Let them eat steak

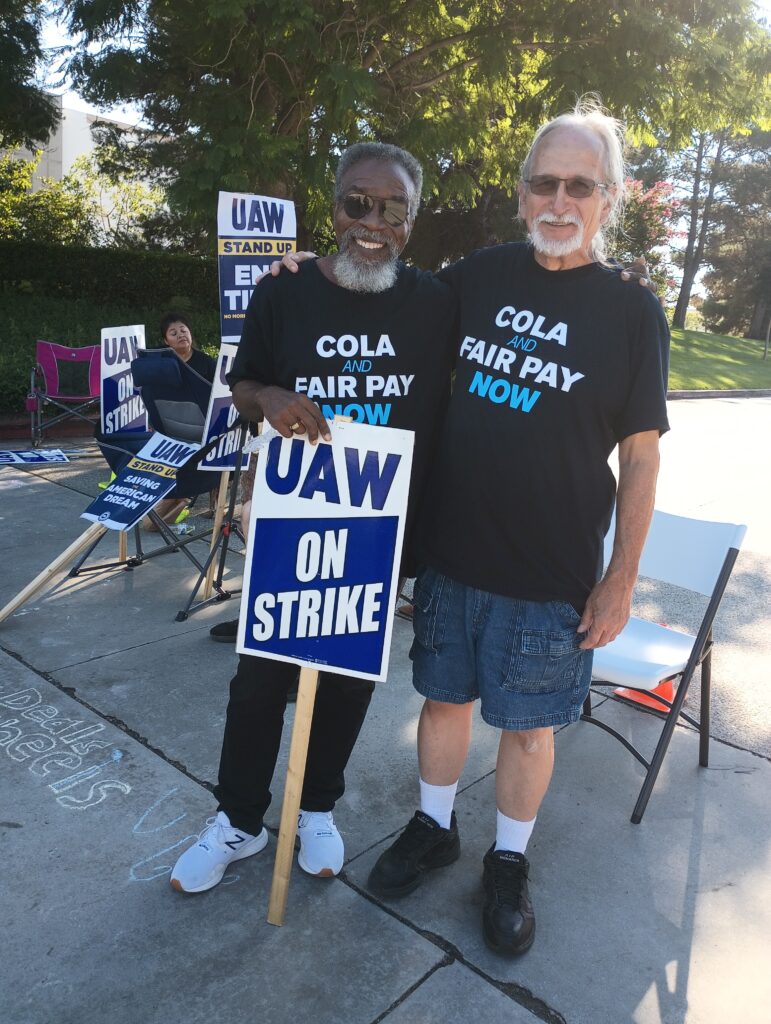

UAW Pickets at G.M. in Rancho Cucamonga

On the afternoon of September 26, I visited a UAW picket line at a G.M. parts distribution center in Rancho Cucamonga, CA. The workers there belong to Local 6645. Because the center only employs sixty workers, and they are deployed to the picket lines in rotating shifts, there were only about six people walking the line that afternoon. I spoke to five workers at length about the strike, the reasons behind it, and what they hoped to achieve.

On the question of tiers

Everyone agreed that the biggest issue is a tiered wage structure that starts and caps newer employees’ salaries unfairly low relative to longer-term employees.

A worker who asked to be called Sarah M. is a picker in the facility. Although she has worked there for six years, she earns just 17 dollars an hour and maxes out, given her occupying a lower tier, at $25. “We’re out here to get rid of tiers,” she said.

Michael Reed, a machine driver, told me, “You got some people doing the same thing as me, driving the machine around. They can pay people who’ve been around 37 [dollars an hour], and another person will get 24. You don’t want to be doing the same work as somebody over there and getting half your pay.”

Workers emphasized how the tier system is not only unjust, it also divides the workforce. Charles Dones, a worker with 46 years on the job, told me, “Traditionally, when you hired in and you did your 90-day probation, then you were equal to the guy who had five years. You were all one family. Now the disparity in pay creates an innate friction.”

The picketers were clear in blaming the company for the tension created by the tier system. Lou Varga, president of the Local, commented, “It’s kind of like a divide-and-conquer strategy. They use every tactic in the book to keep us divided. Tiers are unfair in principle. But they also keep people divided from one another.”

Francis (no surname provided) echoed this thought: “The thing about it is that you can’t have people doing the same job and getting different money, because then you get a little bit of animosity going on. That’s just unfair.”

Seeking redress of bailout givebacks

Another issue discussed at length is the demand of the union for a forty percent across-the-board pay increase in the context of workers’ sacrifices during the 2009 bailout. Reed explained, “During the economic crisis, they went through financial trouble. They took a lot of stuff away. And then they built on that by having more tiers.”

Sarah M. said, “We may never reach what we had before the bankruptcy. We gave back stuff to help them. Then they implemented tiers and tried to take away our insurance. That’s a hard no.”

Longtime worker Charles Dones explained, “We’re striking for things that we gave them to help them when the company was struggling. We just want them back.” He put it this way:

It’s like you’ve got a brother-in-law. Hey, he wants to start a business. He’s struggling, so you loan him some money. His business gets going and now he’s profitable, but he never pays you back. And every time you come over to his house, he pulls the shades and turns off the lights. That’s the way the company has treated us since 2009.

He added, “Cars have done great since then, but our pay hasn’t. I’m making $3.87 more now than I made in 2007. Adjusted for inflation, that’s a big pay cut.

Francis described the goal of the strike: “All we want to do is get the same wages. Everybody could survive then. The same wages and a raise commensurate with what the bosses get. These guys get, what, forty percent? We want the guy who’s making 18 bucks an hour to get forty percent.

On the “stand-up” strike strategy

The UAW is deploying an unconventional strike strategy dubbed the “stand-up strike.” In contrast to the sit-down strikes of the 1930s and the mass walkouts of other strikes, the union is calling out workforces gradually, increasing the number of struck facilities each week. We’ll know when the dust settles whether this innovation was a good idea. But the workers on the line in Rancho Cucamonga seem to favor it.

One reason they gave for supporting the strategy is its economic feasibility for the union and workers. Workers’ going out at one plant, say, a parts facility, affects plants that need those parts. The workers at that second plant are idled—they get laid off. But because they aren’t technically on strike, they can claim unemployment insurance rather than burdening the strike fund. “You’re still creating work stoppages,” said Dones.

In addition, workers from other not-yet-struck facilities come out to the strikers’ picket lines in support.

A second reason to think that the stand-up strike could work is how it puts gradual pressure on the companies while giving them an opportunity to bargain at every step.

Sarah M. noted, “The way that [union president Shawn Fain] has it situated, we can hold out for a lot longer. It’s also a change from what they expected, striking all three companies at once so that all of them are taking a hit.” She added that the strategy offers them the opportunity to do right by the workers as the strikes have “more and more of an impact on profit.”

Francis said that they weren’t hurting the companies badly yet because not all of the workers are out at once. But, he said, at some point, “You gotta punish—I guess you can call it punishing them—because they’re not making money.”

Overall, the workers of local 6645 feel strong and hopeful about the outcome of the strike. Sarah M. said that being on strike with the union meant that someone has your back and they are sticking up for your rights.

Dones said, “We’re going to be out here as long as it takes. Because it’s a just cause, and it’s not just for the UAW, but for all workers. Everybody’s tired of being exploited. Everyone.

Let them eat cake steak

While workers at the Big Three struggle to get by, their bosses are raking in huge profits. This gross inequity is at the heart of the strike.

Reed explained, “The pay is not good at all. Me, myself, I can’t afford the cost of living, especially in California”:

I have kids, so I would love to get them in school in the future. Get them through college. This is why I come to work, put a smile on their face, get them in school, get the things that they want. I have to start planning a future now. And I won’t be able to do that if I don’t have what the union’s asking for.

Francis commented about another worker,

He wanted to go out and get a loan. And this is after he’s been here a year. He can only get up to $200,000. You can’t buy a house for $200,000 in California. If you can’t make enough money to buy a house or even live in this state, then you have to do something different…. You see these guys here waiting, young kids, waiting to buy a house. They want to. They can’t.

Dones said that he also could not afford to buy his own house, purchased in 1999, if he had to today. Workers also commented on the irony that G.M. pushes them to buy company-made cars but doesn’t pay them enough to do so.

In contrast, they called out the company for pleading poverty. Varga stated,

They gave themselves a forty percent raise, and their salaries are in the millions. How do they justify that? Because when you’re the one who sets the pay scale, you pay yourself what you want. They say, “Well, I don’t have anything left over for you. I gave it all away.” Yeah, to yourself

On that point, Dones told a story:

I had a friend and she and I got into a dispute. She was telling me that the company’s got to make [a] profit, they have to pay this, they have to pay that, they have to buy this, they have to do this. And I said, “Whoa, whoa, whoa. Profit is what you have left over after all that stuff is done. Profit is after all the bills are paid.” And they have billions left. They raised their own pay forty percent over the last four years.

He carried on:

Watching those at the top of the corporate ladder raking in millions and then telling you, “Oh, well, we can’t afford to pay you more. But I can afford to own five yachts. Five. I can have three mansions. Not just one. I can take a joyride into space.” There are billionaires in space. And they’re telling us we can’t have a raise in the floor of our wages.

In a mic-drop moment, he concluded, “So, remember Marie Antoinette? What does she say about the peasants? ‘Let them eat cake.’

“So now we’re tired of cake; now we want some steak.”

Featured image credit: Dana Cloud; modified by Tempest.

Categories

We want to hear what you think. Contact us at editors@tempestmag.org. And if you've enjoyed what you've read, please consider donating to support our work:

DonateDana Cloud View All

Dana Cloud is a Tempest Collective member and scholar of Marxism, popular culture, and social movements currently teaching at California State University, Fullerton.