Pat Robertson: Supervillain

Revisiting the X-Men’s God Loves, Man Kills

TTelevangelist Pat Robertson, who died in June, was a man with a strange assortment of friends and enemies. Among his friends was fellow televangelist Jerry Falwell, who blamed the 9/11 terrorist attacks on “the pagans, and the abortionists, and the feminists, and the gays and the lesbians”. Other friends were Liberian war criminal Charles Taylor and the dictator of Zaire Mobutu Sese Seko. His enemies included Hinduism, which he called “demonic”, Islam which he said was “satanic”, and Episcopalians, Methodists, and Presbyterians who were “the Spirit of the Antichrist.” Venezuelan Presidents Hugo Chavez and Nicolas Maduro were also in this category. Robertson called for both men to be killed.

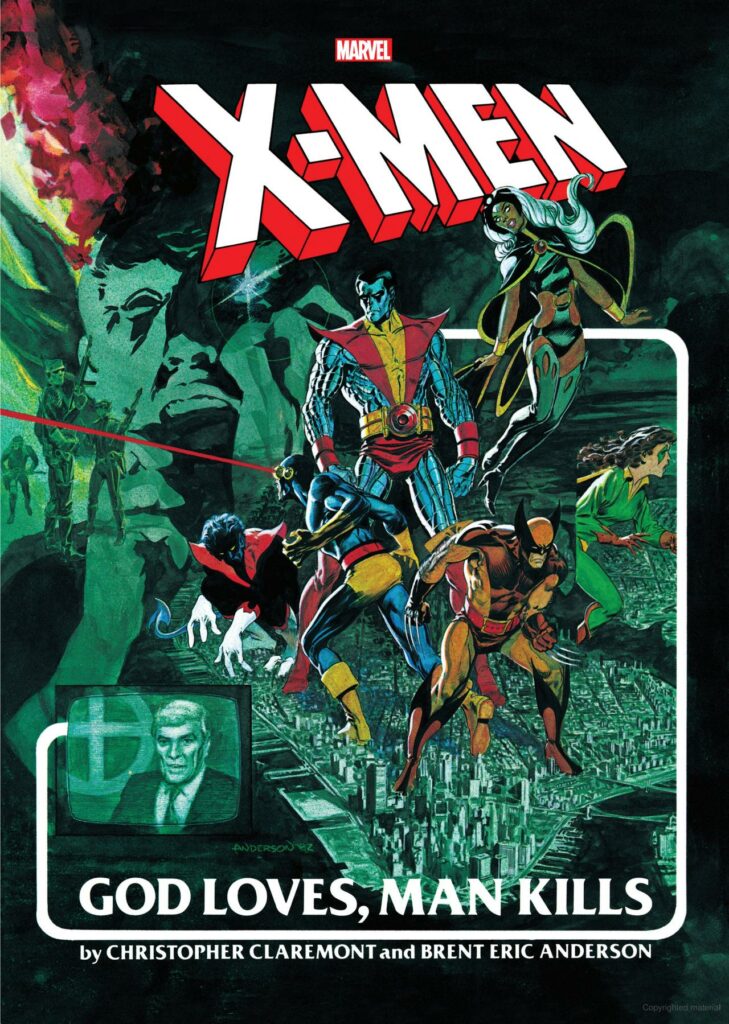

One lesser reported Robertson foe was Marvel Comics’ Children of the Atom, the Uncanny X-Men. From 1966 until his death, Robertson had run a daily television program called The 700 Club. A 1984 episode of the show focused on the current state of comic books. Among those discussed was Marvel Graphic Novel 5 (January 1983), featuring the X-Men story God Loves, Man Kills. The members of the mutant superhero team are repeatedly referred to as “subhumans” (keep this in mind). Robertson calls the story, which features a televangelist as the antagonist and religious imagery, “blasphemous.” To cap it off, Robertson and company falsely claimed that the price of the graphic novel ($5.95) was typical, although the average monthly comic in 1984 cost sixty cents. The implication is that not only are comic books corrupting children, but the publishers are getting rich off it to boot.

While Robertson’s comments mainly focused on the religious aspects of the comic book, it’s more probable that he was upset about the story’s deliberate political commentary. The late 1970s and early 1980s were a bonanza for televangelists like Robertson, Jerry Falwell, and the Christian Right. They had defeated the Equal Rights Amendment, gotten their man, Ronald Reagan, into the White House, and were eager to roll back the advances of the 1970s movements for gay and abortion rights. Hate groups were also on the march in Skokie, Illinois and Greensboro, North Carolina. Into this environment entered God Loves, Man Kills and its villain, televangelist Reverend William Stryker.

Earlier Marvel stories had addressed bigotry too. In the two-part story in Avengers 32–33 (September-October 1966), the superhero team battles a nativist, racist group called the Sons of the Serpent, obviously modeled after the KKK. However, when the story ends, it’s revealed that the Sons are led by General Chen, the head of a “hostile Oriental nation” (contextually, a stand-in for China). Chen wanted to use the Sons to sow division in America to make it easier to conquer. This is a reversal of the common segregationist argument that civil rights protestors were communist “outside agitators.” God Loves, Man Kills does not employ this plot. The bigotries of its villains are as American as apple pie.

X-Men writer Chris Claremont, who had a background in political science, described his parents as “young socialists in England” 1 and was influenced in writing the story by the deluge of televangelism and the dramatic potential in the conflict between Christian extremism and the X-Men. Artist Brent Anderson, who replaced Neal Adams, agreed with the political thrust of the story saying, “Sure, it’s possible to exclude politics from comic books, but not from art. Comics produced through avoidance of the real world are hardly satisfactory on any meaningful artistic level.”

God Loves, Man Kills begins with one of the most shocking and disturbing scenes in a mainstream superhero comic. Two children are hunted down and shot dead by a gang known as the Purifiers. The leader of the Purifiers tells them they are being murdered because they “have no right to live.” The children’s bodies are strung up in a playground with the slur “Mutie” scrawled on them in a scene visually referencing countless lynchings and hate crimes, especially given that the children are Black. Unsurprisingly, the cover of the comics lacks the seal of approval of the Comics Code Authority, which would forbid this kind of on-panel violence.

After some time X-Men’s enemy (and Holocaust survivor) Magneto retrieves the children’s bodies, where readers meet Reverend Stryker. Despite an uncanny similarity to former Vice President Mike Pence, the character was actually visually based on President Reagan’s Chief of Staff Alexander Haig, another right-wing political figure. It quickly becomes clear that the relationship between Stryker and the Purifiers is akin to that between Father Charles Coughlin and the Christian Front. He provides divine sanction to the violence that they carry out. Stryker’s speeches on mutants are very similar to what 1980s televangelists were saying about gay people and other groups. Take Jerry Falwell’s statement, “Gay folks would kill you just as soon as look at you.” Simply replace “gay” with “mutant” and it could be a Stryker quote.

Throughout the story, it is apparent to readers that Stryker’s views are not his alone. In one sequence, Kitty Pryde of the X-Men, gets in a fight with one of her classmates who supports Stryker’s crusade against mutants. Kitty’s classmate calls her a “mutie-lover,” unaware that Kitty is herself a mutant. When Kitty’s teacher Stevie Hunter, a Black woman, says that hateful words are just words, Kitty tearfully asks if she would feel the same about the term “n*****-lover.” Chastened, Stevie concludes that Kitty is right. Some have disagreed with Kitty Pryde’s, and by extension Chris Claremont’s, use of a racial slur to make the point that members of one oppressed group can be unsympathetic to members of another oppressed group. Recent prints and digital versions of the story have actually edited the word out, presumably to avoid controversy.

In 2020, Marvel Comics itself published the article “Solving For X: ‘God Loves, Man Kills’ Through the Lens of Now” by John Jennings, which addressed the issue of the use of the slur head-on. The article starts off on the wrong foot with an editor’s note saying, “The comics are products of their time, portraying the prejudices and discrimination that were commonplace in American society through an X-parable.” The reason that God Loves, Man Kills endures is not because it is a “product of its time” but because its anti-bigotry message is timeless. Furthermore, to regard the prejudices allegorized by the story as products of the past is simply wrong. Homophobia, transphobia, racism, anti-Semitism, and other forms of bigotry still need to be fought against today. Cynically, I wonder whether the note has anything to do with then-Marvel CEO Ike Perlmutter being a Donald Trump confidant. When Art Spiegelman referred to the former President as the “Orange Skull” in an essay meant for a reprint of Golden Age Marvel stories, he found that it was refused publication.

Jennings makes the point that Kitty Pryde is white and that while she is a mutant, she can “pass” as a human. She does not have the fangs, tail, and blue fur of her teammate, Nightcrawler, who is instantly recognizable as a mutant. Jennings states that because Kitty is also visually white she could not experience the same kind of prejudice as Stevie Hunter. However, Jennings limits himself to discussing the story as solely an allegory for racism and does not acknowledge another part of Kitty’s minority status. Like Magneto, she is Jewish and a mutant. She regularly wears a Star of David and her grandfather was a Holocaust survivor. When the character was first introduced in Uncanny X-Men 129 (January, 1980), she was depicted as a resident of the Chicago suburb of Deerfield, IL. Chicago’s Marquette Park held neo-Nazi rallies in the 70s and was the headquarters of the National Socialist Party of America. Another Chicago suburb, Skokie, a city with 7,000 residents who were Holocaust survivors, was infamously the site of an attempted neo-Nazi march in 1977. It is safe to say that Kitty Pryde is well aware of that kind of prejudice through experiences with anti-Semitism.

The evening after the fight, the X-Men gather to watch an ABC news debate between Stryker and Professor Xavier, secretly the leader of the X-Men. The scene illustrates the role played by the media in debates with bigots. The TV station creates a false equivalency between the views of Stryker, who wants to eliminate mutants as a race, and Xavier, who argues for the humanity of mutants and that mutants should be judged as individuals. Watching the debate, Colossus complains, “They have switched to a commercial! They should’ve given the Professor a chance to respond.” Even one of ABC’s employees is aware of the weight of Stryker’s words saying, “He comes across as such a nice, personable guy… Too bad—’cause the man’s message is pretty damn scary.” We can see this attitude reflected in a modern setting when the CEO of CBS said the 2016 Trump Campaign “may not be good for America, but it’s damn good for CBS.”

At one point in the story, Stryker kidnaps Professor Xavier and uses a machine to brainwash him and weaponize his telepathic powers to commit genocide against mutant-kind. While mind control plots are fairly common in the superhero genre, in the context of this story, it is analogous to the discredited and harmful practice of “conversion therapy,” which holds that it is possible to convert queer people to heterosexuality. The sequence is given an orange/red coloration, giving it the appearance of Hell. Xavier is mentally assaulted with horrific religious imagery (this is the source of Robertson’s complaint about alleged blasphemy) in an attempt to turn him away from his mutant-ness. Anderson’s art is as important to the effectiveness of the story as Claremont’s writing. His characters and environments are frequently draped in shadow, giving the story a frightening, claustrophobic feel. God Loves, Man Kills is visually distinct from the standard monthly issue of the X-Men series, giving its message greater emphasis. Years later Anderson said he was “gratified and validated by Pat Robertson on his 700 Club televangelist TV show holding up that scene on camera and condemning it for being “blasphemous.”

At Reverend Stryker’s climactic religious rally, there is a sly reference to President Reagan’s friendship with fundamentalist televangelists through the presence of a White House aide who says, “The President is a fair minded man. He believes the Reverend’s views deserve a hearing.” Then, the X-Men, who have desperately allied with their enemy Magneto, rescue Xavier and confront the man of God in another of the book’s most memorable scenes. Stryker points an accusing finger at Nightcrawler snarling “You dare call that…thing human?” Kitty Pryde shouts back “More human than you! Nightcrawler’s generous, and kind, and decent! He had every reason to be bitter, every excuse to become as much a demon inside and out, but he decided he’d rather laugh instead! I hope I can be half the person he is and if I have to choose between caring for my friend and believing in your god, then I choose m-my friend!”

God Loves, Man Kills remains one of the iconic X-Men stories and is a high point within Chris Claremont’s lengthy run on the characters. Previous X-Men stories had addressed the issue of bigotry, but this one addressed the issue in a somewhat more realistic fashion and combined it with a sadly still relevant attack on the growing power of the Religious Right. The themes advanced in the story continue to be a large part of the X-Men’s appeal, including in the classic advertisements for “Fall of the Mutants.” Pat Robertson is dead, but the views he espoused live on. Thankfully, so do the X-Men and the fight for justice, equality, and socialism.

Featured image credit: Wikimedia Commons; modified by Tempest.

Categories

We want to hear what you think. Contact us at editors@tempestmag.org. And if you've enjoyed what you've read, please consider donating to support our work:

DonateHank Kennedy View All

Hank Kennedy is a Detroit area socialist, educator, and longtime comic book fan.