Starbucks: the long haul from recognition to a national contract

From a State Street Starbucks worker:

Our union sympathetic manager has quit because he “can no longer ethically work for this company” Our new store manager has been selected and is a universally disliked leader who is known for firing union organizers. We have also learned that our district manager expects our store specifically, though not others, to follow a scheduling system made by an AI. Because of this, in the school year when we typically have about 50+ workers, we are now being told we will not be permitted more than 25 workers, including supervisors and the store manager. Our outgoing store manager told me that this is not only to cut labor even more but that it is a tactic to wear workers down, presumably to the point they are just so exhausted they either A. Quit or B. Fail to perform to new standards so they will be fired. After that, corporate will likely return to full staff with new hires brought in to decertify the union.

This worker’s account shows how badly Starbucks workers need to claim their power. They have decided to unionize in at least 200 locations throughout the U.S. However, as might be expected, Starbucks has refused to negotiate a contract with any location. The company has been fined for unfair labor practices and has even agreed to reinstate some workers. But the NLRB process itself is fatally flawed. It is clear that we must find other ways to alter the balance of forces so that Starbucks understands that it is in their best interest to negotiate a fair contract with unionized locations.

The NLRB thicket

In the 1930s, the NLRB was set up to regulate union recognition battles then erupting across America. It was not designed to facilitate union organization but to channel it. Over the years, especially with the passage of the Taft-Hartley act in 1947, and through various court decisions since then, many of the tactics that unions used to organize and encourage firms to bargain were ruled to be illegal or unfair labor practices.

There is more bad news on the labor law front. Companies have developed the deadly art of delay. As Megan K Stack described the situation, Starbucks just did what companies do. In ways that are perfectly legal, they delay, delay, and delay until a union victory appears fruitless to those that organized the union in the first place. The process of delay effectively undermines the union’s power. Extreme turnover in industries like Starbucks and food service in general means that delay can mean the people who voted for a union are not there when the firm mounts a decertification challenge to the union.

Extreme delays also make it harder and harder to convince workers that it’s worth risking their jobs for a contract that can’t be realized in their time as workers there. As reported in the publication Dollars and Sense, the average length of time it takes to obtain a first contract after winning a union representation election has increased from 375 days in the years 2007 to 2007 to 575 days in the years 2020-2022. An increase of 35 percent. The article also points out that after 3 years, 32 percent of those unions formed more than 3 years ago still do not have a contract. At the same time the number of union representation elections is increasing: 1522 in 2022 with a 76 percent union win rate.

It is true that in some cases unions can file unfair labor practices cases demanding that the company negotiate or order the reinstatement of a person fired for union activity. Even should the union win, the remedy is generally to make whole; that is, to hire the person back with back wages. Most workers are in no position to wait the year or two (plus appeals) that such cases can take. In addition, the NLRB cannot impose monetary penalties.

Just in case delay and appeal did not stack the deck enough, firms (or unions) can also appeal. Even if the National Labor Relations Board makes a decision and administrative law judges concur with that decision or make their own, it can be appealed in the federal Courts. But as Take Back the Court reports, more than 80 percent of Supreme Court rulings favor the corporations so that actual implementation of a pro-worker ruling can be delayed for years, and when it gets to the Supreme Court, there is a 4 out of 5 chance that the ruling will be pro-management.

In any case Congress has been unwilling to pass legislation to improve the process to even come close to balancing the playing field, never mind providing meaningful protections for workers who seek to organize a union.

Given that history, think of what it would take to make American labor law correspond with the rest of existing law. For example, in the rest of society, punishment (jail time, fines, etc.) are imposed after a trial and a finding of guilt. In labor law, the opposite is true. Punishment (suspension or firing) is imposed by management immediately, and then at some future point a trial is held.

Clearly, the NLRB route doesn’t work.

But the limits to what by the NLRB process can impose are only part of the problem. As the New York Times pointed out so clearly, Starbucks, in its efforts to defeat unionization, simply did what companies do. So far, there have been no egregious physical assaults on workers, mass closings of Starbucks shops in a city, or widespread discharges. These are not the iron and coal police of Pennsylvania in the 1930s. Delay, delay, and appeal are the methods of choice to defeat the union, and these are all legal. Every once in a while, Starbucks gets out of line and is charged with an unfair labor practice, but these instances are neither widespread enough nor costly enough to force any changes in the company’s behavior.

There are other barriers to organization in firms like Starbucks that go beyond labor law. Starbucks has thousands of workplaces, and although the presentation of products and the culture of the location are determined at the top, the multiplicity of locations means that there is a lack of employee concentration. This employment structure effectively makes it more difficult to use the strike weapon.

An effective strike shuts a company down, inflicting enough pain to force management to the table for meaningful negotiations. It provides enough leverage to alter the balance of forces between management and labor. But a strike at Starbucks, which operates 9,000 stores in the U.S., would have to involve a much larger number of locations than the union has currently organized to really impact the company’s financial performance. To an extent, the effective use of social media and communication systems like Zoom can overcome only some of the challenges.

Is it possible to conceive of a solution within the current legal and organizational framework to achieve contracts? Is it possible to conceive that a firm could agree to implement a neutrality agreement that in effect allows the union to campaign for recognition without opposition from management? Such an agreement, negotiated at the top between union leadership and Starbucks, could, in theory, level the playing field.

But a neutrality agreement with teeth in it usually results from an effective nationwide corporate campaign of a scope and popularity of the United Farm Workers campaign against Gallo wines a generation ago. Looking at a company like Starbucks, a corporate campaign would also have to include a serious financial offensive as well as a political offensive beyond the scope of a consumer boycott.

A variant of neutrality would require the company to agree to neutrality during an election as well as an agreement to accept a contract, national or regional, covering all the employees who vote for a union. The agreement between the United Auto Workers and General Motor after the Flint sit-down strike ended in 1937, the General Electric agreements with United Electrical Workers, and the agreement between the United Steel Workers and U.S. Steel in 1937 were of this type.

While neutrality or outright union recognition pending a vote has been successful in many public sector campaigns, the private sector is another question. Absent political pressure available in the public sector, we have seen that these agreements do not necessarily result in union victories—as has been the case with the United Automobile Workers at Mercedes Benz in Alabama. Indeed, a meaningful neutrality agreement is possible only when it mirrors the situation on the ground, thus becoming an agreement that enables the already-existing organization and impulse of the workforce. It is a ratification of democracy, not a system to replace it.

Specifically, the union would have to be acting like a union,organizing departments or groups of workers to be demanding fair treatment, better schedules, or action on health and safety complaints. Public actions supported by a majority of workers are needed to get noticed and show that collective action is worthwhile. If these small actions are supported by a majority it is very hard for management to impose discipline illustrating strength in numbers.

A short look at U.S. labor history

In the 1920s, working people faced a grim reality. All of the hi-tech industries of the day–auto, electrical, steel, paper, and chemical–were almost completely nonunion. To say that these industries were nonunion understates the situation, as many of these firms had their own police and thugs, as well as the courts, to attack workers who wanted to organize. It was also obvious that the dominant labor organization of the day, the American Federation of Labor, and its craft-based orientation were simply incapable of organizing the new industries.

As the 1920s rolled on, more and more workers realized that they needed a new form of organization; they developed the industrial form of organization–essentially a wall-to-wall approach. Everyone in a location would be in the same union. This realization was stimulated by groups of class-conscious workers, many of whom were in socialist or communist organizations. The new form of organization resulted in the unionization of General Motors, General Electric, U.S. Steel, and others.

Today, major industries–from technology to food service–are unorganized. If the union movement is unable to organize those firms, it will become increasingly marginalized. The GEs and GMs of yesterday were the Apple, Amazon, Epics, and Starbucks of today. Meanwhile, as in the past, workers in those firms are crying out for organization and, in many cases, taking steps to do it themselves.

Moving forward: Doing the same thing more vigorously will do nothing

It is clear that if the company continues to do what it does naturally and organized labor does the same, then the results will be the same–derailing or stifling the movement.

The implications of this assessment are obvious. Progressive workers fought within the AFL to organize the unorganized along industrial lines.

This form of organization, necessary to win contracts with firms like Starbucks, will require innovation in the way we precede. The source of that innovation will be a focus and mobilization of progressives within the labor movement to force changes in the way we operate. The change envisioned is a change of attitude from defensiveness or passivity to one where the local labor movement is on the offensive. This means that our local labor and progressive organizations should not wait until workers come to this conclusion , but to be out there in the community and the workplace with the message that we are here for you. Starbucks workers–and all workers attempting to organize must know that even beyond the union, the labor community has their backs.

Those changes will make it possible for the labor movement to enable Starbucks workers to win. The Starbucks workers, just as workers in other generations and other circumstances, seem to be able to organize themselves and appeal for outside help to secure a contract. It is that next step–winning the contract–that will require political and organizational mobilization.

What existing structures are at our disposal that could be a basis for change?

If it is too costly for Starbucks to maintain their massive resistance to unionization in any particular market, the company will either abandon that market or agree to a contract. Obviously there is a limit to the abandonment strategy.

Denying the company their market is the best remaining option for the workers involved. The labor movement has a structure in place that can serve as a basis for a campaign of support for Starbucks workers. There are several hundred labor councils in the United States. Many of them are in markets essential to Starbucks growth. In addition, there are hundreds of progressive community centered groups, many focused on dealing with specific working class issues which could join any labor council initiative to support Starbucks workers.

If those labor councils, as a matter of policy, mobilized their memberships to boycott Starbucks locations–no matter which union was organizing them–until the company recognized the union and signed a contract, perhaps we might make some progress.

Clearly there are barriers to this strategy. Not all unions are in labor councils, especially some of those organizing Starbucks workers. The disorganization of organized labor puts the issue of what progressives in those labor councils and in those unions organizing Starbucks need to do to place the interests of the Starbucks workers ahead of the parochial interests of their local union or labor council.

This strategy depends on the collective of unions in any area accepting the notion that union consciousness means challenging these barriers. This is no easy task, but it has the advantage of being clear. A program focusing its support for Starbucks workers will enable workers to take action. It also means that Starbucks workers, who wish to engage in organizing their workplace, will know that someone has their back.

The Starbucks workers will determine the best union or organization to represent their interests. That is their right. Maybe workers will develop new forms of organization as workers did in the 1930s; maybe not. But we in the labor movement have a responsibility to do all we can to find ways to move past the present impasse. We need a focused effort, city by city, area by area, to lend support to those workers who are now in motion.

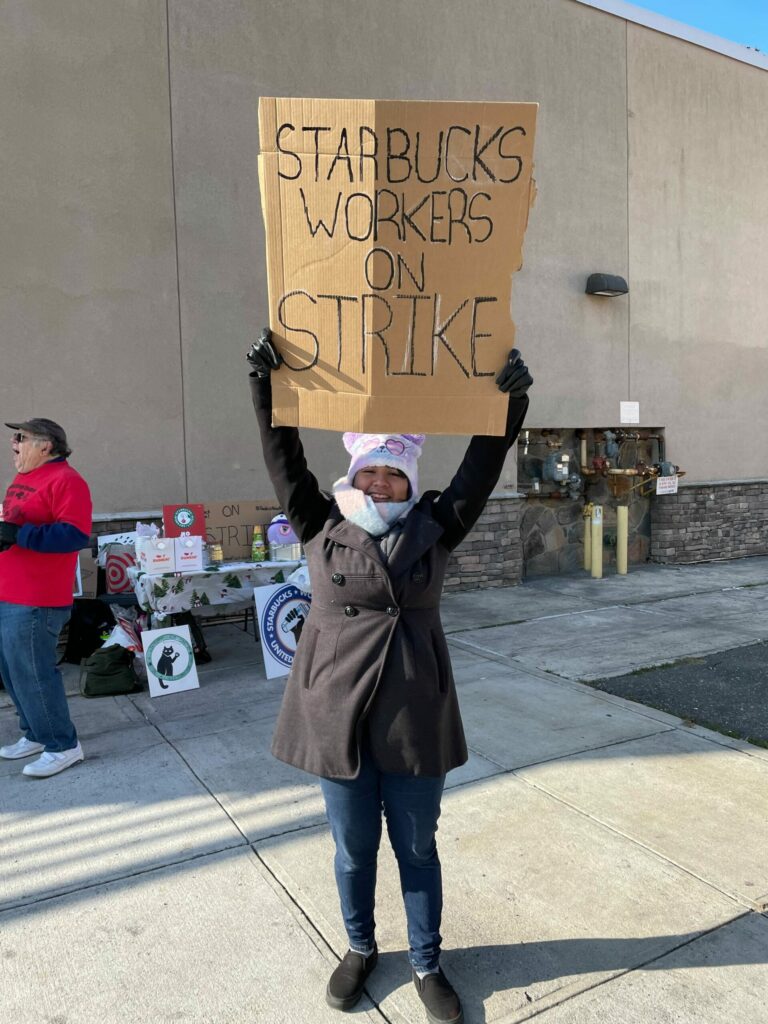

Featured image credit: Herman Cheah, modified by Tempest.

The author would like to thank Mike Locker for his suggestions and assistance in developing this article.

Categories

We want to hear what you think. Contact us at editors@tempestmag.org. And if you've enjoyed what you've read, please consider donating to support our work:

DonateFrank Emspak View All

Frank Emspak is professor emeritus of the School for Workers, University of Wisconsin. His union experience includes serving on the executive boards and negotiating committee of UE Local 271 and IUE local 201(GE Lynn MA); and as president of United Faculty and Academic Staff (UW Madison AFT Local 223) and a vice president of the AFT-Wisconsin. Currently he is the producer of Madison Labor radio, a 30 minute news program broadcast every Friday at drive time on WORT 89. 9 FM; Madison WI.