An insidious dialectic

Anti-Semitism, Corbyn, and the fight for the Labour Party

AARON AMARAL: How do you assess the allegations of anti-Semitism within the Labour Party? For example, Momentum founder Jon Lansman claimed that anti-Semitism is a “wide-spread problem” within the Labour Party. Others have argued that Lansman overstates the case, and that anti-Semitism is limited to a minority within the party, in keeping with its appearance in society more generally. Does the issue exist within the Conservative Party, and if so why is the coverage so much less prominent for the Tories?

DAVID RENTON: It’s hard to be accurate about how widespread anti-Semitism is within Labour. We know that when asked something like a quarter of all British people admit to holding old style anti-Semitic thoughts. For example, ideas that Jewish people chase money more than other people. The proportion is not noticeably lower among Labour voters although it is much higher, as you’d expect among far right (specifically, United Kingdom Independence Party) voters.

Prior to Corbyn’s election, effectively no members were disciplined for anti-Semitic language; since then the number has increased dramatically and is presently standing at a rate equivalent to five hundred expulsions a year.

Many Corbyn supporters insist that it is wrong to infer from the increase that the problem has in fact grown. They tell you that complaints are being made and investigated factionally, that most or all of the behaviour about which people complain is really criticism of Israel. I have seen cases where suspensions were excessive (and were later withdrawn). I have not heard of any cases in the last year where an expulsion was so bad that those punished had any chance of overturning it in court. It seems to me that the people minimising the issue are not just wrong, they contribute to the difficulties faced by the Left.

The issue exists within the Conservative Party as well as Labour. In April 2019, Jacob Rees-Mogg, who is now the Tory Leader of the House of Commons, retweeted a speech by Alice Weidel, the leader of the German far right party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD). Six months later, Rees-Mogg claimed that Brexit was opposed by George Soros, calling him the “Remoaner funder-in-chief.” On the blog kept by Tory Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s special adviser Dominic Cummings, a recurring message has been that the British people have been falsely kept from enjoying the benefits of Brexit by a campaign run by the investment bank Goldman Sachs. Three times, Cummings has posted that Remain was funded by that bank, which was founded by Jews and is still widely perceived as a Jewish business. (It was a donor to the Remain camp, albeit a minor one.) In November 2019, Cummings warned that in the coming elections Remain supporters, “will cheat the rules, they will do anything, supported by the likes of Goldman Sachs writing the checks like they did in 2016.” Again, in the 2019 election, there were multiple reports of Conservative candidates sharing anti-Semitic tropes.

The center right press refuses to cover any of these stories, since they contradict its own narrative that anti-Semitism is only capable of existing on the Left. One story which did get some coverage was Jacob Rees-Mogg’s invocation of George Soros. Many people in Britain are aware of how in Hungary and elsewhere, Soros’ activities have been criticised out of any proportion to what he does, and he has become the embodiment of the Right’s fantasy of the all-powerful cosmopolitan Jew.

A key figure in the attack on Corbyn has been Stephen Pollard, the editor of The Jewish Chronicle, and a contributor to the Daily Mail and the Daily Express during the depths of their anti-refugee campaign in the early 2000s. Pollard sprang to Rees-Mogg’s defense, insisting that Rees-Mogg was no anti-Semite and protecting him from criticism.

AA: This past April, an internal Labour Party report (“The work of the Labour Party’s Governance and Legal Unit (GLU) in relation to anti-Semitism, 2014-2019”) was leaked. The findings seem to point to a systematic factional effort, by the right-wing of the Labour Party, to undermine and attack Corbyn’s leadership at every opportunity. The report seems to imply that Corbyn and his office made good faith efforts to ensure that allegations of anti-Semitism within the party were properly and expeditiously investigated and adjudicated, but that these efforts were undermined by party staffers, presumably sympathetic to the Labour Right. How should we understand this Labour Party report, in relation to the subsequent Equality and Human Rights Comission (EHRC) report, and in turn, Starmer’s actions against Corbyn?

DR: The GLU report shows that the Labour Right waged a factional war against Corbyn after he was elected leader and even after he came close to victory in the 2017 election. It shows that the people who opposed him diverted resources from campaigning, seemingly, to secure a Conservative electoral victory. It also shows that they had a particular hatred for Corbyn’s prominent Black supporters. They were dismissive of the promotion of one Black member of parliament, Dawn Butler, to the Shadow Cabinet. They wrote of Dianne Abbott MP that “Abbott is truly repulsive”, and that she “literally makes me sick.” Among officers working in the Labour compliance unit, precisely those charged with rooting out racism in the party, another Black MP Clive Lewis was described as “the biggest cunt out of the lot.”

Many Corbyn supporters took at face value the claims in the GLU report that the party had been serious about taking disciplinary action against members of the party; but had been frustrated by the Labour Right, who had deliberately sabotaged investigations with the intention of generating further negative press headlines against Corbyn.

Having read the allegations and counter-allegations (which are numerous and lengthy), the best we can say is this part of the GLU report is “not proved.”

There were occasions when the leadership office was lobbying for disciplinary action to be taken faster or further (for example, over Ken Livingstone), there were also occasions when it was lobbying for less to be done (for example, over Chris Williamson). When the leadership did press for action, this was generally in response to press demands—with parts of the Labour Left initially opposing action, the leadership coming under pressure, and then belatedly accepting the arguments for suspension or expulsion.

Part of how the EHRC dealt with the issue was to criticize the leadership for politicizing it by getting involved in disciplinary sanction. Their view was that Labour could and should have kept the issue separate from factional politics and that this required the leadership to leave investigators to get on with the task.

The press leaped on this criticism as proof that the leadership had got everything wrong, conveniently missing out their own role in pressing Corbyn to make the very decisions which the EHRC was now criticizing.

AA: More generally how do you assess Corbyn’s handling of the allegations of anti-Semitism in the Labour Party when he was party leader? Richard Seymour has argued that the Corbyn leadership’s biggest failure in addressing the allegations was to treat it “as a bureaucratic issue, with only bureaucratic solutions,” and that the leadership “didn’t even want to talk about the politics.” Do you agree?

DR: I agree the problem is political, but so do most other people on both the Left and the Right. The difficulty is in setting out what the politics were that Labour lacked.

My own view is that there were two main political gaps. First, a significant group of people around Corbyn, including the veteran leftists who formed his “kitchen cabinet” on the issue, did not really believe that anti-Semitism was capable of returning in Britain or that it could manifest itself on the Left. They were still fighting battles going back to the 1980s in which the Israeli state had weaponised false allegations of anti-Semitism as a mechanism to cover up its atrocities in Lebanon and elsewhere. These people might accept that Donald Trump facilitated a huge rise in global anti-Semitism in 2016, but they refuse to acknowledge that it can be articulated anywhere—including beyond the far right—once it has entered the political terrain. We had plenty of people in Britain whose core politics were footloose in the same way that has in the US led the likes of Jason Kessler or Cassandra Fairbanks to switch from being pro-Occupy to being white supremacists. Veteran activists took the view that so long as Constituency Labour Parties were free of anti-Semitism there was no real problem. But if your experience of the Labour Party was online, it was a different picture. Among those attracted to Corbyn were people influenced by conspiracy theories, second-camp anti-war politics, and the like. Behavior was much bleaker there—and the Left refused to see or confront it.

Second, in all his four years in the leadership Corbyn never set out the facts of the Israeli occupation or what the political and moral case is for Palestinian solidarity. It became a kind of shibboleth, an indicator that you were on the Left. Supporters waved Palestinian flags at Labour Party conferences. But—apart from at the party conference, where the politics was discussed—Corbyn relied on people coming into the Left already knowing and understanding the events of the Nakba, the history of Israeli incursions into Gaza, and so forth. People never seemed to understand that the more seriously you fight for Palestinian rights, the more you are likely to guard against anti-Semitic tropes, since any such conduct will inevitably be picked up by people who want the occupation to continue. Since 2018, there has been a general climate of censorship against Palestinian solidarity. If we had a chance to educate a generation of activists, that moment has now been lost.

AA: Much of the Left wholly dismiss the allegation of anti-Semitism in the Labour Party as a product of unprincipled attacks by the Labour Right. Even if we agree that the charges of anti-Semitism have been successfully weaponized—by the right-wing social democrats, liberals, Zionists, and establishment more generally—is there a danger to the Left in taking this position?

DR: You can’t weaponize something that isn’t there. The first major crisis for the Left around this issue came in Spring 2016 after Ken Livingstone’s crude and annoying remarks that Hitler had “supported Zionism” in 1932. Although it didn’t feel like this at the time, Livingstone’s intervention was, in retrospect, an opportunity for the Left. It was a chance for us to learn how much harm certain kinds of old leftist discourse was capable of doing. We needed to stop saying things which either were anti-Semitic or were borderline anti-Semitic (namely, the sorts of behavior which luxuriated in trolling British Jews, who are no more responsible for the state of Israel than I am or you are).

A significant minority of Corbyn supporters took the view that any criticism was exaggerated. They repeated the destructive behavior. Every time a line was crossed, they defended the perpetrator, calling them brave, anti-racist, and so on.

People in leadership roles on the Left—Chris Williamson MP, Jackie Walker, the Deputy leader of Momentum, and others—fell into the same trap repeatedly.

AA: Relatedly, sections of the Left, including elements around Corbyn (or Corbyn himself) have shown themselves inclined towards a type of campist, or what you have called “second camp” politics, which privilege supporting nation-states ostensibly aligned against U.S. imperialism (for example, Assad’s Syria) over solidarity with popular social movements. In the context of geopolitics in Southwest Asia in particular, this can lead to an overestimation of the role of Israel, or a so-called Israeli lobby, as a main danger. In your opinion, is there any convergence between this campist politics, and the understanding and treatment of the allegations of anti-Semitism? Or is this just a correlation that doesn’t have real explanatory weight?

DR: This is something I’ve written about in the case of Chris Williamson MP, that he received particular support from a certain milieu which had been pushed out of the main antiwar movement, precisely over its support for dictators.

With Corbyn himself the issue is more complicated. You have to bear in mind that the majority of criticisms directed at him personally relate to the period before he became leader. In office, he did surround himself with a number of people whose politics were second campist, but this wasn’t the only or perhaps the dominant feature of their politics; they were also trade union bureaucrats. And neither of those legacies were a good background in terms of getting them to understand the issue.

A number of the more minor incidents can be explained in terms of second camp politics: prominent Corbyn supporters sharing fantasies about the Israeli national intelligence agency (Mossad).

But one of the grimmest parts of the scandal was how little it had to do with Israel. If you think about the incidents which did most harm to the Left: Livingstone’s remarks on the Holocaust, Corbyn’s unreflective defense of a mural which on a second look was clearly anti-Semitic, Jackie Walker’s claims that Jews were the chief financiers of the slave trade, these weren’t the new anti-Semitism based on conspiracy theories about Israel. They were high-profile leftists saying negative things about Jews.

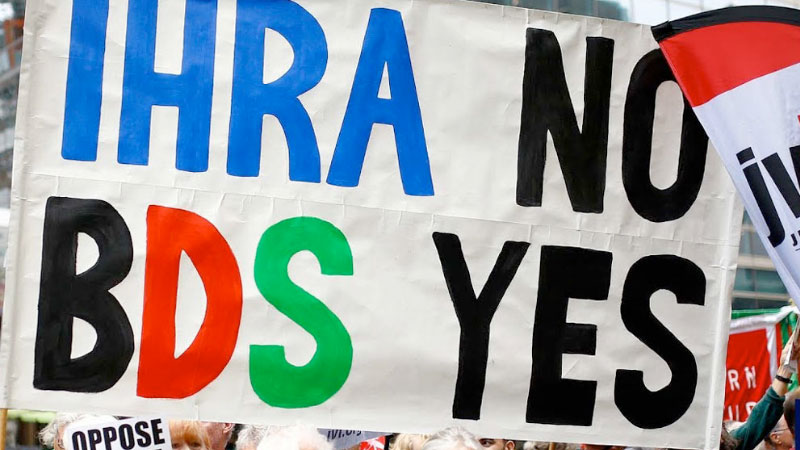

AA: In 2016, at the party conference, Leader Corbyn failed to get the following proposal adopted: “It cannot be considered racist to treat Israel like any other state or assess its conduct against the standards of international law. Nor should it be regarded as anti-Semitic to describe Israel, its policies or the circumstances around its foundation as racist because of their discriminatory impact, or to support another settlement of the Israel-Palestine conflict.” Rather, the Labour Party adopted, in full, a definition of anti-Semitism taken from the International Holocaust Rembrance Alliance (IHRA). It included, among other references to the Israeli state, this: “Denying the Jewish people their right to self-determination, for example, by claiming that the existence of a State of Israel is a racist endeavor.” Doesn’t this represent a concession to Zionism within the Labour Party?

DR: I supported Labour in rejecting the IHRA definition—as did a large majority of socialist lawyers and most leftists who commented on the issue.

The idea that it is offensive to complain that Israel is racist (for example, through state policies which exclude resident Palestinians from citizenship, but grant it as of right to non-resident Jews), seems to me to be based on the following logical steps:

- The Jews are a people;

- All peoples are entitled to their own state (“self-determination”);

- The present constitution of Israel is the only possible Jewish state imaginable, therefore any criticisms of its laws is to attack the very idea of a country where Jews might live freely (“a state of Israel”);

- All states are entitled to exclude whole groups of other people from citizenship on directly racial grounds;

- To restrict this right from Israel alone is to oppose Israel unfairly;

- And, because Israel is the state of the Jews, denying Jews alone the chance to exclude other people is to unfairly oppose Jews.

Almost nothing in the above set of assertions is compelling, step iv least of all. I do not believe that any state should be allowed to exclude whole groups of other people from citizenship on directly racial grounds. My own family were Holocaust survivors who escaped Europe in 1938. They came to a country which excluded people on grounds of ethnicity (“white Australia”): in consequence only some of them (my grandparents but not the generation above) were able to escape, and many died. Such ethnic exclusion always causes pain and suffering, and should always be fought: in Britain, the U.S., and everywhere. I find it unthinkable that such forms of ethnic exclusion should now be placed beyond criticism, on the grounds that to do so would be racist.

To say that criticising Israel’s Law of Return (or the treatment of the Palestinians which accompanies it) is prohibited—is not about opposing racism, it’s about defending and shielding racism from criticism.

Unfortunately, by late 2018 when this debate was taking place, Labour was seen as tainted and incapable of holding the line against the definition.

AA: In response to the EHRC report, Corbyn stated that anti-Semitism was “absolutely abhorrent” and “one anti-Semite is one too many” in the party. Yet he was suspended for then stating: “The scale of the problem was also dramatically overstated for political reasons by our opponents inside and outside the party, as well as by much of the media.” The implication from Labour Party leader, Keir Starmer, was that Corbyn’s statement itself was anti-Semitic, or a concession to anti-Semitism. Is this true? If not, is Starmer’s position a slippery slope in which any allegation of anti-Semitism that is raised is insulated from interrogation and defence? To what extent did the Labour Party adoption of the IHRA definition prepare the ground for Starmer’s stance and Corbyn’s suspension?

DR: The EHRC report made very little mention of the IHRA definition—a document which has no standing in United Kingdom (UK) law. Instead the EHRC drew on the UK statutory definition of harassment, which occurs when a person creates an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment for another person of grounds of sex, race, religion, and the like. Applying that definition, the EHRC held that denying reports of anti-Semitic behaviour can itself become a form of harassment.

The EHRC is not a large organisation; its team of full-time solicitors is about as large as the average high street firm. Most of its workload is policy not litigation. Few lawyers see the EHRC as a uniquely well-informed collection of specialists, but it has been easy to present them to the press as a gathering of the best anti-discrimination minds of their generation. Moreover, if we see referral to the EHRC as akin to a court process, it is in one important way different. When the EHRC criticised Corbyn and the Labour Party—neither he nor anyone mentioned in the report had any possibility of an appeal.

The authors of the EHRC report—who were in all likelihood relatively junior lawyers—appear not to have understood how section 26 of the Equality Act 2010 works. They quote section 26(1), which is part of the statutory definition, but not section 26(4) which limits harassment to behavior which has caused harm to a named person and where that person “reasonably” believes that it humiliated them.

Any lawyer of any standing could have explained to them the difference between the two following scenarios:

- A person makes a complaint that they have been the victim of racist behaviour. That complaint is upheld. Someone else hears about the incident later but denies it happened, doing so in a targeted, exaggerated and unpleasant fashion, likely to cause harm and distress to the original complaint. That would cross the line into harassment.

- Someone writes, as I have, words to the effect of, “the EHRC report is good on its own terms but the way it has been written tends to underestimate the problem of anti-Semitism in the Labour Party.” That is not harassment but is general political speech. It is not aimed at any one individual; it could not humiliate anyone. Swapping the word “overestimates” for “underestimates” does not make the sentence harassment.

Unfortunately, the EHRC report did pave the way for the treatment of Corbyn, and it will probably make other suspensions more likely.

AA: Should we understand Starmer’s suspension of Corbyn as a continuation of the war waged by the Labour Right that was highlighted in the March 2020 Labour Party report, and which was such a hallmark of Corbyn’s tenure as party leader? What are the lessons that revolutionaries should take in terms of their possible membership in the Labour Party?

DR: People need to put as much pressure as they can to demand Corbyn’s reinstatement. I have never believed in making a fetish out of membership of the Labour Party, or of any group on the British Left. You need to fight where you are. Moreover, it is part of the nature of the Labour Party that it is not merely a direct membership body, it also allows non-members to shape policy, for example, through union membership.

I would like to see members of trade unions demanding that their unions go on a “fees strike” (that is to say, withhold membership fees) until Corbyn is reinstated.

But I also know that, even while people take action, there’s a lesson to be learned about not tolerating anti-Semitic acts or speech. The Left needs to be much sharper and stop gifting the Right easy opportunities to attack us.

We want to hear what you think. Contact us at editors@tempestmag.org. And if you've enjoyed what you've read, please consider donating to support our work:

DonateAaron Amaral View All

Aaron Amaral is a member of the Tempest Collective and serves on the editorial board of New Politics.