Celebrating pride month

while our rights are under attack

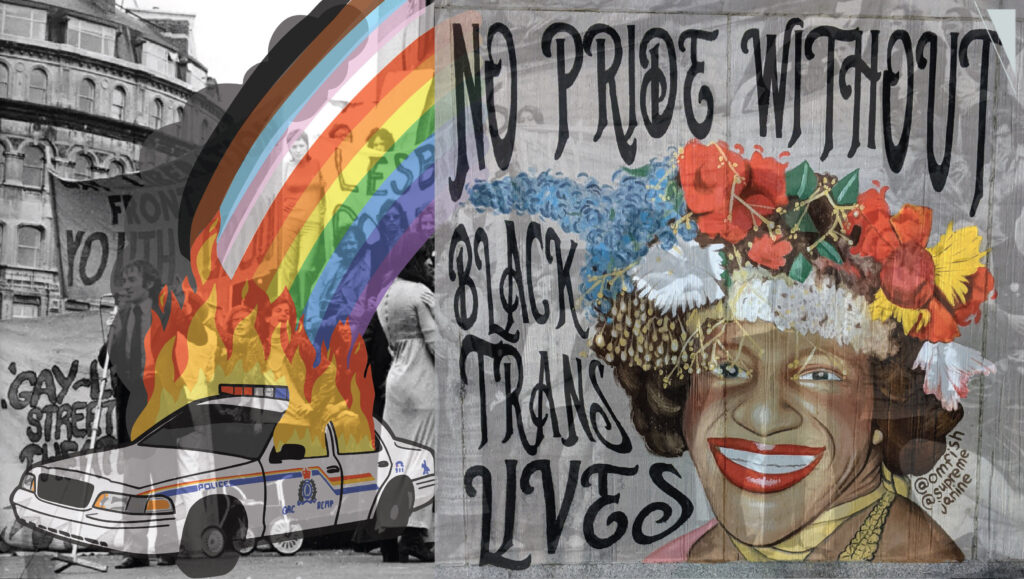

June is pride month. It marks the anniversary of the Stonewall Rebellion, a pitched street battle between working-class queer people and the police following a routine raid on the Stonewall Inn on this date in 1969. For six days following the raid, queer people occupied several blocks of New York City’s Greenwich Village in a seemingly spontaneous eruption of anger and resistance. Like other bars frequented by queer people at the time, the Stonewall Inn was operated by the Mafia, and for a cut of the profits, the police agreed to look the other way. Despite this arrangement, periodic raids took place, and patrons were often roughed up or arrested for violating the city’s gender-appropriate clothing statute. In the recently released book Miss Major Speaks, Stonewall veteran and queer movement mother, Miss Major describes the complicated and contested history of the Stonewall events:

All I know is that night they [the police] came in, and nobody budged. I guess we were just sick of their shit. And suddenly we were fighting, and we were kicking their ass…. “The Night of Stonewall” is how people talk about it, but it was more like a week. People want to know all the details, but mostly I remember being scared as hell. We were fighting for our lives. They are still killing us. (37)

Stonewall and its legacy remain important to our understanding of queer resistance for many reasons. For one, the most precarious members of the LGBTQIA community, Black and Brown trans feminine people, as well as those making a living outside the formal economy, were at the forefront of the fightback—a dynamic that fueled the radicalism of the moment. Fifty-one years later, amid the wave of protest following the police murder of George Floyd, another monumental action that centered the most precarious of the LGBTQIA community took place. Brooklyn Liberation: An Action for Black Trans Lives brought 15,000 people into the streets of New York in 2020 and is already recognized as a watershed moment in the history of trans liberation. It is an action that lifted the social and political struggles of trans people out of the margins and into the political moment’s mainstream.

Organized by the Okra Project, the Marsha P. Johnson Institute, GLITS, For the Gworls, and Black Trans Femmes in the Arts, the action marked the 18th day of protest in what has become known as the George Floyd Uprising and took place just days following the Trump administration’s reversal of the federal Health and Human Services LBGTQ anti-discrimination policy. Ianne Fields Stewart, a Black transfeminine actor, storyteller, activist, and founder of the Okra Project addressed the crowd that day insisting,

Today is the last day that a Black trans woman fears for her life…the last day a Black trans man fears occupying physical space…the last day that Black nonbinary people feel forced to fake themselves into a binary that doesn’t exist.

The protest embodied the true legacy of Stonewall and was characterized by both an air of defiance and celebration.

But three years have passed, and since the Brooklyn Liberation March, a reactionary backlash has swept the country. Framing this attack as a culture war, right-wing pundits and the MAGA wing of the Republican party have amplified attacks on immigrants, Black and ethnic studies, and LGBTQIA people–particularly trans people in efforts to roll back ideological gains made by the Black Lives Matter movement and to buttress the campaigns of right-wing populist candidates. Presently, the ACLU is tracking over 490 anti-LGBTQ bills that have been introduced in statehouses across the country; 57 of them have already become law. At the same time, queer and trans people have become the target of increased conservative media vitriol and continue to experience acts of street violence.

At Tempest, we look to the Stonewall Rebellion and the Brooklyn Liberation March not to romanticize or mythologize these actions, but to learn from them. Notably, both actions draw our attention to the overlapping oppressions of race, gender, and sexuality, and remind us of the centrality of police in disciplining the boundaries of social locations under capitalism. Because queer and trans bodies are devalued by capital, they are often pushed into low-paying care work or work outside the formal economy (often in the form of sex work). This economic precarity leads to disproportionate contact with the carceral system. A 2018 report by The National Center for Trans Equality details:

A history of bias, abuse, and profiling towards LGBTQ people by law enforcement, along with high rates of poverty, homelessness, and discrimination in schools and the workplace has contributed to disproportionate contacts with the justice system, leading to higher levels of incarceration.

In fact, transgender and gender-nonconforming people experience incarceration at twice the rate of the general population, and 47 percent of Black transgender people report having been incarcerated at some point in their lives. These material realities inform a queer politics that is not concerned with corporate inclusion or multicultural representation, but one that addresses the harms of economic inequality and carceral logic, as well as the specific forms of oppression that queer and trans people experience. In this sense, queer and trans liberation are intimately tied to the fight for abolition and the struggle against class exploitation.

The first Pride may have been a riot, but for queer socialists, Pride continues to be a demand for investment in our communities. For Tempest, Pride is not a billboard or a company logo. Neither is it an empty political statement. Instead, it is a commitment to understanding and fighting against the specific forms of gender discipline and oppression that queer people experience. Our Pride is one that not only celebrates our identities and defends the hard-won rights of our movement, but also decriminalizes sex work, insists on needle exchange programs, demands free gender-affirming care for all, and presses for investments in housing and education. At this moment, we must rebuild movements for queer liberation, taking inspiration from those who have gone before.

Featured Image Credit: Eden, Janine and Jim; Zola; Collage by Nevena Pilipović-Wengler.

We want to hear what you think. Contact us at editors@tempestmag.org. And if you've enjoyed what you've read, please consider donating to support our work:

DonateEric Maroney View All

Eric W. Maroney teaches English at Gateway Community College in New Haven, Connecticut. He is a member of the Tempest Collective.