Resisting the backlash

Tempest panel to defend Black studies

In an era when a right-wing backlash against the Black Lives Matter movement, when teaching the truth is illegal, and when both the far-right and liberals are conceding to the logic of sacrificing the narrative of oppression and struggle with a comfortable multiculturalism, how can we fight back? Our speakers look to organizing among educators, participating in the June 10th National Day of Action to Defend Truth, and building labor movements in higher education as inspiring sites of struggle.

Kristen Godfrey: Thank you for coming to this event titled “Resisting the Backlash, Defending Black Studies.” It’s a very important conversation to have today when we’re connecting with other struggles and fighting back.

We have three excellent speakers today. Donna Murch cannot join us today, but we’ve got Phil Gasper, who will give an excellent talk and a shout out to Rutgers for all the work Donna and the union are doing there.

A little bit about Tempest: We aim to create a space for the Left to come together and discuss and debate. Our goal is to put forward a revolutionary vision that is clear and understandable, that weighs in on strategic and tactical questions, offers concrete guidance as well as political theory, and presents a consistent set of working-class politics from below.

We’re a membership-based organization with chapters in Chicago, LA, New York, and throughout the United States. And you can learn more about us at tempestmag.org.

We’d like to give a shout out to the National Educators United for supporting this event today.

When I went to undergrad in Tucson, Arizona they actually successfully fought to get rid of ethnic studies by the evil Ben Shapiro. And then in graduate school I went to the University of Tennessee. It kind of followed me. And there, the state legislature voted to get rid of the Office of Diversity and Inclusion successfully. This isn’t new, but it’s happening to us.

Florida Governor Ron DeSantis is really trying to bring this home. He and the Republican Party have launched a reactionary attack on Black studies and discussions of race and racism in schools, colleges, and universities.

This attack has led to book bans and curriculum restrictions around the country, not just Florida. But students, parents, librarians, educators, activists, organizers are not taking this lying down and are organizing to oppose this censorship. This discussion will examine the reasons for the backlash against Black studies and how we can defeat it.

Our first speaker is Jesse Hagopian, who is an ethnic studies teacher at Garfield High School in Seattle. He is a member of Black Lives Matter at School, the National Steering Committee, and co-editor of Black Lives Matter at School. He also organizes with the Zinn Education Project.

Second, we’ll hear from Daniel HoSang. Daniel teaches ethnicity, race and migration in American Studies at Yale University, and is the author of a Wider Type of Freedom: How Struggles for Racial Justice Liberate Everyone.

Finally, we’ll have Phil Gasper. Phil is a socialist and anti-racist activist who has worked in higher education for over forty years. He is currently a faculty member and a member of AFT Local 243 at Madison College in Wisconsin. Phil is co-editor of the Independent Socialist Journal and New Politics and a member of the Tempest Collective.

Jesse Hagopian: I’m sending my solidarity to the Rutgers faculty in the struggle. I want to begin today by telling you about my recent visit to a school in Florida. I’m an organizer with the Zinn Education Project, helping to lead the Teaching for Black Lives Campaign, and I had the opportunity to join a class in Florida following the screening of the new film, The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks. I will not divulge which school the event happened at, because in these dangerous times it could potentially put the educators at risk.

We are living in an era when teaching the truth about racism has been made illegal. These history deniers, in the same breath they use to decry cancel culture, and without even blushing, will call for the canceling of any book or any educator that diverges from the orthodoxy of American exceptionalism.

So perhaps I don’t need to persuade you all here today that something is profoundly wrong with our society. It is so terrified of its past that it endeavors to strangle history, dump its corpse in a casket, bury it beneath the earth, and not even leave an epitaph that would allow young people to recognize it had ever existed.

So about that school in Florida, I will tell you that it was a high school and that the multiracial group of students really loved that film about Rosa Parks. They were upset that this was the first time they were learning truthful accounts of Mrs. Parks’ life, about her struggles for social justice, including fights against sexual assault, against police violence in the North, against South African apartheid and war, and so many other things that have been hidden from them.

The urgency of students learning the truth about Rosa Parks’ life was recently spotlighted in an investigative report by The New York Times, which found that the company Studies Weekly, which produces a widely-used curriculum that reaches at least 45 thousand schools in the country. Studies Weekly inflicted a particularly vicious form of what Professor Henry Giroux calls the “violence of organized forgetting” with regard to Rosa Parks’s life.

As in the vast majority of textbooks in this country, Studies Weekly reduced Parks’s life to her arrest on the bus in Montgomery, Alabama, which is the quotidian, normal, standard procedure in American textbooks. But what made the Studies Weekly curriculum remarkable was that it proposed a revision to that telling of Parks’ life that read like this:

“Rosa Parks showed courage. One day she rode the bus. She was told to move to a different seat. She did not. She did what she believed was right.”

Now, if you’ll notice, there’s no discussion of the fact that she’s Black and that she was arrested for being Black and not giving her seat to a white man. And that segregation existed, that it was real, and that it was racist. All discussion of race was pulled out of fear of the laws in Florida.

So after some discussion of this film with the students in Florida, I asked what they thought of Florida’s so-called “Stop Woke” Act, the bill that restricts the way public schools can teach about racism in an effort to ensure that white people don’t experience feelings of discomfort. And one of the students quickly raised her hand. When I called on her, she made it plain. She said, “It’s wrong to erase Black history. It’s part of American history.”

This is what’s going on in our schools today. In a survey by the Zinn Education Project, a Florida social studies educator recently explained the sentiments of many teachers about these educational gag orders. “It is creating a chilling effect on education. We continue to teach the truth, but with much less certainty what the consequences will be for doing so.”

Another teacher reported to the Zinn Education Project, “I’m terrified to say anything about enslavement because it might make students uncomfortable. I also can’t recommend any

And that’s not hyperbole.

Florida passed a law that says that teachers who are caught with the wrong books in their classrooms, books about issues of race and gender or sexuality, are risking up to five years in prison and a $5,000 fine, which carries with it a third-degree felony. Florida is one of 18 states that has passed laws to mandate that educators lie to students about structural racism, sexism, and heterosexism. Many local school districts across the country, the North and the South, blue states and red states, have passed similar laws.

ln addition, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis signed the “don’t say gay” bill, making Florida one of at least six states that censor discussions of LGBTQ people and issues.

In addition to banning books, Florida, as you probably know, banned the College Board’s newly-created AP African American Studies class. As bad as it was that Florida banned Black studies, the deeper problem was that the College Board caved to DeSantis’s critiques of the course and went on to deliver a masterclass in irony by deleting the word “systemic” from the curriculum to describe racism in the U.S.

I would suggest to all the educators here today that if you want to teach about what systemic racism is, you only have to teach the story of the College Board deleting the words “systemic racism” from their curriculum. Professor Joshua Myers from Howard, who had helped develop the original AP curriculum that had systemic racism in it, said, “This was pure cowardice, and it shows how far liberals will go to confront the creeping fascism in this country. And that’s not very far at all.”

Florida’s attack on both Black and queer studies and the College Board’s capitulation is certainly reprehensible, but it’s nothing new. This is an old playbook.

During the 1940s and 1950s, educators became one of the primary targets of the second Red Scare, an era characterized by the attacks led by Senator Joseph McCarthy and others on anyone who they wanted to discredit by labeling them communists. And during this time, literally thousands of leftist professors and K-12 educators were dismissed from schools around the country under suspicion of being a communist.

400 teachers in K-12 schools in New York City alone were fired. There was a vicious witch hunt in Florida during this time, and the Red scare was accompanied by the Lavender Scare, which is far less taught and understood. The Lavender Scare was the repression of LGBTQ+ people and their mass firings from government service.

In 1956, Florida officials created the Johns committee, which led a homophobic crusade against queer school teachers that resulted in their interrogations, firings, and even the revocation of their teaching certificates, so that by April of 1963, the committee had revoked the licenses of 71 teachers and had identified another hundred “suspects” in the school district.

Just as the Red Scare and the Lavender Scare were used to purge teachers, the attacks today on what history deniers today have labeled critical race theory and gender ideology are being used to fire educators and exclude any discussion about racism, sexism, transphobia, homophobia, or any form of oppression.

The Washington Post has already identified at least 160 educators who have been fired or pushed out because of their teaching about race or LGBTQ+ issues, and the number is surely far higher than that. This is the dire situation that we’re in today and the real struggle, but I am heartened by courageous educators who are defying these unjust laws.

Geri Schaeffer is a middle school teacher who teaches social studies in Florida, and she signed the Zinn Education Project’s pledge to teach the truth. When she signed the pledge, she said, “I’m willing to die on this. I cannot meet benchmarks for U.S. history or civics if we remove all discussions about racial bias. As the new legislation is worded in Florida, how can I teach the Civil War, emancipation or the 13th, 14th, 15th amendments without discussing racial motivations?”

I would suggest to you all that the rhetorical question posed by Schaeffer has such an obvious answer that it’s ridiculous that she even has to ask it, yet by posing these questions, I think she’s really exposed an acute contradiction of this nation that professes to be the freest nation on earth and yet makes the study of history verboten.

This is a contradiction to the elite’s fear that students will investigate in school, which could lead them to imagining more robust definitions of freedom and to upsetting the current imbalance of power in our society. I just want to highlight some of those imbalances of power or kids in our society.

One in eight children goes hungry in the United States, and 22 percent of Black and Latinx children are food insecure in the richest nation in the world. There are 44 million Americans who have a combined $1.7 trillion in student debt. And of course, Black college graduates disproportionately take on that debt—over $52 thousand compared with white college graduates, who have $28 thousand.

More than 80 percent of students who have been assaulted by police in school since 2011 have been Black. More than 80 percent of LGBTQ+ students who attended in-person school at some point in 2020 and 2021 experienced some form of harassment or assault. This is not freedom, and it’s not the best we can do as a society.

If we’re going to achieve the world that our students deserve to live in, that we all deserve to live in, we are going to have to join a real fight for the access to lessons of the past that they’re trying to hide, and and we’re going to have to envision a much better future, because the truth is Black education has always posed a threat to the American order.

Enslavers outlawed Black literacy and tried to impose the violence of organized forgetting on the enslaved in an attempt to erase their memory of collective resistance. And today’s racists aren’t so bold as to ban the reading of the word like they did for my ancestors. But they do want to ban the “reading of the world,” as Paolo Friere put it, and impose racial illiteracy.

I want to end by saying that we are in a moment in history when we must decide if we will allow a few billionaires and their proxy politicians to return us to the paranoia and oppression of the Red Scare and the Lavender Scare, or if we’re going to fight back, if we’re going to organize demonstrations, walkouts, strikes, and declare that we refuse to go along with a society that has criminalized students’ education and identity. June 10, 2023 has been declared a National Day of Action to Teach Truth. It’s being co-organized by the Zinn Education Project, Black Lives Matter at School, and the African-American Policy Forum. So it’s an opportunity for everybody to get involved in the struggle.

I’ll end with the words of Audre Lorde, the self-described Black lesbian, feminist, socialist, mother warrior poet. She said, “Learning does not happen in some detached way of dealing with a text alone, but from becoming so involved in the process that you can see how it might illuminate your life, and then how you can share that illumination.”

I hope that you all will join us in the struggle to legalize Black history and to take queer studies out of the closet. Thank you.

Kristen Godfrey: Thanks for connecting that to the Lavender Scare. I think as we go into these trans liberation marches and protests that are taking place across the country, we need to make this connection and fight for Black studies when we’re up there talking about getting rid of ant-trans bills.

Next up we have Daniel HoSang.

Daniel HoSang: I want to build on some of the observations Jesse had, especially about linking the attacks on Black studies coming from Florida and other places with a really important theme that Jesse talked about, which is longstanding liberal ambivalence about anti-racist education and the transformative dimensions of Black studies, not the multicultural ones.

What I want to suggest is that the ground on which this project is gaining hold is built on the split that actually comes as much from centrist and liberals as it does from self-identified figures on the right.

The college board itself is deeply fraught. It’s formally a nonprofit, but presides over the administration of thousands and thousands of standardized tests, which have clear race and class impacts. So we’re already on a terrain that it really is not about liberatory education or even critical consciousness. But after 2020, there had been an upsurge and expectations that, if they’re going to have this role credentialing advanced placement courses, as fraught and implicated in tracking that they are, then there should be a course in Black history, in Black studies.

That’s what they’ve been doing for the last two or three years, following processes that had long been established, consulting with primarily college faculty, since the courses are meant to be the equivalent of college courses, including a broad range of concepts.

When that first curriculum was released in early 2022, it was a draft. It’s about 80 pages. It reflected many of those themes in college classes. There was a focus on intersectionality, a clear focus on Black Lives Matter and social movements, and a focus in particular on students making use of the history and contemporary conditions so they might take action, which would be standard fare in any college Black studies classes or ethnic studies classes.

When DeSantis’s Department of Education, then, months, months, months after kind of smelling a campaign opportunity, says there’s no educational value here. Part of what makes that even legible, right?

We’ve consulted with hundreds of college faculty and students who have said, “There’s nothing here that has to do with a profound, deep-seated anti-Black racism that has long regarded Black knowledge production as not to be taken seriously.”

So what comes out of Reconstruction, what comes out of the fight against Jim Crow, what comes out of the fight to desegregate the New Deal is stuck in the past, particular, it has nothing to do with broader questions of liberation, and particularly for non-Black people, the idea is that there’s nothing of interest over there for you. It doesn’t hold with what Du Bois wrote about Reconstruction, that these are the greatest possibilities for multiracial democracy. This is just a course kind of stuck in the past.

The very point that is legible is how after all that work it is producing something with no educational value is rooted in that standing hostility and indifference towards Black intellectual knowledge production.

That said, I don’t think this can be understood as being only about Charlottesville, Richard Spencer, and the far right. We are protecting the superior body of Western European thought as against Black thought. There are clearly millions of people who subscribe to the ideas of the right, but as a project that’s trying to build something like majoritarian support, I don’t think that framework works.

It comes across as too nakedly bigoted and indifferent to individual rights. So I want to suggest, then, that the move that DeSantis and many others made is not just to altogether say we stand against any mention of Black history and the Black presence in U.S. society, but to do what liberals do, which is to split it and say there is a good, acceptable version of this subject and acceptable subjects, and there are bad subjects.

And if you see how the College Board went through, on their own without the demands of the Florida DOE, it does that. So queerness is on the bad list. Black feminism and intersectionality are on the bad list. Social change, disruption, and contestation are on the bad list.

A whole host of other things actually remain on the good list. The striving to overcome individual prejudice, wanting to contribute to national greatness and exceptionalism. They need those narratives. The right needs narratives of Black uplift and accomplishment as a way to legitimate a continued investment in this idea of U.S. exceptionalism, militarism, etc.

That’s partly what’s at stake from my perspective as well: not just the kind of elimination of it but refiguring it as a story of the multicultural United States are these stories possible.

The 1776 Report was a report authored by conservative scholars at the request of and in the waning days of the Trump administration, ostensibly in response to the 1619 report, demonstrates these topics. The 1776 Report has discussions not just of King, but of Rosa Parks and of Frederick Douglass. It’s a multicultural history, and it’s actually not just the kind of argument that Steve Bannon and Steve Miller make about the superiority of the West. It really is very much like what you read in most U.S. history textbooks, which is when there’s a presence of Black people and other people of color, and it’s about both exclusion and incorporation. There’s a kind of natural progression to it.

So that gets us to the third point, which is that all of this builds on how, over the last generation, these bodies of knowledge have been incorporated into U.S. schools and the academies, not as fundamental critiques that might animate broad social movements, but is an effort to simply fill in a chapter here or there.

“Oh, that’s right. We should have included something on Tulsa. We’re going to add chapter 19.5 to the 30 chapters, but every other chapter remains extant. Versus the long insurgent demands of Black studies, queer studies, and ethnic studies that said, we want to lay claim to everything. We imagine reorganizing knowledge production in broad, broad ways.

That’s what C.L.R. James, the radical scholar, writer, and organizer said. Black studies is a study of the West. It’s the study of humanity that can’t be bounded off into these finite chapters. So the fact that DeSantis and others are saying that we are now trading in an illicit, unauthorized form of Black studies that’s unauthorized and builds on that split.

The good version of it was meant to be recognizing the wholesome contributions to the nation, and now these wild-eyed radicals are trying to do something else to it. And I want to say, that’s partly what I think allows it to claim a broader base than if it were just articulated in the language of strict cultural hierarchies. It wouldn’t have the same traction.

There are a broad set of scholars in the field of Black studies who have signed off on what the College Board did. Behind the same logic. We don’t necessarily need critical race theory. We don’t need these other bodies of theory in this course. It’s a so-called foot in the door. It’s important to get these sources out through primary documents.

It’s something we have to struggle with. How did it come to be that a generation after these programs got incorporated, some of their champions have effectively signed off?

Indeed, our field is not meant to be critical of broad ranges of power. We just want an office, a desk, and some courses, so we too can do what you’re doing. Also, that’s not just from DeSantis, that’s coming from within, so we need possibilities to be able to critique that.

In Connecticut where I’m based now, we’ve worked for the last three years on the implementation of a newly required elective class in Black and Latino studies. This class is organized around student demand, and what they wanted was a class on the history of race and racism.

They were very clear. They don’t just want famous firsts. The legislature, and this includes a lot of black and Latino legislators, said, this is not what you’re getting. You’re going to get a multicultural course that’s about representation, about seeing a wider range of historical figures.

And indeed those supporters—they’re all Democrats—said, this is not a course about racism or anti-racism. So I think we have to get our heads around that split about why even the liberals and the center are so quick to reproduce the division between acceptable bodies of knowledge that are about inclusion, representation, affirmation, and ones that are viewed as queer, that are meant to be disruptive, undermining, challenging. That divide has clearly incorporated some people as well.

The very last thing I’ll say is, as Jesse suggested, people are in some ways resisting this everywhere and when you spend time with teachers as Jesse does, you see it all the time.

Students have no interest in these kinds of flat courses. They want the real stuff. They want a place where their own questions can be animated. But I am struck by how the relatively right with a relatively small group has managed to create such havoc over the last three years. They’ve figured out the very sites—textbook approval, board meetings, other sites—where a relatively small amount of resources and attention can cause such traumatic disruptions, panic, anxiety, and the dwindling of solidarity.

Beyond a call to action that gets people to see clearly what’s happening, we also have to figure out where the sites are that we need to summon folks to intervene in and protect, because we’re being dramatically outorganized right now around all this.

Kristen Godfrey: Thank you for providing the language to explain exactly how the liberals are upholding this fascism. Phil, take it away.

Phil Gasper:

I don’t think a day goes by at the moment without a report of another attack on Black studies. A teacher or professor fired, another book banned, new legislation being considered in one state or another.

As the previous speakers have made clear, the attacks are not new, but there’s a new ferocity around these attacks, particularly over the last two years. Our panel is titled “Resisting the Backlash,” and the backlash we’re talking about is specifically the right-wing reaction to the massive Black Lives Matter protests in the summer of 2020.

It’s hard to overestimate the significance of those protests launched in response to the police murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis at the end of May 2020. At the beginning of July, while the protests were still continuing, The New York Times said they may be the biggest protest movement in U.S. history with between 15 million and 26 million participating up to that point. There were hundreds of marches and rallies around the country, some in places where there had never been protests before. Many were in places where there were very few African Americans. Young people, including high school students, played a leading role, particularly young women of color.

And when a police precinct in Minneapolis was burnt down at the beginning of June, polls actually showed that the majority of the U.S. population thought that was justified. Seeing which way the wind was blowing, we had statements from major corporations opposing racism and police violence.

Campus administrations did the same and promised far-reaching structural changes. At the beginning of 2021, the Chronicle of Higher Education declared that this may be a watershed moment in the history of higher education and race.

So anyone who knows U.S. history could predict that at some point the right wing would attempt to push back. And while the Black Lives Matter protests were at their height in the summer of 2020, conservative think tanks like the Heritage Foundation and the Manhattan Institute were already hatching plans, which culminated the following year in the attacks on critical race theory.

According to David Theo Goldberg, the Heritage Foundation promoted the initiative, with Christopher Rufo, a former Heritage fellow who had moved on to the Manhattan Institute, who soon became the main figure spearheading these attacks. It was almost exactly two years ago that Rufo tweeted the following: “The goal is to have the public read something crazy in the newspaper and immediately think, critical race theory. We have decodified the term and will recodify it to annex the entire range of cultural constructions that are unpopular with Americans.” So the goal was not to attack critical race theory in some narrow, specialized academic sense.

You know, as many people said, whoa, well that’s what they teach in law school. We don’t do it on our campus or at our school. But this attack was much, much broader. In Goldberg’s words, the aim was to silence any critical focus on racism today, on structure and institutions, on systems and systemic acts that people deemed racist, and to reshape historical memory regarding race to this end.

Of course, it’s not just an attack on what’s being taught; it’s also an attack on all diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives, which are designed to make education more accessible. Now, on the Left, we often have our own criticisms of some of these programs for being too top-down, too bureaucratic, or too ineffective, but the solution is to expand and strengthen them, not to dismantle them.

The attacks on DEI programs have become so frequent that the Chronicle of Higher Education now devotes a section of its website to tracking them, and all of this is having a chilling effect even where legislation has not yet been passed.

Here’s how a report earlier this month in the Miami Herald describes what’s happening in Florida.

Trainings and events have been preemptively canceled, pending proposed legislation, fearful of becoming the next viral post on anti-DEI social media accounts. Some professors said they are changing the way they teach. Others started recording their own lectures in order to defend themselves, should someone take their comments out of context. Many are considering leaving the state.

These attacks are a response to the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020, but they’re also taking place against the background of the sharp political polarization that has developed in the United States since the financial crisis of 2007-2008, and in the context of the weak economic recovery that followed together with growing economic instability and inequality.

One side of the polarization has been a significant shift to the right by the Republicans. According to an analysis reported by the New York Times in 2019, the Republican Party leans much farther right than most traditional conservative parties in Western Europe and Canada. It is more extreme than France’s National Rally (formerly the National Front).

Since 2008, we’ve also seen the Tea Party, MAGA, and the resurgence of far-right neo-fascist groups and the development of an ecosystem of right wing activists who are able to mobilize their supporters to show up at school board meetings, harass and threaten educators, and amplify whatever is the moral panic of the day on social media and in traditional media.

These groups represent a small minority of the U.S. population, but they have resources, money, organization, and often close ties with the GOP. Many of them receive funding from far-right billionaires.

Of course, their targets are not just Black studies and ethnic studies more generally, as others have pointed out, there’s also an enormous backlash going on against the rights of the queer community and in particular against trans people. Many of these groups also promote conspiracy theories heavily involved in anti-vax campaigns or are climate change deniers. The list goes on.

In times of economic uncertainty, the right always looks for scapegoats. We’re seeing that dynamic play out in today’s attack on Black studies LGBTQ, people, immigrants, and others. The attacks on education are coming from the Republicans and the right. Does that mean that we can look to the Democratic party to defend us? Well, I agree with Daniel. No, we can’t. Even when Democratic politicians don’t support the attacks, they’re slow to respond.

Worse, many of them have supported one central aspect of the backlash to the BLM protests, opposing the cause to defund the police and ramping up tough-on-crime rhetoric. Earlier this month the Washington Post reported on a growing movement within the Democratic Party pushing a more aggressive line on crime and publicly breaking with some of the reform policies that spread widely across the country after the killing of George Floyd by police in Minneapolis.

And for those of you watching what’s going on in Atlanta at the moment with the brutal repression of the Stop Cop City protests, it’s worth remembering that this is happening in a city that is run by the Democrats.

There’s a deeper reason, I think, why the Democratic Party is part of the problem, not part of the solution. At the end of the day, whatever the rhetoric it uses and whatever the promises it makes, its primary commitment is to defending capital. That’s why Biden and a Democratic Congress prevented railroad workers from striking last year and imposed a settlement on them that they had already voted down. It’s why the Biden administration has given the green light to the Willow Project for more oil and gas drilling in the Arctic, which will make the climate crisis even worse.

We’ve seen this dynamic play out many times before. Democrats are elected by making big promises to their working class supporters, but when the system goes into crisis, the promises are broken and they bail out Wall Street and the big corporations. This then opens the door for right-wing populists who take advantage of the disillusionment.

Of course, the right-wing is even worse, but this is the merry-go-round of U.S. politics with the center shifting farther and farther to the right as the years go by.

Despite what’s happening in mainstream politics, there’s also been a revival of the Left in the U.S.: the Occupy movement in 2011, the support for Bernie Sanders’ two presidential campaigns, the rise of Black Lives Matter. And today we’re also seeing a small but important revival of the labor movement.

I’m going to end on this point. One of the most significant areas where this is taking place is in education. Over the past several years, we’ve seen significant organizing and strikes by both public school teachers and in higher education. In the public schools, this goes back to the Chicago Teachers Strike in 2012 and the multi-state teachers rebellion in 2018. This past week, school staff walked out in Los Angeles and were supported by the teachers’ union, UTLA. And the unions have now declared a major victory after three days on strike.

In higher education, there has been a continuing wave of successful unionization drives by graduate students. There have recently been lopsided pro-union votes at Boston University, Yale, Northwestern, Johns Hopkins, the University of Southern California and the University of Chicago, with an average of 94 percent voting yes in these elections. Even undergraduate workers are organizing on some campuses.

There have also been successful, or at least partially successful, graduate student strikes, some lasting for many weeks at Harvard, Columbia, NYU, the University of California system, and most recently at Temple University.

And, as people have mentioned at Rutgers, there’s been amazing organizing taking place. I think the most significant thing about the Rutgers organizing is that it crosses the traditional divisions and hierarchies of higher education. This isn’t just organizing by one group, by graduate students or faculty, or by adjunct faculty. This is by all of them, full-time and adjunct faculty, graduate workers and post-doctoral associates. We don’t know if the strike’s going to happen, but it could very soon, and the fact that they’ve organized in this way is particularly inspiring.

I raise these examples, even though in most of them, the focus has been on economic issues, and most of them have not taken place in the states that are at the center of the attack on Black studies.

I think they’re still relevant for two reasons. First, as the teachers’ strikes and uprising in 2018 showed, strikes can spread from one state to another, and they can take place in so-called red states just as much as in blue states. And second, I think one of the key roles of socialists is to connect issues and to point to common interests.

Our argument is that the fight for economic justice must also be a fight for racial justice, for trans justice, and so on. The issues intersect. So our organizing has to intersect. As the old Wobbly slogan puts it, “An injury to one is an injury to all.” I’m excited by the revival of labor activism because it gives us an arena where we can make these arguments and it gives us a way to start rebuilding the militancy that we saw in 2020.

And that’s what we have to do, I think, in order to defeat the right-wing backlash.

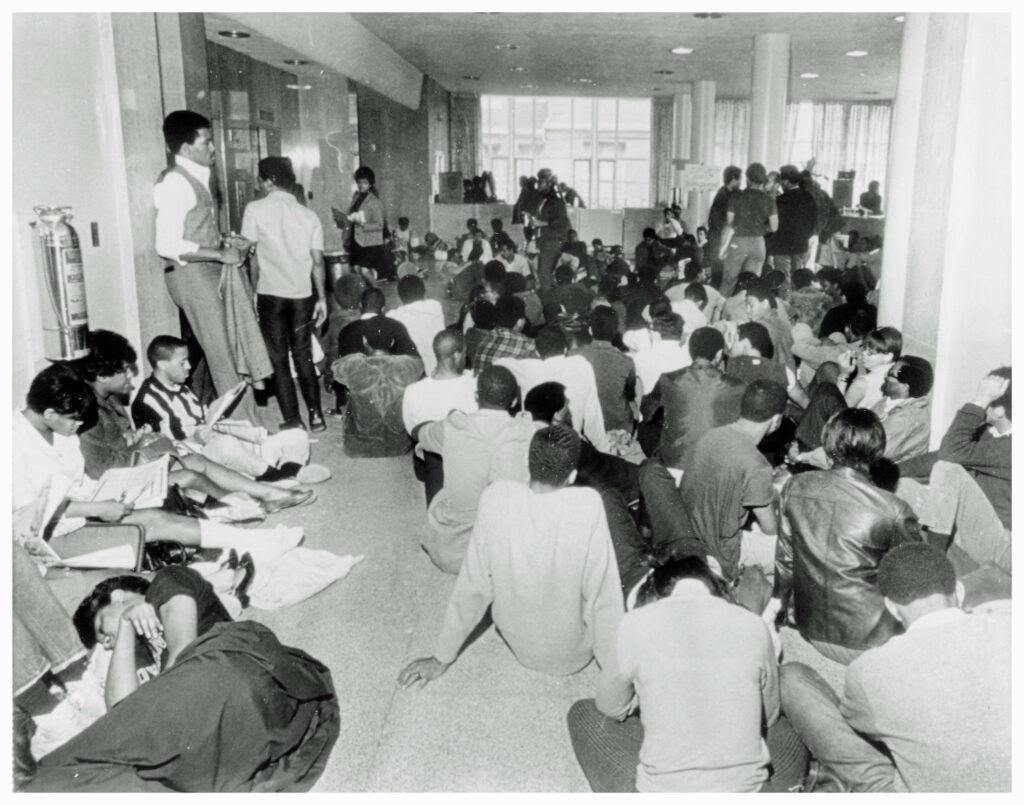

Featured Image credit: Wikimedia Commons; modified by Tempest.

We want to hear what you think. Contact us at editors@tempestmag.org. And if you've enjoyed what you've read, please consider donating to support our work:

DonateKristen Godfrey, Jesse Hagopian, Daniel HoSang, and Phil Gasper View All

Kristen Godfrey is a member of the Tempest Collective.

Jesse Hagopian is an ethnic studies teacher at Garfield High School in Seattle, a member of Black Lives Matter at School and its the National Steering Committee, and co-editor of Black Lives Matter at School. He also organizes with the Zinn Education Project.

Daniel HoSang Daniel teaches ethnicity, race and migration in American Studies at Yale University, and is the author of a Wider Type of Freedom: How Struggles for Racial Justice Liberate Everyone.

Phil Gasper is a socialist and anti-racist activist who has worked in higher education for over forty years. He is currently a faculty member and a member of AFT Local 243 at Madison College in Wisconsin. Phil is co-editor of the independent socialist journal New Politics and a member of the Tempest Collective.