Reflections on Emily the Criminal

A film review

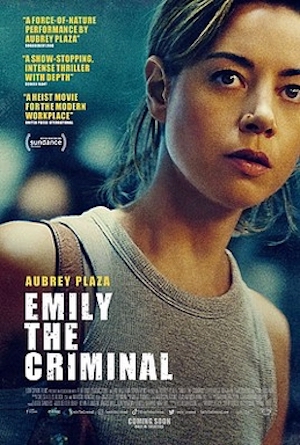

Emily the Criminal

by John Patton Ford

Vertical Entertainment/Roadside Attractions, 2022

Emily the Criminal is a movie worth seeing. It addresses, in a realist style, the issue of crime from the standpoint of the criminal herself, her situation, and her experiences. It avoids the twin dangers of arrogant and self-righteous moralizing or romanticizing the world of crime. Notorious examples of this latter tendency populate popular culture of the last several decades, like the Godfather series and The Sopranos, which naturalize and even glorify the socially parasitical and murderous Mafia.

Early in the film, we are introduced to Emily (played by Aubrey Plaza), the key figure in the film. Emily is a young, working-class woman and a college dropout with artistic inclinations who works in a low-paid food-service job. Emily lives in a modest apartment in a poor neighborhood that she shares with an Asian immigrant family.

Tough and ambitious, she is constantly trying to escape the drudgery of her job, her debt, and her poor living conditions by finding a meaningful job with better pay, so she can also continue to help her sick mother. But that possibility is closed off by a criminal record for assault, as well as by the chicanery of her potential employers whom she refuses to accommodate. In one interview for an ostensibly promising position working alongside an Black woman friend from her college days, Emily is told by the boss (a white woman) interviewing her that the desired position involves a long internship without pay, a requirement that Emily can neither afford nor tolerate without losing her self-respect and dignity. As the viewer, already familiar with her personality, can expect, Emily angrily walks away from the humiliating interview.

As Emiily is desperate to find a way out, a fellow worker puts her in touch with a small group active in the business of credit card fraud. Her two bosses—poor Arab immigrants seeking, like her, to “make it” for themselves and their families—fabricate fake plastic credit cards. They give these to Emily and her fellow “dummy shoppers” to shop with at different venues and then turn over the “bought” merchandise to them in exchange for pay. As Emily progresses with her assignments, she is given bigger, harder, and riskier jobs, with correspondingly higher remuneration. In one of her last assignments, she is tasked with buying an expensive car, a job for which she is expecting to be handsomely paid. Unfortunately for her, the car dealer quickly finds out that her card is fraudulent. Emily manages to steal the car, but not before the car dealer catches up with her with just enough time to hit her hard in the face through the car’s open window.

This confrontation forces Emily into becoming aware of one of the fundamental realities of the business she is involved with: that it is a violent world. The more she gets involved in the fraud business, the more violence she encounters, not only coming from her victims or intended victims when they discover they have been “had” by her, but also from the latent violence that inheres in the criminal world itself, generally devoid of mechanisms to mediate or arbitrate conflict among its members. And it is the explosion of that latent violence between the two heads of the scam organization that comes close to undoing her. One of the two bosses—with whom she develops a sexual relationship—is robbed by his partner. Encapsulating the nature of the relationships in that world with the memorable line, “He robbed me before I could rob him,” he gives Emily the bad, but expected, news, and recruits her to partake in a heist against his partner to get his money back. But the first boss ends up being shot by the partner, who leaves him to die on the street. Emily is forced to run away. She is next seen in the final scene set in an indistinct town by an indistinct beach in a Spanish-speaking country, heading her own small fraudulent credit card business, and training her future fake-credit-card junior partners based on the same instructions and warnings she received when she started out in the business in the U.S.

The Emily of this film is clearly treated with a sympathetic eye. She is presented as an oppressed and exploited working person who, burdened with student debt and a sick mother to support, has been forced to engage in crime by the gross injustice of having a criminal record that prevents her from getting a decent job. She is, in other words, an unwilling victim of the built-in exploitative inequalities of the economic system. Like many so-called delinquents, she does not start as a hardened criminal committed to crime. To quite the contrary, she is shown holding on to her food service job for quite a while after she starts out on the fake credit card business, “casually, intermittently, and transiently immersed in a pattern of illegal action” (28), as the late Berkeley sociologist David Matza describes many delinquents in his Delinquency and Drift. Yet, no matter how tough she is and how feistily she attempts to fight her way out of victimhood, she ends up being caught by an unforgiving system.

The feeling and concern that Emily awakens are reinforced by the nature of the crime she is involved with, victimless crime. The victims of her credit card scam are overwhelmingly large businesses, not individuals, and certainly not poor and vulnerable people. Businesspeople may claim that the scams are not victimless, since they considerably increase the business’ insurance and other costs, which inevitably end up being passed on to the consumers in the form of higher prices, which especially affect the poor. However, this argument misses the point that, unlike robbery and various types of white-collar crime–like real estate redlining–that directly victimize persons, often poor and vulnerable, in sudden, shocking and unexpected ways, the consequences of a victimless crime like credit card fraud are typically spread among and endured by a far larger number of people over time, and thus have a significantly smaller and much less frightening and shocking effect on them.

At a gut level, however, it is the motivation behind her breaking of the law that allows the film to decidedly side with her, namely the basic human notion analogous to what in Roman law was called furtum famelicus—theft motivated by hunger—based on the notion of necessitas non habet legem—necessity has no law, a maxim meaning that the violation of a law may be excused by necessity. It is a notion that Victor Hugo brings back to life in his Les Miserables, with the figure of Jean Valjean, a man who was condemned to prison for having stolen a loaf of bread and who must remain on the run after he escapes from jail to avoid the obsessive efforts of Inspector Javert to return him to prison. Javert is an unforgiving representative of the law, unable to recognize the human and social context in which law and order tries to impose itself.

In the end, however, contrary to the romantic notion that sees crime as a form of resistance to oppression and exploitation, Emily the Criminal shows Emily adjusting to the system by becoming a full-time small businesswoman running an illegal credit card business and reproducing the relationships of the criminal world she joined by recruiting and training others in crime. Rather than opposing or resisting the system and changing the conditions that led her to the world of crime, she has built what Raymond Williams, the British cultural historian, described as an “alternative” way of life within capitalist society, similar, in some important structural respects, to the bohemian and other “deviant” communities that find a niche to exist and survive inside the system instead of attempting to resist it and change it. That is a far cry from resistance and opposition, like the one embodied by Malcolm X, for example, who came from far worse conditions than Emily’s, including a long stint in prison. Malcolm tried not only to survive as Emily does, but also to reflect on the circumstances that led him to a law-breaking life. This reflection commits him to a project of change, emancipation, and liberation. He did so without looking down on Black people who continued to live the way he used to. He wanted to win over those sisters and brothers to a better way, socially as well as politically, not to condemn them from on high. The character Emily is a fighter, but her horizons are limited to her own survival within the system.

Featured Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons; modified by Tempest.

We want to hear what you think. Contact us at editors@tempestmag.org.

Samuel Farber View All

Samuel Farber was born and raised in Cuba and has written numerous articles and books about that country as well as on the Russian Revolution and American politics. He is a retired professor from CUNY (City University of New York) and resides in that city.