21st century noir in ‘50s Detroit

A review of Soderbergh’s No Sudden Move

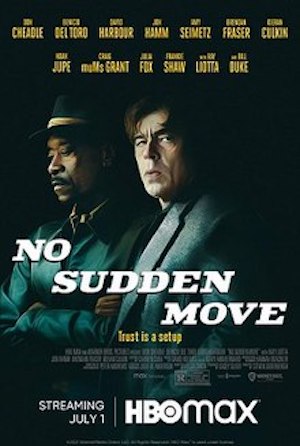

No Sudden Move

by Steven Soderbergh, Director

Warner Bros. , 2021

Since everything is available streaming now, and very few people watched it when it came out, I feel like No Sudden Move, a 2021 film released by Steven Soderbergh on HBO, is fair game for a review. Especially since it’s a wonderful movie which is profoundly political.

–Glenn Allen

No Sudden Move (hereafter “Move”) is visually stunning in a low-key manner, with exceptional performances from a gifted cast. It also manages to be an indictment of capitalism without being didactic. It is unfortunate that it was released almost without notice; more people should see it.

Move opens with a lone man walking through an industrial area at sunup. He continues to walk, past factories and houses in what we will learn is 1950s Detroit. He has a long way to go, does not have a car, and needs to be somewhere early. We also learn that he is Black (played by Don Cheadle), neatly dressed, and does not want to be recognized. Also, everything on screen is different shades of blue. This makes sense within the scene as it is early morning. But everything will continue to be largely shades of blue, or largely shades of yellow. It is 30 minutes into the film before red is introduced to the palette in an especially dramatic scene. As in many of Soderbergh’s films, Move has a complicated visual language involving shades of color which subtly affects the tone of a scene.

Move is an update of a film noir. It is full of double and triple crosses, with a femme fatale and several suitcases full of money. Cheadle plays Curt Goynes, a man just released from prison who needs money fast. He is hired along with Ronald Russo (Benicio Del Toro) to do a simple job for a suspiciously large amount of money. The job very rapidly becomes very “not simple.” As they track down a mysterious set of documents, we learn that both men have a bounty on their heads, and both are trying to leave town for different reasons. Through a series of ‘moves’ (as referred to in the title), Goynes enlists underworld allies and finds that auto executives are willing to pay an ever-increasing amount of money for the documents after they are tracked down.

The cast of the film is outstanding. David Harbour (the sheriff from Stranger Things) is unrecognizable as an ineffective accountant who is pointedly less competent than the women in his life. Brendan Frasier is wonderful as a mid-level mobster. Jon Hamm plays a clued-in detective who is completely scrupulous about his employer’s money, but completely unconcerned about human life. Ray Liotta has one of his last performances as mob leader Frank Capelli. And there is also an uncredited Matt Damon playing the epitome of a ruling-class executive—all privilege and scornful confidence, with a show-stopping monologue on the nature of capitalist power and wealth.

As is all too common, this is a male-centered movie. The protagonists are all men and most of the scenes involve exclusively male actors. All of the well-known actors are men. That said, the female cast is extremely strong, and they are given roles that exceed women’s parts in most mainstream movies. They are all pointedly more decisive and capable than their male counterparts. Women have extended conversations about things other than men, on more than one occasion. Admittedly, this is a very low standard to meet, and there is no reason other than screenwriting tropes that the female characters couldn’t have more screen time. Soderbergh has made other movies with women as leads—Erin Brockovich for example, and the under-appreciated Haywire (basically a remake of the first Bourne movie but with a female super-spy). Amy Seimetz is a standout as the cool, confident wife of David Harbour’s accountant, and has one of the best scenes in the movie. Julia Fox and Frankie Shaw are Russo’s and Wertz’s mistresses respectively—there are a number of mistresses in this movie. Any of these actors could have been more integrated into the plot. All of these actors have been working for some time in little seen films, and deserve more.

Race permeates this film. The backdrop of the movie is 1950s Detroit, with the expansion of the auto industry. There is a quick discussion of ‘urban renewal’ – in this case, the construction of Interstate 75 which displaced a prosperous Black neighborhood. Goynes is looking for a relatively small sum of money to buy back the family home in Kansas City. While it’s never stated explicitly, it’s safe to assume that the house was lost due to a red-lining scam. Russo is quickly shown to be an extreme racist, to the point that other white men find him annoying and ridiculous. However, unlike in The Defiant Ones, or the more recent The Green Book, the men do not grudgingly become fast friends. They do form an uneasy alliance, largely because Goynes is clearly much more competent than Russo.

Soderbergh has made many noir/crime movies – The Underneath (a remake of the classic Criss Cross), Out of Sight, The Limey, not to mention his non-noir heist series Ocean’s Eleven through Ocean’s Thirteen. But like most film noir, their casts are largely white. Here, the protagonist of Move is a Black man, and this changes the nature of the story. Film noir—simply put, a genre of stylized detective or crime movies from the 1940s and 1950s typically reflective of the social and political anxieties of the period—rarely had Black characters. In those that did they would be extras or secondary characters, such as Sidney Poitier in No Way Out. Many of these movies were made by leftists, and at the time casting Black actors playing train-porters or parking lot attendants were considered progressive, a change from the exclusively southern rural Black farm-hands or maids in other mainstream Hollywood movies.

You have to look to the late-1960s blacksploitation film explosion to see Black actors in lead roles in crime movies (or, with the exception of Sidney Poitier, any movies). And this change made a fundamental difference in these movies. For example, 1972’s Superfly is the story of a gentleman criminal who needs to make one last big score before he can get out of the business forever. This is a very common plot in crime movies. But Priest (the protagonist of Superfly) has to deal with racist mobsters, racist police, and what his future prospects are as a Black man in the United States. Race necessarily becomes central to the movie.

Alfred Hitchcock and the people around him coined a term for the object in a movie that occupies the character’s attention and moves the plot forward – they called it a MacGuffin. The point was that it didn’t matter what the specific object was – the microfilm in Hitchcock’s North by Northwest, R2D2 in the original Star Wars, the suitcase in Pulp Fiction or the Infinity Stones in the Marvel movies. Move has a MacGuffin, the documents mentioned above. This MacGuffin continues to be a generic object—they are technical blueprints that the protagonists actually can’t decipher until the last 15 minutes of the film. At this point it suddenly becomes a very specific thing, part of a real-life conspiracy that gets to the rotten core of capitalism. It is also an extremely self-aware gesture that plays on traditional film storytelling.

Try and obtain a pass to HBO Max to check it out – while you are there you can watch the excellent updated Watchman series, or the Suicide Squad (the 2021 movie, not the 2016 trainwreck) spin-offPeacemaker, which has a surprising anti-fascist sub-plot. Maybe for others to review?

Featured Image Credit: Don Cheadle, No Sudden Move, Warner Bros., modified by Tempest.

Categories

We want to hear what you think. Contact us at editors@tempestmag.org.

Glenn Allen View All

Glenn Allen is a long-time political activist in Chicago.