

Driving around the metro Detroit area, whether for business or pleasure, I often pass by the Shrine of the Little Flower in Royal Oak, on 12 Mile and Woodward. The Shrine was infamously the home parish of Michigan’s second most prominent Nazi sympathizer, “Radio Priest” Charles Coughlin. The most prominent is still Henry Ford. Indeed, it would be difficult for anyone to be more pro-Nazi than the auto tycoon, recipient of the Nazi Grand Cross of the German Eagle, although Coughlin certainly tried.

Father Charles Coughlin served as parish priest of the Shrine from 1925-1966. The church gained early notoriety when Coughlin reported in 1926 that the Ku Klux Klan left a burning cross on church grounds. This would not be a fantastic occurrence. The Klan was very popular in Metro Detroit and almost succeeded in electing their candidate, Charles Bowles, as mayor in 1925. It was only due to thousands of disqualified write-in votes that Bowles lost. However, Coughlin biographer Donald Warren casts doubt on the cross-burning story. When he was writing Radio Priest: Charles Coughlin, The Father of Hate Radio, a collector of Coughlin memorabilia presented him with the alleged burned cross. It showed no signs of being even singed.

Regardless of the veracity of the story, it showed Coughlin’s talent for drumming up publicity. He made skillful use of media to get his message out. Beginning in 1926, Coughlin broadcast his Sunday sermons on the CBS radio network. The network then dropped him in 1931 when Coughlin began addressing controversial political topics during the worsening Great Depression. Coughlin’s show was picked up by the Detroit radio station WJR, which became the key station of Coughlin’s independent network. The network grew, claiming 26 stations by October 1932 and 58 by January 1938. Coughlin’s talks were mass media. It’s estimated that at the height of his popularity, a third of the country listened to his broadcasts. Hollywood offered to fictionalize his biography in the unmade film The Fighting Priest, with Coughlin playing himself.

Coughlin began as a staunch supporter of Franklin Roosevelt. He coined the phrases “Roosevelt or Ruin” and “The New Deal is Christ’s Deal.” Soon, Coughlin began to break with the President on issues like U.S. membership in the World Court, coining silver currency, and recognition of the Soviet Union. In 1934, he created his own political organization: The National Union for Social Justice. The National Union’s sixteen-point platform was inspired by the papal encyclicals Rerum novarum and Quadragesimo anno calling for government regulation of business, the right of workers to form unions, and a progressive income tax. Notably absent was any defense of civil liberties or a democratic government.

The National Union supported and was supported by various politicians. One of the biggest boosters was Cleveland Democrat Congressperson Martin L. Sweeney. Sweeney led a colorful life in office, including allegedly using his influence to protect his cousin Francis Sweeney, a prime suspect in the still unsolved Cleveland Torso Murders, and opposing the appointment of Jews to the federal bench. Other supporters included Representatives William Lemke, Thomas O’Malley, and William Connery plus Senators William Nye and Elmer Thomas, all of whom sent congratulatory letters to the 1935 National Union convention. Detroit area Coughlin supporters included former Detroit mayor Frank Murphy and Congressperson John Dingell Sr.

In light of Coughlin’s later explicit fascist sympathies, some of his pronouncements at this time take on a sinister tinge. When Coughlin gave his preference for “gentile silver” over gold, he was criticized for dabbling in antisemitism. Coughlin’s 1931 sermon “Prosperity” attacking the Treaty of Versailles was informed by information provided by Congressperson Louis T. McFadden, one of the earliest Congressional supporters of Adolf Hitler. During a Fall 1930 broadcast against communism, Coughlin despaired at “the anarchy, the atheism, and the treachery preached by the German Hebrew, Karl Marx.” He regularly attacked “international bankers,” often emphasizing their Jewish surnames. Despite this, Coughlin continued to find support from some Jewish leaders both in Detroit and nationally.

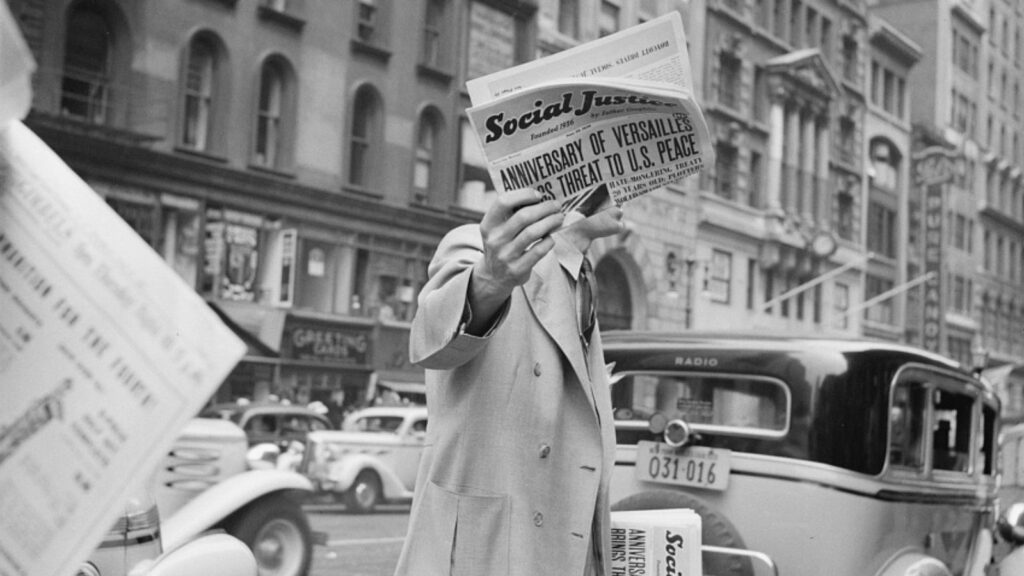

In 1936, Coughlin launched a full frontal assault on Roosevelt through the Union Party, an organization also supported by old age pension advocate Francis Townsend and Gerald L.K. Smith, who was in the process of devolving from the late Senator Huey Long’s lieutenant to “America’s No. 1 Fascist.” The three had difficulty collaborating, with Socialist Party presidential candidate Norman Thomas, deriding the Union Party as a creature of “two and a half rival messiahs.” The Party nominated North Dakota Congressperson William Lemke for President and former Boston district attorney Thomas O’Brien for Vice President. Their platform was essentially identical to the National Union of Social Justice platform. It was around this time that Coughlin launched the newspaper Social Justice as another avenue for his message.

During the 1936 election, Coughlin’s remarks about Roosevelt grew increasingly vituperative. At times it seemed like he and Smith were competing over who could hurl the most invective at the President. Smith exclaimed, “We’re going to get that cripple out of the White House!” At the Townsend Club Convention, Coughlin, not to be outdone, called Roosevelt a “betrayer“ and a “liar” and dubbed him “Franklin Double-crossing Roosevelt.” Even if Coughlin had been forced by clerical superiors to apologize for these remarks, he soon outdid them. At one rally he warned, “When an upstart dictator in the United States succeeds in making this a one-party form of government, when the ballot is useless, I shall have the courage to stand up and advocate the use of bullets.” At another, this one in Rhode Island, Coughlin promised “more bullet holes in the White House than you could count with an adding machine” if Roosevelt were to be reelected.

All this blood and thunder was for naught. Roosevelt won a landslide reelection and the Union Party got less than two percent of the vote. As small as this share was, it was still larger than that of the Socialist, Communist, and Socialist Labor Parties combined. The party failed to attract supporters of other electoral reformists such as the Wisconsin Progressive Party, the Minnesota Farmer-Labor Party, and End Poverty in California, who all backed Roosevelt. The reasons for the party’s failure are numerous. It wasn’t on the ballot in over a dozen states, the demagoguery of Smith and Coughlin likely repelled voters, and Lemke was a much less charismatic candidate than Roosevelt. Smith described Lemke, his own candidate, as “a complete composite of unattractiveness.”

During a Fall 1930 broadcast against communism, Coughlin despaired at “the anarchy, the atheism, and the treachery preached by the German Hebrew, Karl Marx.” He regularly attacked “international bankers,” often emphasizing their Jewish surnames. Despite this, Coughlin continued to find support from some Jewish leaders both in Detroit and nationally.

Although Coughlin promised to retire from broadcasting if Lemke received fewer than nine million votes, he was soon back on the air. His relationships with several groups changed when he returned. Previously, Coughlin had supported and received support from what could be termed the American labor aristocracy. AFL President William Green suggested sending a delegate to the National Union’s 1935 convention. James L. Ryan, president of a New York metalworkers union stated, “Father Coughlin is a messenger of God, donated to the American people for the purpose of rectifying the outrageous mistakes that have been made in the past.” Coughlin played a leading role in the Detroit-area Automotive Industrial Workers Association, one of several competing auto workers unions before the rise of the UAW.

Yet, Coughlin strongly attacked the growing CIO. He viewed it as Communist-dominated, saying in an interview that “the C.I.O. is pretty well contaminated with leaders who are Red in thought and action.” Social Justice preached that “Catholicism was as incompatible with the CIO as Catholicism was incompatible with Mohammedanism.” In The Shrine of the Silver Dollar, John L. Spivak reports both that Coughlin attempted to form a “company union” at Ford (the Workers Council for Social Justice) and that the priest offered a bribe to UAW president Homer Martin, on behalf of Ford, to split the CIO. In 1939, Coughlin attacked an International Ladies Garment Workers Union resolution to set up an anti-fascist defense guard.

Even more apparent than Coughlin’s shift on labor was his overt antisemitism. If Coughlin had any plausible deniability before, it was soon dispelled. In a radio broadcast after Kristallnacht, Coughlin minimized the Nazi persecution of Jews, saying “Jewish persecution only followed after Christians first were persecuted.” During the latter half of 1938, Social Justice reprinted the antisemitic forgery the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. At a 1938 speech in the Bronx Coughlin crowed “When we get through with the Jews in America, they’ll think the treatment they received in Germany was nothing.” The books sold in the Shrine reflected this as well. One of the titles was Rulers of Russia by Irish Priest Dennis Fahey, which Coughlin had the exclusive right to reprint. Fahey’s book explained that “The real forces behind Bolshevism in Russia are Jewish forces, and Bolshevism is really an instrument in the hands of the Jews for the establishment of their future Messianic kingdom.”

As early as 1936, sensing Lemke’s imminent defeat, Coughlin expressed sympathy for fascism: “Democracy is doomed. This is our last election. It is fascism or communism. We are at the crossroads-I take the road to fascism.” These sympathies continued throughout the rest of his time in public life. Like nearly all Catholic officials, Coughlin supported Franco’s forces in the Spanish Civil War, despite or even because of their reign of “White Terror.” In 1939, he proclaimed, “Practically all of the sixteen principles of Social Justice are being put into practice in [Fascist] Italy and [Nazi] Germany.”

It’s interesting to note that after Coughlin’s antisemitic and pro-Nazi utterances, federal elected officials continued to contribute articles to Social Justice. One was isolationist Senator William Borah. Borah’s anti-war feelings may have had a monetary source. When novelist Gore Vidal asked his grandfather, Senator Thomas P. Gore, about the source of several hundred thousand dollars found in Borah’s safety deposit box after his death, Gore said the money was from “[t]he Nazis. To keep us out of the war.” Another was Congressperson George Dondero, who actually had Coughlin as a constituent. Dondero served as Mayor of Royal Oak, Michigan for a spell and later defended the Nazi war criminals of I.G. Farben. The current Royal Oak Middle School used to be named after him. A third contributor was Minnesota Senator Ernest Lundeen, himself basically a Nazi propaganda agent.

Coughlin’s efforts also were championed by some from the world of arts. Architect Phillip Johnson went on to design the Museum of Modern Art in New York, but in the 1930s and 1940s, he was a reporter for Social Justice. Johnson joined the Wehrmacht in their invasion of Poland and described the burning of Warsaw as “stirring.” Poet Ezra Pound, a resident of fascist Italy, was another Coughlin supporter declaring, “Coughlin has the great gift of simplifying vital issues to a point where the populace can understand their main factor if not the technical detail.” Novelist Hillarie Belloc, a definite anti-Semite, was a contributor of articles to Social Justice.

The last organization Coughlin was affiliated with, after the demise of the National Union and the Union Party, was the clerical fascist Christian Front. The Front was particularly strong in New York and Boston. After Kristallnacht, New York’s WMCA refused to carry Coughlin’s program. Fronters picketed outside with signs saying “Buy Christian; vote Christian,” and “Send Jews back where they came from-in leaky boats.” In The Nation, James Weschler described the Front’s tactics for selling Social Justice in New York: “Throughout the week the salesmen are located at strategic, crowded points throughout the city, screaming antisemitic slogans…” Weschler described how Fronters assailed theaters that promoted the film Confessions of a Nazi Spy and how even children were conscripted to sell Social Justice. Boys were instructed to start crying that “A big Jew hit me!” to help drum up sales and sympathy.

The Christian Front was most infamous for the trial of the so-called “Brooklyn Boys,” seventeen men tried for attempting to overthrow the government. Although they were acquitted by a sympathetic jury, FBI files revealed that they were in possession of rifles pilfered from the National Guard and had engaged in military drilling for their planned coup. Frances Moran, head of the Boston Front was recruited as a German agent and the Boston Front continued its activities throughout World War II.

By this point, many who had earlier aided Coughlin were fed up. The National Association of Broadcasters, representing 428 radio stations, pulled the plug on his radio network in 1939. The next year, his voice could only be heard on two radio stations, and his ecclesiastical superiors ordered him to retire to the pulpit and cease his political activities. Social Justice continued to run with Coughlin’s assistance, although it was barred from the mail after Pearl Harbor due to its sympathy for Hitler and Mussolini. Coughlin’s shrill, hateful voice was finally silenced.

There were numerous questions raised as to whether Coughlin was being paid off by the Nazis during his career. He certainly had his share of foreign entanglements. Decorated General Smedley Butler, author of the classic pamphlet War is a Racket, passed along to the FBI that he received a phone call from Coughlin urging him to lead an army to overthrow Mexico’s government. Coughlin believed that the secular, nationalist regime of Lazaro Cardenas was pro-Communist and was persecuting Catholics. Coughlin wrote on several occasions to Benito Mussolini, offering Social Justice as a forum for the dictator. Warren’s biography does support the contention that Coughlin received funds from Germany, from the Foreign Office, the Detroit Consul, and other sources. It’s also true that Coughlin’s listeners were very generous in supporting his activities so how much of a difference Nazi funding made is unknown.

Although Coughlin was ordered to cease involvement in politics, the subject maintained his interest. Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater, an opponent of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, had a strong supporter og Coughlin when he ran for President as the Republican candidate in 1964. In his 1969 book Bishops Versus Pope, he inveighed against “loud-mouthed clerical advocates of arson, riot, and draft-card burning. They are swingers who suffer so terribly from an inferiority complex that they reach madly for the brass ring of popular recognition which dangles on the merry-go-round of secularism.” Readers might be surprised to learn that, per Coughlin biographer Sheldon Machus, the priest purchased $500 worth of Israeli bonds in 1955. The bonds were to prop up a nation he considered a bulwark against communism. This instance is further evidence that support for Israel can easily coincide with anti-Semitism.

Coughlin’s influence can be later seen in right-wing talk radio and somewhat in the careers of Protestant televangelists like Pat Robertson and Jerry Falwell. Even after his death in 1979, he remained a hero of the U.S. far right. Willis Carto of the antisemitic Liberty Lobby lauded Coughlin in his 1982 book Profiles in Populism. One of the clearest heirs to Coughlin is the Ferndale-based anti-LGBTQ hate group Church Militant. In a 2019 article, the group sang Coughlin’s praises as an opponent of the welfare state and Communism. They avoided the swastika-covered elephant in the room of Coughlin’s fascist sympathies. The group has also recommended Holocaust denier Nick Fuentes to members and gave a fawning interview to avowed Christian nationalist Georgia Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene. The conspiracism, xenophobia, and antisemitism of Coughlin can now all be found within Church Militant. In this sense, perhaps the Radio Priest never died after all.

Opinions expressed in signed articles do not necessarily represent the views of the editors or the Tempest Collective. For more information, see “About Tempest Collective.”

Featured image credit: Library of Congress; modified by Tempest.

Categories

We want to hear what you think. Contact us at editors@tempestmag.org. And if you've enjoyed what you've read, please consider donating to support our work:

DonateHank Kennedy View All

Hank Kennedy is a Detroit area socialist, educator, and longtime comic book fan.