The dialectics of defeat—lessons from the United Kingdom

A Review of This is Only the Beginning

This is Only the Beginning

The Making of a New Left From Anti-Austerity to the Fall of Corbyn

by Michael Chessum

Bloomsbury, 2022

Michael Chessum’s recent book This is Only the Beginning is invaluable both in capturing the development of the British Left after the financial crisis of 2007-2008 and in grappling with its lessons. The book is broken into two parts, the first dealing with the period from 2010–2015, with a focus on the student and anti-austerity movements. The second, covering 2015–2020, addresses the rise of Jeremy Corbyn as the leader of the Labour Party, and the experience of Momentum, an organization founded in 2015 to support Corbyn and the movement which coalesced around him.

Chessum frames his analysis in ways that should ring bells for many readers well beyond the United Kingdom. “The different versions of Corbynism’s origins and demise are far more than just disagreements about the past. The different narratives about why the project happened and why it failed…are really questions about what the Left should do now.” Introducing the book, Chessum writes,

[T]he mass revolt that took place in the early part of the decade can and must be understood as containing the seeds of a new left—less hierarchical and sectarian, more democratic, radical in its tactics and determined to break free of the confines of conventional electoral politics. Within the new Labour left, it was overshadowed and consciously defeated by better-organized institutional tendencies within the party, but that is not the end of its story. (7)

Rebellions at the end of history

This is Only the Beginning (TOB) opens with an account of the “rebellion at the end of history,” the 2010 Battle of Parliament Square, and the mass student revolt against the political betrayals that ultimately led to a tripling of student fees and the “full marketization” of the U.K. higher education system. In that year, the Tories narrowly won a plurality in the general elections after 13 years of neo-liberal Labour governments. The Tories formed a coalition government with the Liberal Democrats who had run to the left during their campaign and then veered sharply to the right while in government. Chessum describes in detail the evolution of a revolt that culminated in the march of tens of thousands of students across the country, the battles with the police, and the occupation and trashing of the Conservative Party headquarters. The story is especially compelling because he situates this account in a narrative of a broader “rebellion at the end of history,” a rejection of the inevitability and permanence of late neoliberal consensus and the prison of capitalist realism.

Chessum’s historical account describes the relationship between successive waves of the student and anti-austerity movements, while also pointing at tensions among different sectors. With the defeat of the student movement, the banner was picked up by the broader anti-austerity movement. Despite its defeat at the end of 2010, student organizing continued, and spread to the union of lecturers, who struck across campuses in 2011. The book includes vivid descriptions of the huge anti-austerity demonstrations in 2011, and highlights the confluence of labor, student, and anti-austerity struggles across Britain through the summer of 2011. This coordinated activity opened up the possibility for an united, cross-sector mass strike action similar to the widespread labor unrest in Britain in 2022 and 2023.

Chessum helpfully delves into the strategic and tactical impact of the student and anti-austerity rebellion on the trade union movement, describing arguments about the limits of one-day strikes and the need for more militant actions led by activists to replace largely symbolic set piece marches in which union officials regard the rank and file primarily as foot soldiers. He also describes the challenges of a default anarchist and horizontalist politics that was hegemonic outside of the trade unions. Placed in the context of the international events—including in Egypt, Greece, Spain, and the United States—the book describes the hopes arising from the Red November in 2011, which culminated with “the biggest single day of strike action since the general strike of 1926” involving twenty-nine unions, two million workers, and mass student participation (“[a]lmost 70 percent of schools were shut entirely and many more severely impacted)” (95).

TOB painfully details both the specific defeat at the precipice of an all-out battle over pension reform in the winter of 2011–2012 and the subsequent contagion of defeat across the student, anti-austerity, and labor movements. In later 2011, the unity across sectors was undermined by the government, with different trade unions cutting concessionary deals with the government. The movement collapsed. Chessum’s description of the “deep-seated fatalism” and “defeatist realism” that followed “at the highest levels of the trade union movement” is disturbingly familiar (96-98).

Corbynism and Momentum

Chessum explores the relationship of the various movements toward the government, electoral politics, and the Labour Party throughout the first half of the book. The Liberal Democrats, junior partners in the Tory-led government of David Cameron, had promised to introduce free higher education before doing a complete reversal and supporting the tripling of fees and wider privatization in 2011. The milquetoast pro-austerity “realism” of Labour Party leader Ed Miliband is a backdrop to the 2011– 2012 struggles and defeats. As is the presence and support of the marginalized stalwarts of the anti-austerity movement within the Labour Party left, including Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell, which presaged the events leading to the election of the former as Labour Party leader in September 2015.

Every cycle of social upheaval in modern time in Britain has been subject to the same tidal system which has drawn generation after generation into the Labour Party and then spat it back out again. Corbynism undoubtedly represents the extreme version of this phenomenon, however. As the social movements began to ebb in the run up to the 2015 election, there was already a natural but very modest influx of new recruits on the Labour left, but…Jeremy Corbyn’s victory…had the effect of turning the social movements on their heads. Suddenly politics became about trying to win elections and take control of a political party. The vast majority of the new recruits had no collective understanding of the task at hand…they had no collective organization either, nor even a space in which they could discuss and develop a strategy beyond cheerleading (116).

In the second half of the book, Chessum tells the story of Momentum, the organizational vehicle for the Corbyn movement, and the enmity with which the Labour Party establishment—in fact the whole British establishment—treated Corbyn’s election. TOB describes the Corbyn movement as a coalition of a fading older generation of the Labour left, a younger generation of recent social movements, a soft-liberal left, and the trade union movement, which provided the organization and financial weight to sustain the project for a period.

Between May 2015 and June 2016, Labour Party membership surged from 190,000 to 515,000. In parallel, Momentum became the organizational vehicle for tens of thousands of those activists across Britain. However, even at its inception, Momentum members held different visions of its project. One was as the organizational voice for a radicalized, geographically dispersed, broad left in support of Corbynism. The second as the space of a renewed Labour left that aimed to win the institutional fight to control the Labour Party and win elections. The later chapters of TOB are largely focused on these competing visions and “a struggle for power between the left’s new activists and its old guard.” (142) Ultimately, the older Labour left and the trade unions won the battles to control Momentum, which set up the conditions that helped Corbynism “gain[] control of the Labour Party [and lose] its soul in the process” (166). 1

Just as in the student movement of 2010, the separation of a generation of left-wing youth from the history and tradition of the organized left had the effect of creating a free-flowing, unconstrained atmosphere. But it would also make the Corbyn project —with its promise of a new kind of politics and its attempt to create an all-embracing mass movement—vulnerable to being defeated and co-opted by the much better organized, more institutional left (145).

A generation without history

The second chapter, “A Generation without History,” describes the political polarization and radicalization of the post-2007 period. It describes “a generation whose political centre of gravity was decisively to the left of those which preceded it” (40, 41). And yet, “The real defining factor in the political development of the people who took part in the moment…was not their connection to recent social movements and industrial struggles but their distance from them; and if this generation of precariously employed debt-laden young people complained of having no future, they also had no past” (47-48).

Chessum’s approach is nuanced, however. He fully recognizes lines of continuity, and understands the role of the earlier generation of the organized far Left.

It offends the sensibilities of most commentators to talk about the British far left—the array of intellectual traditions, socialist grouplets, and acronyms that have historically given shape to much bigger campaigns and strikes—in a way that does not immediately bookend any analysis with a flippant remark about the People’s Front of Judea or some metaphor about dinosaurs. And yet the truth is that without understanding the organized left, and the relationship of the wider movement to it, you simply cannot speak with any clarity about the social movements that laid the ground for Corbynism. In the same way, so many mainstream journalists who had spent years laughing at the very idea of 21st century Maoism or Trotskyism would show up in Athens in the summer of 2015 and simply be unable to report on what was happening inside of Syriza…In truth the story of Corbynism, and indeed the rise of Bernie Sanders, is also a story of major changes within the left, in how it operates, and what its goals are. By the end of the 2010s, the organized far left in Britain were sucked into a very different kind of left politics within the Labour Party. (45-46)

This empathy and acknowledgement of the role of the far Left and the placing of the dynamics firmly within a context of the international Left are consistent throughout Chessum’s analysis. And yet, the point about generational discontinuity, the weaknesses of the far Left, and the impact on the subsequent development of the Left through the Corbyn period is inescapable.

At the level of both reporting and analysis, Chessum is able to offer insight as a first-hand participant and lead organizer in the movements of the 2010–2015 period. Details of the meetings, the color of the events, and the participants come across vividly. Chessum himself was a “full time student activist” (126) and student leader. He then covered the momentous events in Greece in 2015, before returning and becoming an activist and then a staffer within Momentum (a perspective that deeply informs the book). The author interviewed numerous figures across the British Left, and the list is impressive in its breadth and spread across all of the movements and a broad spectrum of Left politics. One of the notable feats of the TOB is Chessum’s empathy with the many voices he presents, their histories and contributions, regardless of political and strategic differences. This basic solidaristic approach to comrades in the movement is a real credit to the author and too often absent. Importantly, it is not at all an impediment to criticism.

The machine strikes back

TOB dives into the history of the Labour left going back to the 1970s, its institutional defeat by the late1980s, and its survival, largely at the margins, in the form of the Labour Representation Committee, the Greater London Council, and the Campaign for Labour Party Democracy. Chessum references a famous 1980 debate, “The Crisis and Future of the Left,” that included, among others, left Labour leader Tony Benn, Tariq Ali, Paul Foot, and Hillary Wainwright, who is quoted offering insights relevant to the Momentum experience.

Is the extra-parliamentary activity, the mass movements to which the Labour left give support, merely like “extra-curricular” activity, just a worthy backup to the real thing…the work aimed at bringing to power a radical Labour government? Or are extra-parliamentary movements like the women’s movement, some shop stewards’ combine committees, tenants’ groups, and others themselves the basis for a new form of political power? Are they the real thing for which parliamentary activity is just one source of support? (147).

Chapter 5, “The Movement versus the Machine,” describes in detail the organizational battle in Momentum between those two competing understandings of the role of the social movements of 2010–2015 without which Corbynism would have been inconceivable. Chessumm tells “the story of how the energy and bottom-up politics was ground down and absorbed into what would become an orthodox and conventional electoralist project” (151).

The penultimate chapter, “The Machine Strikes Back,” is a depressing but persuasive account of the impact of this dynamic. The victory of the top-down perspective of an electoralist machine led by the (old) Labour left profoundly disorganized and disoriented the movement forces that had been essential to Corbynism. The chapter offers a variety of examples, including the fights around deselection and the impact in the youth and student movements. But most important is Chessum’s account of Brexit.

[T]he fact that Brexit and Corbynism occupied the same moment in time was not a coincidence. They were products of the same conditions and, in a sense, part of the same process…All over Europe and in the United States, new left-wing projects emerged wielding a resurgent class politics…In order to sustain a winning electoral coalition behind a continued policy of economic orthodoxy, a section of the ruling-class elite consciously turned towards a policy of right-wing nationalism, protectionism, anti-migrant scapegoating and racism. (177)

The Labour Party policy of “constructive ambiguity” on Brexit, while offering short term benefits in the 2017 general election, was ultimately a disaster. Chessum argues compellingly that it was not the historical Euroscepticism of Corbyn, or his main advisers, that was the central problem. Rather the “lack of proper internal democracy and an orthodox party management strategy in which the trade union bureaucracies were encouraged to outmaneouver and overpower the wishes of members” destroyed any prospect of building an affirmative movement in response to a reactionary Brexit movement. While Chessum’s own left position is clear, regardless of one’s own position, the strategic argument is persuasive. The Left needed clarity and a coherent movement but this was never mobilized—and in fact actively blocked—by institutional forces on the Left, such as the labor officialdom.

Dialectics of defeat

“The death of Corbynism represented a moment of strategic crisis” (201), and for that (especially the English and Welsh) Left, the book assesses the roots of that crisis. In so doing, as a U.S. based reader, there is a powerful sense of deja vu, historic consonance, and an appreciation for this reckoning which much of our Left has blithely ignored.

In a late 2016 interview, following the release of his book Corbyn: The Strange Rebirth of Radical Politics, Richard Seymour presciently noted,

I think we’re seeing the possibility of regenerating a left that has previously been ground down to the scale of atoms, one that if it adapts creatively to the coming defeats can prepare the ground for success. But that means recognizing that the history of the left is a history of defeats; it is a history of the vanquished. We gain our victories out of a dialectic of defeats—from the crushing of the Paris Commune to the birth of mass socialist parties; from the horror of 1914 to the electrifying revolution of 1917. If we extend our thinking temporally, projecting the lessons of defeat into future gains, we can exploit this opportunity; if we expect instant gratification, we will just collapse in trauma and resignation.

Seymour’s insight is a crucial response to those who look at these histories and see nothing but inevitable defeats, and, as a result, argue for a return to the safety of the sect. More than four years later, and after the definitive defeat of the Corbyn moment, TOB implicitly reflects this wisdom.

While providing an ultimately depressing account of the internal battles within Momentum and the Labour Party, Chessum also notes the “paradox of the Corbyn moment” that the rebirth of a Labour left “did not translate into a flourishing of social or industrial struggle” (156). This parallels the Greek experience, in which the Syriza electoral upsurge, and its ultimate betrayal, only followed years of social struggle and mass strikes that had exhausted their participants. And it raises questions about the type of organizations we need, and their relationship to social movement and trade union struggle.

Quoting Hal Draper in the Two Souls of Socialism, Chessum points towards the confluence of “from-above” politics and strategy shared by the “professional” Corbyn leadership, the tradition of Fabianism that retained influence in that leadership, and the traditional Communist Party politics that informs many of the trade union officials who played a destructive role at a number of key moments in this story. In response, Chessum is insistent on the “creative mess of a genuine activist democracy” (206) without illusions in per se horizontalism and an inchoate default anarchist politics. He observes,

There is no contradiction between building activist networks with the freedom to act and having an organisational centre for the movement which can seek to coordinate….The task for the left in the next cycle of protest movements, then, is to rediscover autonomous action and the capacity to disrupt while building the infrastructure that might make this sustainable. The organsational centers of the movement will have to be non-sectarian, open and rigorously internally democratic, in contrast to what has come before. (207)

In this process, Chessum calls for the collective creation of a new generation of activists, not footsoldiers, and a “campaign against amnesia, not just…an attempt to teach and share history…and rebuild[] a space for ideological traditions and collective memory in a practical sense” (211).

Implications for the U.S. Left

“American” exceptionalism takes many forms. Even on the Left, where explicit national chauvinism should be anathema, parochialism too often infects our understanding of politics. The assumed imperatives of day-to-day tactical and strategic arguments can narrow our vision, excluding broader international and historical dynamics that are essential in orienting our movements and our organizing.

The last fifteen years have been marked by some of the biggest protest movements in a generation.2 Most importantly, and most recently, was the historic multiracial uprising in defense of Black lives in 2020. This represents a qualitative turn away from a period of relative neoliberal stability going back to the late 1970s.

Yet the U.S. Left has largely failed to critically assess the experience of left electoral efforts, most centrally that of the two Bernie Sanders campaigns. In Britain, Corbyn was defeated by the party establishment (the bulk of the parliamentary party and the full-time officials), which maneuvered to defeat him from the beginning. They always had the advantage but Corbyn made it easier by being unwilling to build a movement outside parliament that would fight for his program. The new leader of the Labour Party, Keir Starmer, has done everything in his power to kill what is left of the Corbyn movement, including depriving Corbyn of the Labour whip and refusing to let him stand as a Labour candidate in the next election. All of this history has valuable lessons for the U.S. Left, and our current collective state of disorientation and, with some local exceptions, demoralization remains unexamined, much to our discredit. In This Is Only the Beginning, Michael Chessum provides both an important template for how to begin such an assessment and offers critical insights that are equally applicable for socialists in the United States.

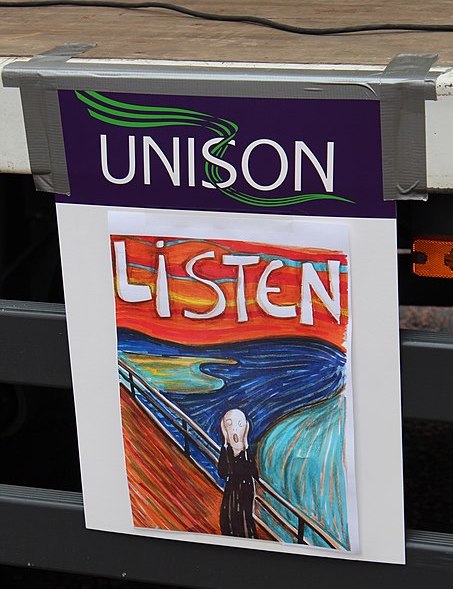

Featured Image credit: Jason; modified by Tempest.

We want to hear what you think. Contact us at editors@tempestmag.org.

Aaron Amaral View All

Aaron Amaral is a member of the Tempest Collective and serves on the editorial board of New Politics.