No shortcuts on socialist electoral strategy

The case for the independent ballot

The socialist movement needs an electoral strategy that centers on building socialism independent of the Democratic Party. Although the number of self-described socialists elected to office has grown, this is not proof of socialism “winning,” as Emma Wilde Botta has argued.

Some groups within DSA, such as the Bread and Roses caucus, advocate the “dirty break” strategy—building socialist candidates and campaigns within the Democratic Party for a future break toward an independent socialist and/or workers’ party. Other socialists, including myself, argue that it is not possible for a genuine socialist candidate to run on the ballot line of a capitalist party. Consequently, building independent socialist ballots should be the exclusive tactic for socialist electoral strategy today over campaigns on the Democratic Party ballot.

Strategy and tactics in the socialist movement

Revolutionary socialists work to strengthen the independent political movement of the working class for its liberation and for the liberation of all. Elections highlight in concentrated form the political struggle among various social classes in society, and broadcast that struggle via news and media outlets. Accordingly, electoral politics is an important arena for socialists to reach broader groups of working people in order to organize more effectively and politically strengthen working class consciousness and organization. Sound socialist strategy necessitates working toward an independent socialist and/or workers party that maintains a political outlook consistent with workers’ revolutionary position in society.

On paper, dirty break and independent socialist ballot proponents share a similar strategy. Where dirty break and independent ballot proponents differ concerns tactics. Dirty break proponents argue for revolutionary socialists to run on the Democratic ballot line in order to build a stronger influence among working people. Once the socialist forces within the Democratic Party are strong enough, they can break from the Democrats and form a new party.

Part of the appeal of the dirty break is its proposal for how to project socialist politics without being blamed for “spoiling” the election by “taking” votes from the Democrats in close races. The epithet of “spoiler,” and the undemocratic system that supports it, has been employed to protect the left flank of the Democratic Party from political competition. Meanwhile, the Democratic Party has continued to shift to the right since the neoliberal boom of the late 1970s. However, not every election in the United States puts a third party candidate in the position of being a “spoiler.” Those who argue that socialists should run on the Democratic Party ballot line focus so much on the difficulties that they ignore the opportunities for independent ballots under the current system. Democratic Party-run cities and congressional districts where the U.S. working class is concentrated offer opportunities for socialists to challenge Democrats without fear of a Republican victory.

An independent socialist electoral campaign is best positioned to argue for more democratic elections. We can say clearly that the Democratic Party defends the undemocratic winner-take-all system because it is afraid of losing the political monopoly that it currently enjoys on the Left. Socialists can say, “Look, the Democrats are so afraid to run against us that they are not willing to make the electoral system more democratic. Instead, they run on the politics of fear to cajole workers to vote for them without offering them anything beyond platitudes. Meanwhile, they cave into the Republican right. If they don’t want socialists to “spoil” elections, they should support ranked-choice voting and proportional representation of political parties in all elections now, no exceptions.”

If socialists run in the Democratic Party, the tendency will be to dodge highlighting the undemocratic nature of U.S. elections in their campaign. After all, how undemocratic can the U.S. electoral system be if a socialist can so easily obtain ballot access as a Democrat?

For a socialist to run on the Democratic Party ballot line effectively, they will have to do the impossible—say that they are a socialist and criticize the Democratic Party every day of the campaign and every day in office. If they do not, the big “D” next to their name will consume and absorb their socialist politics. One example of this is that although Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has said that if she and Biden were living in another country they would not be in the same party, she did not speak out against Biden’s sexual assault of Tara Reade. Top strategists in the Democratic Party establishment who claimed to support the #MeToo movement not only refused to defend Tara Reade, but created a PR campaign to discredit Reade’s account against Biden. Of course, had AOC and others stood up for Reade, this would have severely strained their relations with the Democratic Party establishment and their primary goal of getting Biden elected. A socialist movement is worth nothing if it cannot stand with women against their abusers.

Bernie Sanders has challenged the Democratic Party establishment nominee twice in the presidential elections of 2016 and 2020. On both occasions, the Democratic Party undermined his campaign and manufactured victories for their preferred candidate. Instead of using this as proof that the Democratic Party was undemocratic and arguing that working people need a new party accountable to their interests, Sanders uncritically backed both Clinton and Biden. Herein lies a critical weakness of the dirty break strategy: how will a break ever occur in the future if its proponents support and withhold criticism of socialists who support Democratic establishment candidates?

By contrast, an independent socialist campaign does not face the pressure to downplay breaking from the Democratic Party. Instead, it raises the question of breaking from the party immediately,not at some distant point in the future. Independent socialist city councilmember Kshama Sawant argued for a “new party of, by, and for working people” during a speech at a campaign rally for Bernie Sanders in Washington state. She was able to do this because she is not in the Democratic Party and therefore not accountable to its interests. Interestingly, Jacobin editor—and supporter of the dirty break—Bhaskar Sunkara criticized Sawant for arguing for the formation of a new party, calling it an alien message within the Bernie campaign. In the end, the short term interest of winning Democratic Party campaigns overrides the long term political message that needs to be made: we need an independent party of the working class and we need to prepare for it in the short, and long term.

Furthermore, an independent socialist candidate does not have to bend over backward to distinguish themself from the Democratic Party. Their campaign is proof enough. This frees up the campaign to focus on how to project a socialist message. Sawant has shown that it is possible to challenge the Democratic Party from the left electorally since first elected in 2013. In 2019 she successfully defeated the multimillion dollar Amazon-sponsored Democratic campaign designed to unseat her, raising the profile of socialism nationally as independent of, and organizing against, the Democratic Party.

Will combining ballots build the independent socialist movement?

Eric Blanc, a key proponent of the dirty break, has argued that socialists should run campaigns on both independent and Democratic Party ballots to strengthen the socialist movement. On the surface, this is an appealing idea. Do those socialists who argue against the dirty break want to tie their hands by saying that under no circumstances should socialists run on a Democratic Party ballot line? Can it be said for sure that no socialist run on the Democratic Party ballot line could favor our side?

The desire to be tactically flexible is a healthy one. But, the questions posed above are not the central ones we face. They are abstract. The principle question is: what do we do today to build a socialist movement independent of the Democratic Party? In the context of a socialist movement that is growing and still struggling to form its own political identity, does it make sense to cede that identity by running on a Democratic Party ballot? Or would it be better to make modest steps toward building independent socialist ballots that do not depend on the Democratic Party to reach an audience within the movements and organizations in which we are rooted and building?

As illustrated above, the nature of running an independent socialist campaign and one in the Democratic Party are qualitatively different. Because socialist runs in the Democratic Party are advertised as easier to achieve and superior in terms of the broader audience obtained they will be favored over independent ballots. And, if used in combination with independent campaigns, will act as substitutes—or subordinate the independent ballot in order of importance—rather than function as a complementary set of tactics to build the independent ballot and movement. For example, NYC-DSA supported Cynthia Nixon’s Democratic Party primary run for governor in 2018 over the independent Green Party ballot of socialist Howie Hawkins. Even after Nixon’s primary loss to Andrew Cuomo, the NYC-DSA did not endorse Hawkins. Their support for Hawkins could have been part of building an independent socialist and working class ballot in NYC against an establishment Democrat.

Since then, the discussion among socialists supportive of using the Democratic ballot line has included no discussion of how to build independent ballots. There is a gravitational pull away from considering independent campaigns because they will interfere with Democratic Party campaigns that are perceived to be more effective in reaching an audience, a core justification for the dirty break. The idea of combining independent and Democratic Party lines is an approach to electoral strategy that, in practice, builds the Democratic Party ballot over the independent ballot.

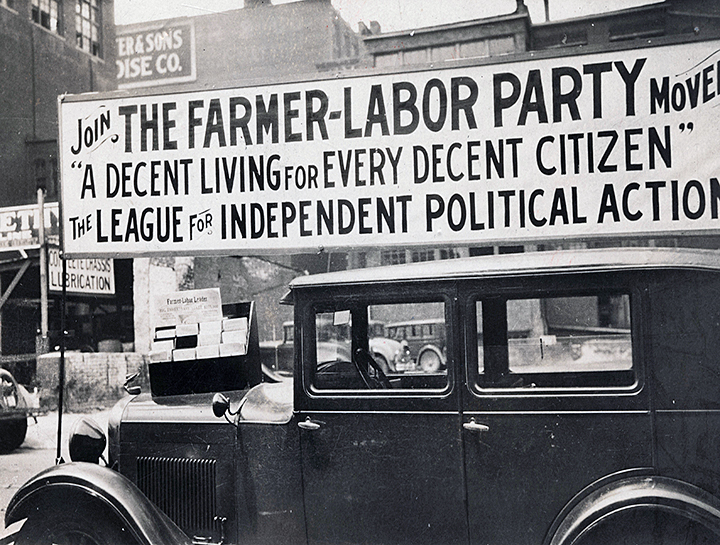

History provides an even more informative lesson regarding the obstacles to combining socialist/labor party and Democratic Party ballots. Socialist historian Mike Davis explains the failure of revolutionaries and the broader labor Left to build a third party of labor in the 1930s and 40s. Despite a considerable upsurge in labor struggle with the formation of the Congress of Industrial Organization (CIO), the Communist Party—the largest party of labor militants whose rank and file played a critical role in the upsurge—moved away from advocating a national labor party and shifted to political subservience to the Democratic Party. This missed the opportunity to expand on existing local attempts such as the Minnesota Farmer-Labor Party, the Wisconsin Progressive Party, and the Michigan Progressive Labor League. The smaller Socialist Party, while advocating independence from the Democratic Party, did not have a shared strategic perspective of forming a national independent labor party and building on the modest steps already taken.

These subjective considerations, combined with a bureaucratic offensive on the part of the AFL union bureaucracy and CIO collusion with the Democratic Party’s New Dealism, severely hampered the movement to build a national independent labor party. Fusion strategies that combined independent labor ballots with the Democratic Party only served the interests of the latter. David Dubinsky launched the American Labor Party (ALP) in New York with the intention of creating an independent pole of pressure outside of the Democratic Party. In practice, the ALP became a ballot line that siphoned votes from the Socialist Party. The Labor Non-Partisan League (LNPL) of 1936 and the CIO-PAC (Political Action Committee) of 1944 were ballot lines designed intentionally by those in the CIO bureaucracy to funnel labor votes away from independent labor party initiatives and to the Democratic Party. This failure to build an independent national labor party occurred in conditions of politically experienced socialist activists helping to shape the largest working class movement in U.S. history. What are our prospects in the relatively weaker position in which we find ourselves today? This history offers another cautionary tale: combining ballots will be a strategy the Democratic Party itself will employ to prevent an independent party from forming.

In the end, socialist campaigns on the Democratic Party ballot (even in cases where they are selectively used) sound good on paper and are devised with intentions to achieve political independence. In practice, they will not build the independent party or movement of the working class we need today.

Party ingredients: independent politics and a mass movement

What should be the strategic focus for socialists today? The view that elections are central to socialist activity (“electoralism”) downplays the struggle taking place in other parts of society and its role in shaping discussions and changing minds. No socialist electoral campaign could ever have achieved what the Black working class movement accomplished last summer, putting the question “should police exist?” front and center nationally with the demand to “defund the police.” Sanders—the nationwide reference point for socialism—did not support this demand. Individual DSA chapters participated in the struggle, but the organization as a whole struggled to form a national campaign in defense of the defund and abolition movement.

Of course, socialist criticism of electoralism should not be conflated with electoral strategy, as Emma Wilde Botta argues regarding DSA’s post 2020 election assessment. Rather, electoralism discounts the role mass movements and independence from the Democratic Party have had in the formation of third parties, even though the positive sample size is very small.

The Republican Party (with a critical push from the abolitionist movement) formed in the lead up to the Civil War, the greatest revolutionary movement in U.S. history. The Socialist Party formed out of the wreckage of the Populist movement of the 1890s and was strongest to the degree that it remained independent of Democratic Party liberalism and sustained itself by building a working class membership and supporting working class struggle. Even the example of the Minnesota Farmer-Labor Party, mentioned above and touted by Eric Blanc as a historical example of the dirty break, demonstrates the critical role a politically independent labor movement during the 1920s played in its formation.

If this cursory history provides any clue, we are more likely to see a revolution, or at least a mass movement of the working class, in this country before the formation of a socialist or workers party that is positioned to continually challenge both capitalist parties from the left. As long as there is no sustained independent movement of the working class in workplaces and communities around the country, no one will vote for an unknown socialist (or another left third party) candidate whom they will view as “spoilers.” Of course, this is not to argue that we should not advocate the formation of such a party. What it does mean is that we should not form one at all costs or pursue tactics that will entangle us in the Democratic Party as movements and struggle emerges. While Left third-party initiatives have a long and difficult history in the US, independent socialist electoral initiatives should not be ruled out, particularly given the current rise in the popularity of socialism.

On the one hand, the “dirty break” falls into the trap of seeking an easier, electoral route to build a party of the working class over the hard work the socialist movement will need to do to politically prepare for such a party. On the other hand, it ignores the centrality of mass struggle required to bring this party into being and fortify it.

Initiating a conversation about an independent socialist electoral strategy

Although elections are not an “end-all” for revolutionaries they are an important forum for winning influence in society, both during times of struggle and times when the movement is dormant. The fact that socialists do not have an independent presence in elections in the most developed capitalist nation in world history is a measure of weakness. The tasks for revolutionaries today are to build a broad socialist movement independent of the Democratic Party within communities and workplaces and look for opportunities to give electoral voice to those struggles from an independent position.

What are some concrete steps revolutionary socialists could take toward preparing an electoral strategy completely independent of the Democratic ballot when they make up a couple thousand people at most and the politics of socialism are growing, but still marginal to the lives of working people in the U.S.? In a discussion on the dirty break, Kim Moody concludes his contribution with some questions regarding what an independent socialist electoral approach could look like. Expanding on the questions Moody asks, here are some preliminary ideas:

- Where are the socialists? We need a survey of socialist (and other radical) groups nationwide in order to understand in which communities and workplaces socialists and radicals reside. This will inform the strategic orientation of the socialist movement in building extra-electoral struggle as a primary focus.

- How do we strike the balance between extra-electoral and electoral work? What are the issues the movement is taking up? Socialists within, and outside of DSA, along with other groups on the socialist (and non-socialist and radical) Left need to keep grass-roots organizing initiatives the priority in political work. Part of this work is initiating a conversation to determine the prospects for an independent socialist ballot that uses the campaign to highlight and build struggle in society. When the struggle is moving, the campaign should be propaganda for the struggle. When the struggle is in a lull, the campaign should be propaganda for the interests of the movement.

- In which types of elections should socialists run (city, municipal, state, federal)? Where should they run? Where is the system most vulnerable to socialist access? Let’s start where the Democrats have no challenge from the Republican Right. In which places are there large concentrations of working class people? We need to map out the U.S. electoral system with an assessment of the advantages and disadvantages of elections based on type, ease of access, scale of propaganda afforded with office, and the degree of working class composition of a locality.

- What are the assessments of socialists running for, and sometimes winning and maintaining office? What conclusions can we draw from the experience of Kshama Sawant in Seattle and Rosanna Rodriguez in Chicago for building independent socialist politics in those cities? How do we assess previous attempts by revolutionary socialists to build third parties historically? Although third party campaigns have not succeeded since the years of the Socialist Party over a century ago, how is the political terrain we face today different?

Conclusion

Joe Evica and Andy Serantinger provide ample documentation that in practice those advocating the dirty break are following a path that builds socialist opposition within the Democratic Party indefinitely. Their analysis exposes the underlying problem inherent in the strategy of running on the ballot line of a capitalist party.

In strategic terms, tactical runs on the Democratic Party ballot line today do not align with the strategy for working class political independence. Instead, the dirty break and ballot combination strategies, in their very justification and conception undermine confidence in building an independent socialist party of the working class and underestimate the political costs of running on the Democratic Party ballot during a time when the word “socialism” has more of a hearing than at any other time in the past century.

While Sanders and “the Squad” have given socialism a popular name in U.S. society, the 2020 elections are further confirmation that they remain a socialist opposition in a capitalist party with no exit strategy. They accept the discipline of the Democratic Party and encourage working class people to vote Democrat even though the party will be perpetually positioned to the right of where they stand.

When the Trumpian Right slanders Democrats for having the radical socialist Left in their midst and Left Democrats naturally deny this association or water down their socialist politics to be more palatable for the political middle, do we want to be voluntarily associated with this party through an electoral campaign? I don’t think we do. Instead, in the coming decades a clear revolutionary socialist message that exposes the Democrats for ceding ground to the Trumpian Right will best be amplified from a clear position of independence from the Democrats, electorally as well as in the grassroots struggle in workplaces and communities.

Categories

We want to hear what you think. Contact us at editors@tempestmag.org. And if you've enjoyed what you've read, please consider donating to support our work:

DonateNate Moore View All

Nate Moore is a public school teacher in Connecticut, a member of the Connecticut Education Association (CEA), and a member of the Tempest Collective.