Venezuela: left perspectives from below

Eva María: Welcome everyone! Thank you for coming to this very important conversation. A special thank you to Simón Rodríguez, who’s going to be answering most of the hard questions.

I am a member of Venezuelan Workers Solidarity (VWS) and what we’re doing from the diaspora, as Venezuelans, is to build relationships with people and groups inside of Venezuela who are doing work that we think is essential to presenting an alternative to the current crisis. As VWS, we don’t think that what we’re seeing in Venezuela right now represents socialism or a revolutionary government.

The first question is one on most people’s minds today, as it relates to what solidarity with Venezuela, from the outside, should look like.

In the past couple of weeks, we saw what some socialists think is the best way to show support, when members of the Democratic Socialists of America went on a tour sponsored by the Venezuelan government. They attended government events, went on guided tours, and met a lot of government officials, including president Nicolás Maduro. This was heavily publicized by the official government press and TV channels as a show of support for the Government from the international Left. The delegation took to social media to express amazement at what they consider is Venezuelan socialism.

And so my first question to you is, does solidarity with the Venezuelan people and opposition to U.S. sanctions imply support for Maduro and the government?

Simón Rodríguez: Thank you, Eva. Well, this is a crucial question of what internationalism means, that obviously not only the U.S. Left but also European, Latin American, African, Asian leftists have to deal with. What does solidarity mean in a situation like Venezuela’s, that is on the one hand facing sanctions and political pressure from the U.S. government, but on the other, has a government that heavily persecutes working class activism and engages in constant attacks on union liberties. What should it mean to exercise solidarity with the Venezuelan people?

For one, we tried to warn this delegation of DSA before their travel to Venezuela about what they would encounter in this international meeting, what they should expect, and of what we thought they could have done differently to follow a spirit of international solidarity.

We warned that this was basically about self-promotion by the government: an official, government-sponsored event with people invited from the Chavista government and from foreign parties linked to the Venezuelan PSUV. There shouldn’t have been any expectations of debate or plurality, as it was an event to boast about international solidarity with the Venezuelan government.

We warned about the situation in Venezuela, which obviously you cannot perceive if you are in five-star hotels and meeting the constant government propaganda. We live in a reality of human rights violations, attacks on workers’ rights, miserable semi-slavery $2 monthly wages, union leaders that are jailed, massive and rapid environmental destruction in the Orinoco Mining Arc for gold extraction, destruction of the rainforest and the polluting of rivers… an political attacks on the rights of women. Abortion remains totally illegal in Venezuela. It’s only allowed, not if the woman chooses, but if a medical doctor decides that her life is a danger. This is 19th-century legislation.

One also has to point out the pervasive police brutality and killings of youth in the barrios. Venezuela has one of the highest rates of police killings in the world, carried out in large part by paramilitary death squads.

If you see the mainstream media you might get the impression that everything is state-owned in Venezuela. Well, actually it’s not. There is a wave of privatizations that is under way by the Maduro government.

We said all of these things in an open letter, which we sent several weeks before the trip; unfortunately, we did not get an answer. But we also suggested that on their trip, they should meet different sectors of the Left, beyond government supporters or PSUV members, such as the critical Chavistas of the APR/Asamblea Popular Revolucionaria. This is a sector of Chavismo that is critical of Maduro and upholds what they call ‘the legacy of Chávez’. This includes, among other parties, the Communist Party of Venezuela and Homeland For All [Patria Para Todos]. These are parties that were always part of the government coalition of Chavismo, but have recently started to present independent candidates in elections and have semi-critical positions regarding the government. And in spite of being a loyal opposition, or critical supporters, they have faced persecution and repression, so it would have been interesting for DSA delegates to meet them and to talk with them.

The delegation could also have met with left opposition Marxists, or activists in the labor, anti-extractivist or feminist movements, who every day fight for things very similar to what the Lefts in other countries struggle for.

The world cannot be divided into people cheering for Maduro or people cheering for Trump, there are other sides. Unfortunately, this delegation chose not to recognize this.

For us, solidarity means not only rejecting imperialist aggression and the U.S. sanctions specifically, but also standing with the rights of the working class, indigenous peoples, women, and the LGBTQ community.

These things for us are the embodiment of true internationalism, which is to side with your equals, with the people that belong to your same class, even if the frontiers that have been drawn by the bourgeoisie separate them.

EM: Thank you for that very thorough response, I think it actually covers a lot of what I was going to ask next. From what you’re saying about the pro-government optics, if you’re in the U.S. you see Trump and Guaidó, and their ‘show’. And then you also have these ideas of the Venezuelan government being revolutionary, pro-indigenous, anti-racist, feminist, ecosocialist, etc… Where do you think this impression comes from? Is that the impression that the majority of Venezuelans have of their government?

SR: Well, it can be expected that if the government says it is revolutionary and anti-imperialist, and if the right-wing says the same thing (i.e. “in Venezuela things are bad because of socialism and because there was a revolution, and this is what happens when you have a revolution”), then it’s inevitable for this common sense to be installed both inside and outside of Venezuela.

However, in Venezuela, we have the advantage that you cannot lie to people about their own experience and people know that high government officials are millionaires. They see the grotesque privilege in which the ruling class lives. They are not Che Guevaras, they are not sacrificing anything for an ideal. They are cynical members of a rising sector of the bourgeoisie. Many of them have themselves become capitalists. So, in that sense, it’s clear that we are dealing with a government that is not representing the working class or the working people. It’s obvious that they don’t live on a $2 a month wage. You don’t have to go into that explanation [with people living here in Venezuela], this discussion is unnecessary

You do have to do it when you are talking with people who don’t know Venezuelan reality, who live abroad. We then have an uphill battle to explain that, for us, socialism was never really attempted in Venezuela because the working class is not exercising power, relations of production did not fundamentally change. If we are not really dismantling the bourgeois state and replacing it with a direct democracy of the working people, the youth, indigenous people, the peasants, if we are not doing any of that, then we are not advancing to our own liberation.

On the economic level, of course, the main industry in Venezuela, which is oil, was never nationalized. The only moment when it was under workers’ control was in 2002 when workers took control of the industry to keep it in production and to defeat a coup d’etat and a lockout that was promoted by the capitalists to take down the government—but that was almost 20 years ago.

And there has been a change in the situation as right now it’s the Venezuelan government who appears in Bloomberg News trying to present itself as the best guarantor of the recovery of the normal cycle of production of capital. It’s a double discourse. Maduro says one thing to an audience from the Left of other countries, and another to Wall Street.

So then for us, it’s very important to have a clear understanding of what the regime is in practical terms, not only because we make some comparison between reality in Venezuela and some abstract principles or theories that we value as correct.

It’s not about comparing a perfect utopia with a semi-problematic experiment that is going on and that has its problems or that it’s facing the pressure from imperialism, which is the way that Chavistas will portray what the government is doing.

We have to look at the facts and to see what are the class relations in Venezuela, what is the concrete situation of the working class, and how this came to be even before the sanctions. Basically, to be honest, and to be loyal to the Venezuelan people, you need to try to learn from this experience and from history and not simply repeat slogans that really distort reality.

EM: As someone who radicalized—who became a socialist, a revolutionary, someone on the Left, trying to build a different world—part of what inspired me was Chavismo. I was specifically inspired by its rhetoric against the Venezuelan two-party system, which I absolutely disliked and distrusted, and the momentum around writing a new constitution that promised indigenous autonomy, the right to housing, and the responsibility of the State in meeting basic social needs.

What happened with that? Was that real, was that fake? What do you have to say about those early stages of Chavismo and what happened?

SR: My own experience has a similar trajectory and I mention it because I think that many people in Venezuela, especially on the Left, have gone through a similar process.

And it has to do with the Venezuela history that you mentioned, that there was a lot of discontent with the massive social inequalities of the 40 years of bourgeois democracy after the fall of the military dictatorship of Pérez Jiménez. And really, the breaking point was the massacre of 1989 [to repress an anti-austerity popular uprising, the Caracazo].

I was a very young kid, only seven years old, but I remember hearing bullets fired by the military against working people in the barrios. Over time, I started to interpret what this meant in the context of Venezuelan politics.

Really it showed that the governments of the social-democratic Acción Democrática and the social-Christian COPEI did not have any other way to respond to popular demand at that very dramatic moment than to send the military out to repress. That created a break in the military, although not an immediate one.

1992 saw two military rebellions in which Chávez [a lieutenant colonel] participated. He created great expectations because he was seen as someone who took action against the government that many people rejected. This finally led to Chávez winning the 1998 presidential elections, amidst a lot of enthusiasm—but what he reflected was the social process of struggle and resistance against that political establishment.

There were expectations in two directions. The first was around democratic participation: there was a discourse around participatory democracy because representative democracy was bankrupt. And the second, around social justice, having policies to allow people who had been neglected and marginalized to gain access to this huge oil wealth that was seen as property of the state. But the problem was mainly seen as one of the distribution of the oil rent.

The impression that Venezuela has been a very rich country, where the issue is the mismanagement of wealth, is not correct, but these expectations were reflected in efforts to self-organize by the working class.

Hundreds of new unions were born in the first years of the Chavista government, amidst all sorts of community organizing efforts. It was a very exciting moment, indeed. Of course, the government, many of whose leaders came from the military, was ambivalent about this.

Many of the leaders of Chavismo had a very corporativist conception of power. They don’t really like people taking the initiative and organizing themselves. But really this contradiction between or inside the movement didn’t come to a resolution until the threat of counter-revolution or a coup was really defeated and it was left behind. [A mass popular uprising in defense of Chávez famously defeated a coup attempt in April 2002 – Eds.]

And this was quite clear when Chávez won the 2004 recall referendum and his reelection in 2006. It was around this time, six years into his government, that he started to talk about socialism, or “21st-century socialism”.

He decided to create the PSUV, as the official, unified party of Chavismo. So in a contradictory way, when Chávez started to talk about socialism, in concrete terms he was actually steering to the right, attacking independent unions and any form of autonomous organizing. When creating the PSUV in 2007, after several unions and leftist parties refused to join it, he went as far as calling trade union autonomy a “venom”

Then there was this Chávez’s ideology for development, based on fostering patriotic capitalists while dismissing the necessity of unions, alleging that rather than bargaining for wages, what workers needed was to participate in power. He tried to sell the illusion that workers would somehow be participating in power by being in the PSUV, by participating in the political process, but this was divorced from the concrete gains and the rights of the workers as such.

The process of creating the PSUV was really about putting under the control of the state the soul of the revolutionary process that started in 1989, well before Chávez came to power, which was [the] self-organization of the people and workers of the popular sectors.

Unfortunately, Chávez succeeded in really destroying this process, setting the grounds for his successor in government to reduce the value of real wages by over 90 percent, to destroy, intervene in or take over unions to jail or criminalize hundreds of union leaders and workers, without having to face a general strike or any real wide-spread resistance.

Because the resistance had been broken in those years, between 2007 and 2010, with the murder and jailing of many union leaders—persecution was already important. The main union, which was the National Workers Union, or UNT, became really divided and was left very weakened. In 2008, Chávez created this very corporative, pro-bosses union, which is the Socialist Bolivarian Workers’ Central [CBST].

This was the process for us after we participated in the struggle against the 2002 coup. José Bodas, an oil union leader, Secretary-General of the Federation of Oil Workers, was himself decorated by Chávez for his role in fighting against the 2002 oil workers’ lock-out. [A statement from Cde. Bodas is read during the full video presentation of this meeting, at 53:55 minutes. – Eds.]

So we all come from this experience fighting against the coup, [and] fighting against the right-wing, and trying to develop the experiences of self-organization of the working class and working people. It was really in that concrete experience that we came to the realization, [of] the need to break away from any sort of engagement with the government, because it was clear that it was a very anti-worker, anti-socialist government, despite its rhetoric. [It represented a betrayal of the social processes that started in 1989, with the popular anti-austerity uprising known as the Caracazo, and of the popular excitement and the massive support [for change from the] earliest stage from 1999 and 2000 up until approximately 2007, 2008. It was always a capitalist government, no doubt about that, but there was a shift to the right already under the Chávez government, which has continued to an impressive extent, unimaginable 10 years ago, under the Maduro government.

Under the Maduro government, constitutional guarantees have been suspended indefinitely since 2015. We have seen a massive use of paramilitary forces to attack popular protests in 2014 and 2017. This political crisis unfolded in the context of a deepening economic crisis, which obviously has also to do with the policies of the Chávez government during the oil boom, which was not taken advantage of, along with horrible mismanagement that followed.

EM: My dad always quotes Arturo Uslar Pietri when we talk about the oil boom, and about the oil wealth not being properly invested, or “sown”. What happened to what appeared to be very concrete gains, like for example this sort of mythological idea of Venezuela as the building site of a communal state? Where are these communes, and a popular, anti-imperialist militia, etc.? Or to the government’s hopes of inspiring a world revolution? What happened to those ideas?

SR: [On the “communal state” – Eds.] Well, it’s important when dealing with these discourses, to see the dimensions of things, because you could meet one co-operative or commune that functions well, say in the agricultural sector, with positive experiences. However, we have to look at the [whole, and the] scale of things.

You have to look into how the Venezuelan economy works,and then see how these small concrete experiences fit in the larger picture. Because then you can interpret what you are seeing. Otherwise, it’s very easy to be misled.

So in the case of the Venezuelan economy, you have to first look closer into this discourse around the nationalization of industries and enterprises that were taken over by the Venezuelan state. This wave of nationalizations started around the year 2007, 2008. But by 2014—and I take this year as a reference because it’s before the drop in oil prices, which really became like the last nail in the coffin for economic growth in Venezuela—the composition of the gross domestic product in Venezuela was 70 percent private and 30 percent state. And the sector of the economy of production that corresponded to co-operatives, all of these sectors of the so-called popular economy, comprise less than 1 percent of the Gross National Product, according to the official figures of the Venezuelan Central Bank. It’s not anything we make up. This is what the government said. And this was at the best moments before the onset of this horrible crisis.

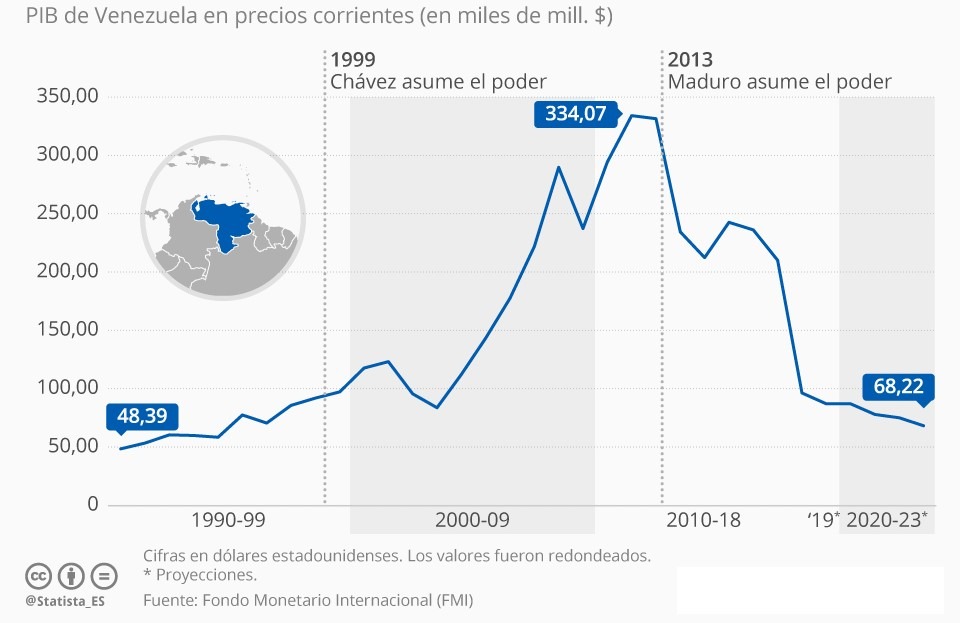

There is, of course, the idea that the crisis is solely or mainly the consequences of U.S. sanctions. But when you look at statistics on a time scale, what we are talking about becomes very clear. The first financial sanctions were imposed in 2017, and the first sanctions on the oil sector in 2019, but we have been in a major recession since 2013, well before the sanctions, suffering a hyper-inflation that has destroyed the wages of the working class, and find ourselves in a really, really horrible situation.

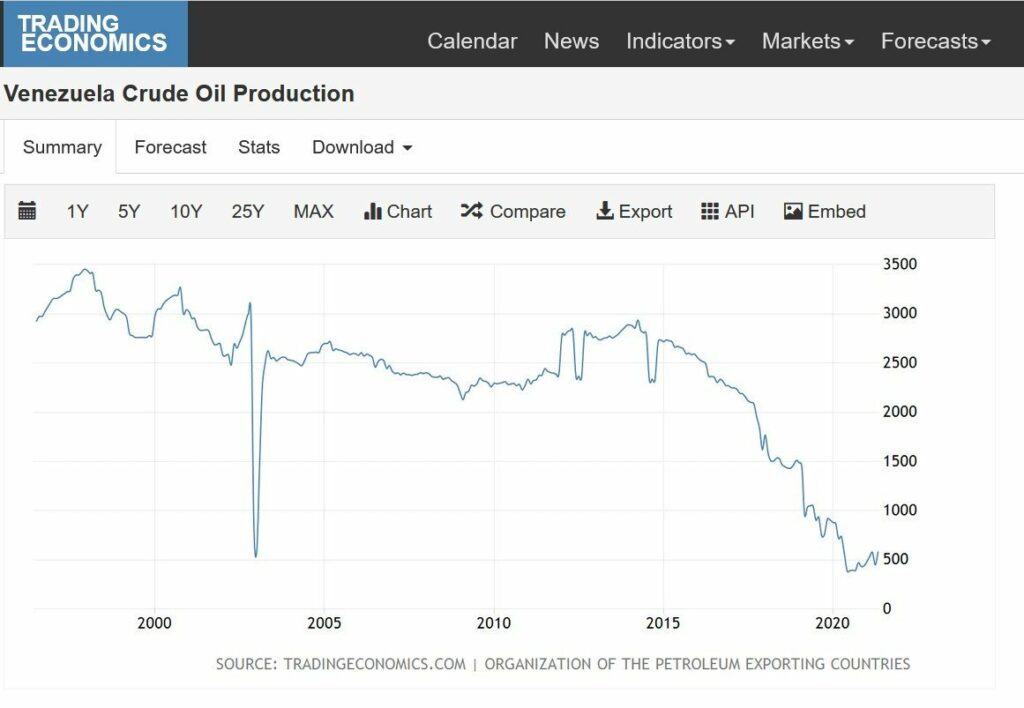

This graph [above, made from OPEC data] shows the production of oil over the last two decades or so. You see a first sharp drop around the first coup attempts in 2002, but then it stabilizes for almost ten years. We are reminding people that—at least until very recently when it was overtaken by gold and labor (remittances)— this was the country’s main export making up over 90 percent of its income from exports.

So it’s a crucial element of the Venezuelan economy. And we can see that production started to decline even before the financial sanctions and well before the oil sanctions, which accelerated the collapse. But oil workers had for years warned that lack of investment in the oil industry, corruption, and the looting of wealth through the model of joint ventures with transnational corporations like Chevron or Repsol, were affecting the capacity to produce oil.

Also, there was no plan for energy transition, or to confront the need to move away from fossil fuels. The Venezuelan government never invested in anything that remotely resembled a post-oil economy.

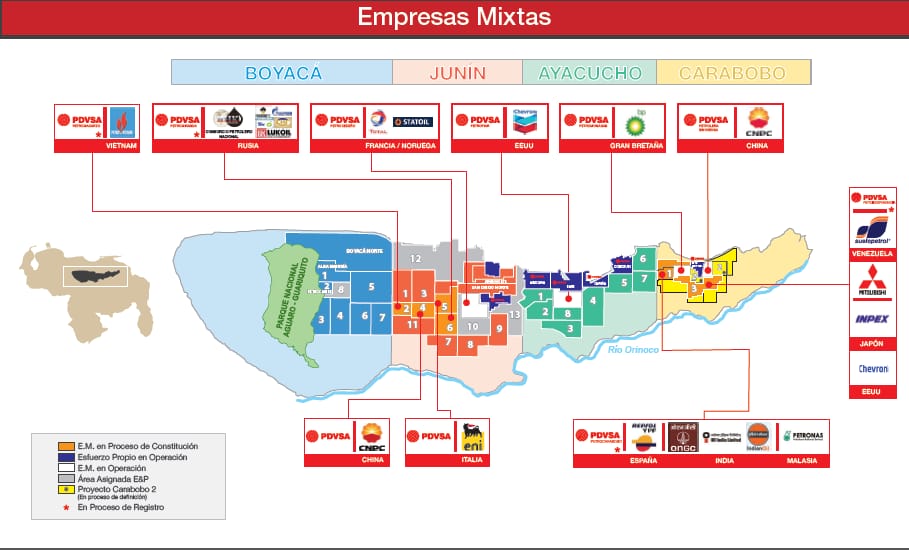

What we’re seeing now [above] is a map made by the state-owned oil company, PDVSA, where they show this part of the east of Venezuela, where they have what they call the Oil Belt and the multinational companies to which they assigned these oil fields, which make up the largest oil deposits in the world.

For Chavismo, this was simply an opportunity to become allied with these transnational capitals and in a form of privatization, to assign and divide [oil exploitation] up with transnational capital, which took 40% ownership stakes in these joint venture companies, and were able to claim ownership over the oil reserves in their accounts—going against the principle of State ownership of subsoil wealth.

This [above] is a part of that brochure by PDVSA. And it shows the oil fields with joint ventures, proclaiming with pride that it makes up over 40,000 square kilometers or 4 percent of the Venezuelan territory. Huge expanses, bigger than some countries even.

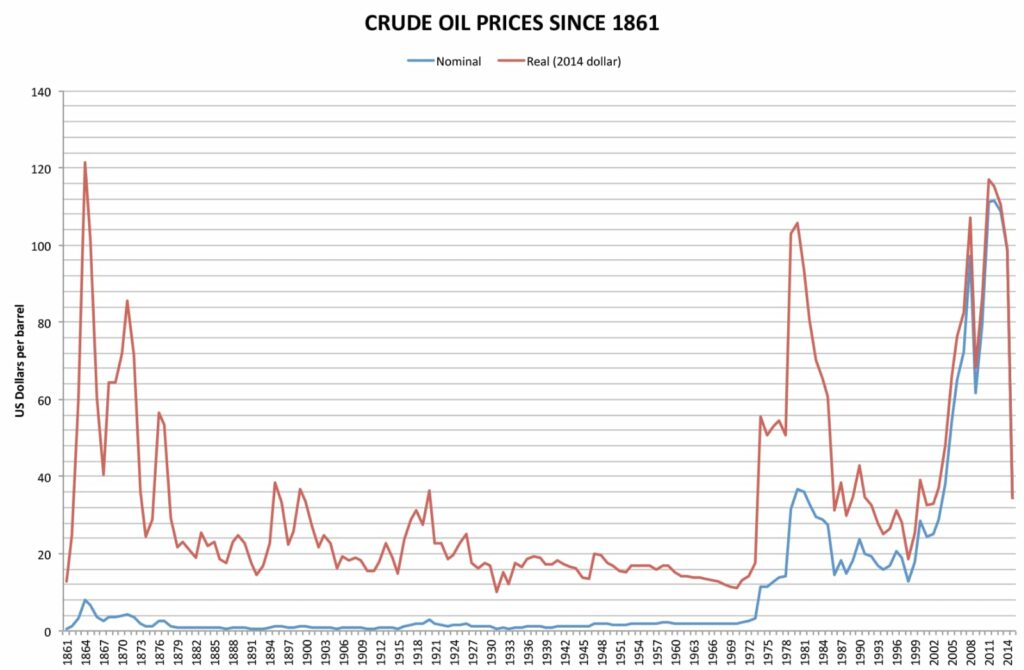

This [above] has been the crude oil prices since the 19th century and they are measured both in absolute prices and in relative prices. What this graph shows is that Chavismo managed the biggest and most prolonged oil boom in Venezuela’s history, and disposed of a huge income. So we need to ask what happened to that money. Why is Venezuela depending on food aid? Why do we need food from the World Food Program of the United Nations, if we once managed this huge amount of petrodollars?

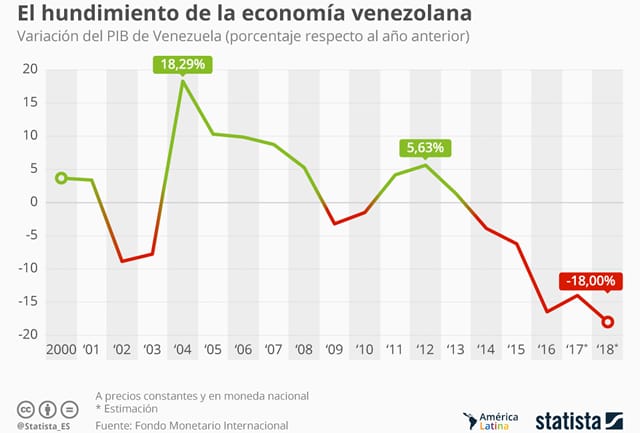

These two graphs [above], of annual GDP variation and the overall descent of GDP, show the year-to-year growth of the Venezuelan economy, and a very quick descent after 2013. It was falling long before the U.S. sanctions and even when the oil price was above a hundred dollars a barrel, something that never before had happened in Venezuela. Venezuela had always had cycles of prosperity, linked to the rise and fall of oil prices. But with Chavismo, we achieved something unique, which was to be in a crisis when oil prices were still very high.

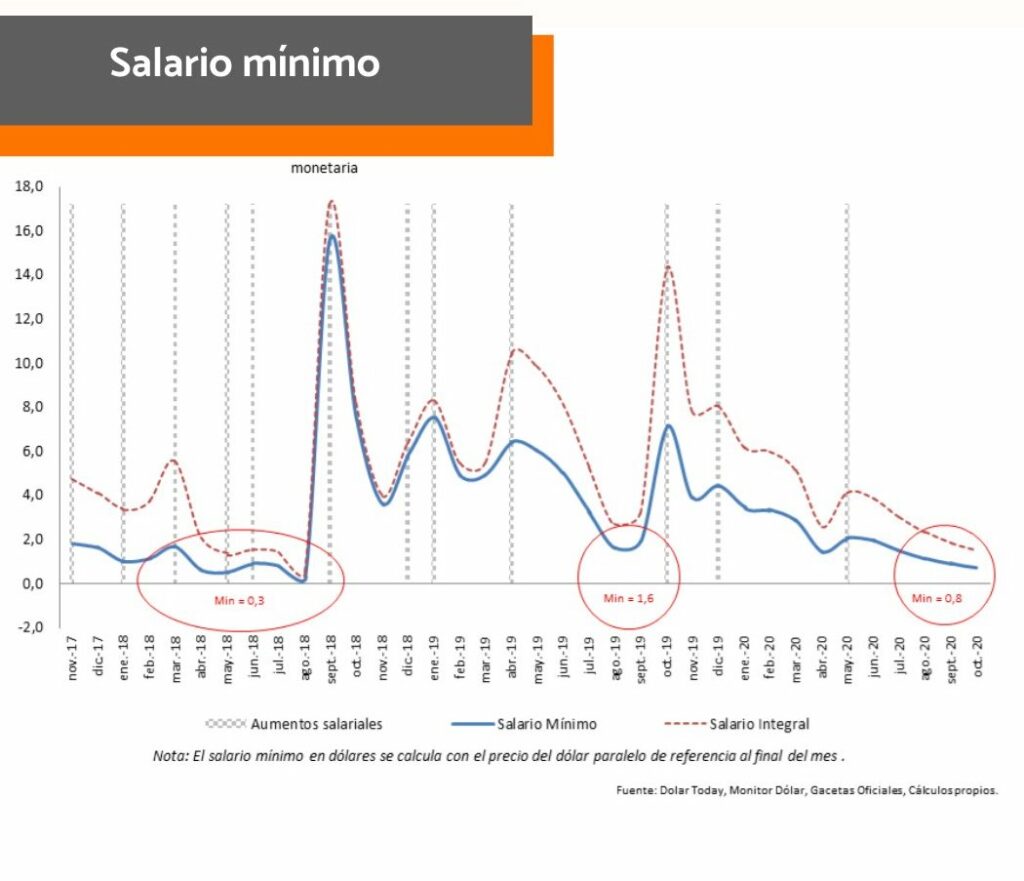

Lastly, [above] we can see how the monthly minimum wage has shrunk in a very drastic way, reaching a low of less than $1 in 2020. [Most Venezuelans can no longer subsist on the legally-determined wages but have to rely on arbitrary employer bonuses, family remittances, direct government or NGO aid, and informal labor to subsist.-Eds.]

What’s the rational explanation for all these phenomena? As the oil price was going up and the income of the government was going up, the government devised ways to loot the oil rent.

One was to have an artificially-low currency exchange rate. The government would allocate dollars [from oil sales abroad] to the private sector for imports, determining recipients, purposes, and amounts. This went to subsidizing imports rather than production in Venezuela. That’s the first problem.

But for private capital, receiving dollars that were so cheap meant there was no commercial margin that could beat the profits from re-selling their foreign currency assignments—it was almost free money. So what the capitalists—and Chavista bureaucrats—did was they falsified imports. They requested money for imports that they would then not make because the business revolved around getting the dollars. And this led to the huge capital flight of those years, the draining of the country’s wealth.

This was a wave of massive looting, carried out not only by Chavista bureaucrats and their Bolibourgeois cronies but also by the Opposition-linked traditional bourgeoisie and even transnational corporations.

General Motors, this huge multinational, received $13.4 billion from the U.S. government in the 2008 bail-out. But Venezuela, a third-world, semi-colonial country with poverty, with hunger, gave over $5.9 billion of subsidized petro-dollars to General Motors. [These funds would be used to purchase machinery and production inputs abroad and assemble the final product in Venezuela, transparently defeating the purpose of import substitution. As the final products would remain subsidized, it became impossible for national manufacturing to compete with imported goods in many fields.-Eds.]

Many other companies received a lot of these subsidized oil dollars, but when the assignments abruptly stopped in 2014, much of the imports and production simply stopped, triggering scarcity of consumer goods and hyper-inflation for which the government blamed a capitalist-led “economic war”, rather than admitting to its own drastic austerity measures.

Corporations like GM don’t produce anything in Venezuela anymore. The investments through this gigantic subsidy program were lost. Agricultural and infrastructural investments were also mostly abandoned. So many things that could have been done [with the 2000s oil windfall] and not only did Chavismo not do it—rather it engaged in the worst type of capitalism but it had the audacity to say it was building socialism.

So I think that you have to take this into account. The co-operative or communal sectors of the economy are very, very small. And it has also been used in a dishonest way. For example, state companies and institutions, rather than have unionized workers in their payrolls, started using cooperatives as a form of tercerización [outsourcing]. To externalize labor, you go to a co-operative because then that’s supposedly socialism and you can get the same things done but paying less, while laying off the workers that had the formal relationship with the company. This type of maneuver was very common in both state and municipal governments and the national one.

This doesn’t mean that there were no heroic efforts by workers and communities in cooperatives that are striving to survive in the midst of this huge and horrible crisis. They should be supported and have all our sympathy. But to think that the Venezuelan economy is based on cooperatives is to not see reality: gold mining and oil itself, even if [the national industry] is in ruins, remain the most important sectors of the economy.

[In Venezuela] commerce is mostly private and corporate . It’s important to see the scale of things, and I hope that this explanation into the economic process—showing that there was no break with capitalism, imperialism, or from semi-colonial dynamics—helps to explain what we are talking about when we say that this is a bourgeois reactionary government.

EM: What specific actions can we take from here in the U.S. in solidarity with the Venezuelan people? And more concretely, how can we best oppose U.S. sanctions? Do we oppose all of them, including ‘targeted sanctions’ on the government?

SR: Okay. First of all, we have to understand the nature of U.S. foreign policy— and we have no positive expectations of it. Because although the U.S. government traditionally says that they are for democracy, it has been the main force against democracy in Latin America and in other parts of the world, aiding dictatorships, and financing and providing logistical support for coup d’états.

And this is not only distant history, from the 20th century. We have the coup in Honduras in 2009, the coup in Haiti in 2004, among others. The latter led to the horrible crisis that continues to run, with the killing of Jovenel Moïse, the country’s de facto leader. Venezuela itself faced a coup in 2002, supported by George Bush.

So for the U.S., it seems very clear that it’s never about democracy. They have no problem with alliances to ruthless dictatorships, like Egypt or Saudi Arabia. They would have no problem with having a dictatorship in Venezuela if it was aligned with their interests.

We don’t expect anything from U.S. interference and would never call for it. We oppose both types of sanctions—those that affect the oil industry and the financial sanctions. The sanctions on the oil industry are the worst, given that the U.S. was our country’s main commercial partner and purchaser of oil. But there are other financial sanctions on companies that trade with Venezuela, affecting not only U.S. companies but also third parties.

These end up affecting mostly the Venezuelan working people, worsening a situation that was already calamitous. If an economic crisis were by itself enough to take down a government, then Chavismo would have lost power in 2014, but things are not automatic like that. So to try and worsen through sanctions what is already the worst economic crisis in the Western hemisphere is an irrational and very cruel thing.

The sanctions that freeze state assets, or those of individual bureaucrats, were used by the Trump government to confiscate funds which were then used for things like building the border wall with Mexico. This is literally piracy. In Venezuela, we have a saying that a thief that robs another thief gets 100 years of forgiveness—the U.S. government is stealing from a thief and thinking that it’s all right to do it. Well, it’s not, it’s still stealing from the Venezuelan people and we reject this as piracy.

When we’re finally able to restore some sort of democratic control, we should certainly wage actions for the recovery of these funds, or seek retaliation against the U.S. for not restoring stolen money or assets.

The other aspect of the sanctions relates to individuals keeping these fortunes in the U.S., Switzerland, Panama, and other tax havens. We would like to know who these people are, what amounts of money they have, what properties they have bought, the wealth they have amassed through corruption, but the U.S. government does not disclose this information because it uses it as a bargaining chip. They see an opportunity to sometimes blackmail these corrupt people, get them into negotiations to jump ship and so on.

And so their interest is not to make this public or to give back to the people what has been stolen from them. So the [sanctions] should all be opposed in a political sense because what the U.S. pursues is determining who rules in Venezuela.

There are a lot of things that can be done apart from rejecting the sanctions. I mean, for example, Chevron is paying hunger wages to Venezuelan oil workers. I’m sure it’s illegal in the U.S. for U.S. companies to engage in slavery or semi-slavery practices. The Left could raise a very strong voice in the U.S. against the super-exploitation of Venezuelan workers by Chevron or other U.S companies in alliance with the Venezuelan government. The same point could also be made for Norwegian, French, Spanish and Italian companies too.

Another very important aspect of solidarity is to demand the freedom of jailed workers, feminists, indigenous people, and to engage with ongoing campaigns in Venezuela, and fight them internationally. You could demand the freedom of Rodney Alvarez, a worker who has spent 10 years in jail for a crime he did not commit, just for struggling for union rights. Or that of Vanessa Rosales, a feminist who was detained, accused of helping a teenage rape victim to get an abortion, which is illegal in Venezuela. Or demand the freedom of oil workers who are criminalized for exposing corruption in Venezuela.

To demand that the truth be told about the victims of forced disappearance, like Alcedo Mora and the Vergel brothers and other people, activists from the left and from other sectors. Or demand the freedom of human rights defenders who are charged with manufactured accusations of terrorism.

These are very important things that should be and could be raised by revolutionary socialists, union activists, feminists, and so on in the U.S. and in other countries.

EM: What do independent socialist politics mean in Venezuela? What’s the state of the left opposition? What does PSL organizing work look like, or other grassroots organizing,? How many members are there? Are there independent candidates being presented by either PSL or other organized socialist organizations? And if so, like how many votes, what’s the influence of the left opposition in Venezuela?

SR: [Before going into the left opposition], it would be good to first differentiate between four sectors, broadly defined, that have their nuances and differences inside.

The first two are the sector that supports the Maduro government, and a sector that claims to be Chavista, and to be trying to continue the legacy of Chávez, but that is critical of Maduro, where you will have the Communist Party and some other left parties.

They do participate in electoral politics because although most of their legal representation was taken away by the government arbitrarily, they still have the possibility to have candidates through the Communist Party, which is the only one that was left standing by the courts. What the government does is it uses the courts to give the legal representation of parties to members that are aligned with the government, in a sort of confiscation of parties. There are also Chavistas, among them former ministers or high officials under Chávez, that think it’s important to build alliances with sectors of the right-wing opposition.

The right-wing opposition, the ones that believe that U.S. intervention is basically positive and rallies around Guaidó. They also have their divisions, some sectors more to the right, some more center-right.

If you wanted to see it more in a very broad sense, what the polls will tell you is that popular support for the government is around 10 to 15 percent, depending on the poll.

And then you people who define themselves as Chavistas, but do not necessarily identify with the Maduro government, Chavismo goes up to 30, 35 percent, and a similar number of people that identify with the Opposition. But then you would have almost half of the population that does not identify either with the government or with the right-wing opposition.So there’s a very important sector that strongly rejects traditional politics and is very disappointed with the traditional leaderships.

And finally, we have a left opposition that is non-parliamentary—anarchists, Marxists, trade unionists, researchers, feminists, anti-extractivists, and others—among which is our party, the Partido Socialismo y Libertad.

The left opposition has a social influence. For example, José Bodas, whose message we heard, he’s the secretary-general of the large, strategically important Oil Workers’ United Federation that represents more than 100,000 workers. There are bigger unions like the public employees’ union or the teachers’ union, but in the industrial sector, it’s the largest and the most influential. Trade unions are certainly one example of where left opposition politics open spaces for itself in the Venezuelan context.

Of course, we are not against united actions, especially in the unions. In the defense of democratic and workers’ rights, we often come together with critical Chavistas and independents.

Right now it’s very, very difficult to do electoral politics. Not only because of the narrowing number of legal parties [due to confiscations or bans] but also because of persecution. People who run as candidates can get fired from their jobs or face police persecution under false charges.

Even Chavistas are disciplined, and labeled counter-revolutionary for running independently] The government, for example, has been very strongly attacking the Communist Party— which is basically giving critical support to Maduro —because they don’t accept anything that is critical, even support they don’t accept. They were accusing the Communist Party of being financed by the CIA and of being at the service of imperialism. The most ridiculous fabrications were being directed at them. They responded in a declaration early this year when they said they fear that Maduro was sliding towards fascism. These are very strong words. This is what a sector of Chavismo itself is saying, not us.

Clientelism is very, very strong and very important in Venezuela. When you talk about the communes, about the government programs (misiones), the allocation of food and other subsidies is often used as a way to pressure people into political discipline, conditioning assistance on obeying and behaving properly.

The so-called communes are under the control of the Ministry of Communes, which decides whether it will recognize them or not. Given that they need government recognition or assistance, they do not have full autonomy and are thus seriously limited as sites for organizing struggles.

EM: Are there any words that you would like to close us with Simón?

SR: Thank you Eva and everyone who joined. We hope that this can spark new discussions and I’m always happy to attend any invitation to discuss informally or more formally with activists and people who want to know more.

I think that the link to the book was shared which is well, it’s something that we worked on. Also the Venezuelan Voices website, and the Venezuelan Workers Solidarity blog. I think if anyone wants to reach out with more questions or any invitations, the VWS email is a good way to contact us or follow us on social media.

So I will leave it at this. In the end, this is about building a real solidarity movement and bridges for internationalism, which are so really crucial for all of us. So thank you again.

Image credit: Tempest

Categories

We want to hear what you think. Contact us at editors@tempestmag.org. And if you've enjoyed what you've read, please consider donating to support our work:

DonateEva María View All

Eva María is a Venezuelan socialist feminist and anti-racist activist who lives in Boston and has written on Venezuela for Jacobin and Socialist Worker