Hal Draper’s America as Overlord

A foreword

By the time I first met Hal Draper in 1963 when I was a new graduate student in the sociology department at UC Berkeley, Hal had been an acquisitions librarian on campus for some time. He studied for this new profession when he was in his forties after moving from New York where he had been for several years the editor of the weekly Labor Action, an organ of the Independent Socialist League (ISL).

The ISL was then the current embodiment of a political tendency that traced its origin to a political break with Leon Trotsky: Trotsky characterized of the USSR as a degenerated workers’ state that had to be defended against Western imperialism, while at the same time, he argued, a political revolution was necessary to overthrow the Stalinist bureaucracy. The Trotskyist dissidents argued that the USSR had become a new form of class society that they called “bureaucratic collectivism,” which had to be overthrown by a revolution that would be not only political but also social, precisely because a new class would have taken power. Moreover, the ISL held that the USSR was not defensible, as Trotsky believed, particularly after it had invaded Finland and allied with Nazi Germany to eliminate Poland as an independent nation in 1939. These foreign invasions in fact originally set in motion the evolving dynamic of the split with Trotsky. Internationally, both the Communist parties that had become entirely subservient to Moscow’s interests and the liberal and conservative defenders of capitalism had to be confronted by a revolutionary Third Camp tendency under the slogan “Neither Washington nor Moscow.”

I quickly became one of several radical socialist students for whom Hal Draper served as a mentor. For me, Hal became the embodiment of what a Marxist scholar should be. I consulted him on numerous occasions on questions pertaining to the ideas and politics of Karl Marx as well as on the political issues of the day, whether these concerned the labor movement or our position on free speech. One result of this latter consultation was Hal Draper’s decision to write a seminal article outlining the grounds for his defense of free speech.1

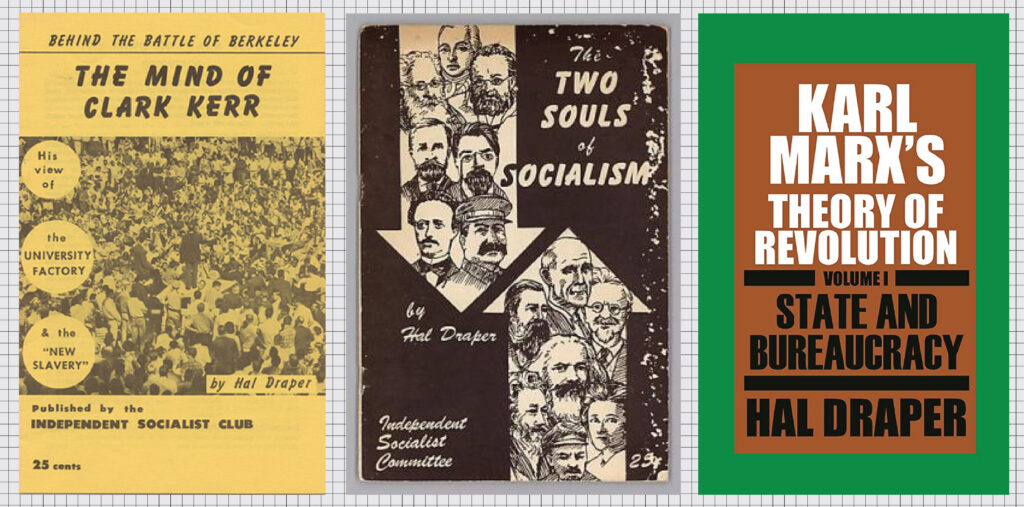

As an authentic Marxist, Hal Draper was a political practitioner of the first order, even though I don’t recall he ever used the term “praxis,” a fashionable term in academic Marxist circles. This became evident in the fall of 1964, exactly a year after I had met him, when the Free Speech Movement (FSM) broke out on the Berkeley campus. Hal, working closely together with the newly founded Independent Socialist Club (ISC) (of which he was the main political leader, and I was a member), played a major role in that movement. Besides being a frequent speaker at the FSM rallies, the fifty-year-old Hal Draper played a crucial ideological and political role through his widely disseminated pamphlet The Mind of Clark Kerr, an incisive and detailed study of the ideas of the industrial relations professor who had become the president of the University of California. Draper revealed and critically analyzed Kerr’s vision of universities becoming a central part of the “knowledge industry,” an analysis that was immediately echoed by Mario Savio, the FSM leader, in his famous speech on December 2, 1964, denouncing Kerr’s idea of the university as if it were a factory. To combat the university as the factory that Kerr envisaged, Savio exhorted the Berkeley students “to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels. . . upon the levers, upon all the apparatus, and you’ve got to make it stop.”2

During that struggle, I also discovered Draper’s impressive tactical talents. At the height of the FSM struggle, elections were scheduled for student government, a typical undemocratic “sandbox” institution with close ties to the world of fraternities and sororities from which practically all radical and liberal students stayed away. (Graduate students were excluded from membership for fear of their radicalism.) Draper however, convincingly argued to the skeptical ISC members, myself included, that this time the relation of forces among the students had radically shifted and that the FSM militants and sympathizers should participate in the elections and attempt to take over student government. Indeed, this is what happened, with a decisive vote removing the student government leaders who had opposed the FSM from the beginning.

In the age of postmodernism and assorted non-rational and irrational tendencies, Hal Draper stands as an excellent representative of the left wing of the Enlightenment, in the tradition of Karl Marx, who pursued a rational and revolutionary theory and method of understanding and changing society. Always willing to take an unpopular stand when the political situation required it, Draper cut through the soft-headedness common in the American left while at the same time welcoming, encouraging, and praising new radicalizing forces, no matter how politically raw these might have been. Thus, quite in contrast with several of his former ISL comrades such as Irving Howe, the editor of Dissent, who were busy castigating and excommunicating the New Leftists, Draper welcomed and defended them in a comradely but critical fashion.3 Members of the ISC such as myself made copies and widely distributed Draper’s article “In Defense of the ‘New Radicals’” among fellow young Berkeley radicals.

Without a doubt, Hal Draper’s crowning intellectual and political achievement was his multi-volume treatise Karl Marx’s Theory of Revolution published by Monthly Review Press in the seventies and eighties, after he withdrew from organized active political activity. In a highly erudite but very accessible study of the ideas and actions of Karl Marx, Draper more than convincingly demonstrated that Marx’s views on socialist revolution and democracy were inextricably intertwined, thus creating the fundamental basis of what Draper had earlier called “socialism from below.”

Political Background to America as Overlord

The nine articles in this collection were all published between 1954 and 1969. Although these articles were read by people in many parts of the world, left-wing people in the United States were the primary audience that Hal Draper thought needed to be persuaded by his arguments and evidence. At the same time, these readings were amply utilized to educate ISL and, later, ISC members as well as many members of the IS (International Socialism, the organization that succeeded ISC).

Within this period, we need to single out the series of dramatic events that took place in 1956, some of which had a substantial impact on the American left. These events included the twentieth party congress of the Communist Party of the USSR in February, at which Khrushchev exposed many of the crimes committed by Stalin; the Hungarian Revolution in October and November; and the British, French, and Israeli invasion of Egypt in retaliation for Nasser’s nationalization of the Suez Canal at the end of October. The twentieth party congress and the Hungarian Revolution in particular had a great impact on the American Communist Party, at the time the U.S. left’s largest and in many ways dominant organization. After losing in the early fifties a very large number of members, many of whom had been the direct victims of Senator McCarthy’s witch-hunts, the CP also saw thousands of members who had withstood McCarthyism and remained loyal leave the organization in 1956 and shortly afterwards. The American Communist Party, which had now become little more than a rump, lost much of its hegemonic ideological and political role within the U.S. left, a hegemony that had been gained mostly during the years of the Popular Front that began in the mid-thirties and during the Soviet alliance with the U.S. and its allies during World War II.

While the former American Communists were generally repelled by the crimes of Stalin and the bureaucratic ossification of the regime over which he and his successors presided, this welcome reaction was not for the most part accompanied by a deeper structural understanding of the nature of the Soviet system and particularly of the great perils posed by the lack of democracy in a one-party state controlling the lion’s share of political, economic, social, and cultural life. This helps to explain, for example, the sympathy that many of these former Communists expressed for Fidel Castro and Che Guevara, favorably contrasting their romantic, revolutionary, and apparently free-wheeling élan with the stodgy and conservative bureaucratic behavior of Cuba’s Soviet partners. Unfortunately, most of the former American Communists were reluctant to look “under the hood” of this new Cuban vehicle, where they would surely have found an almost complete copy of the organizational and structural features of the Soviet state they had so much come to dislike. That is the main reason why they failed to distinguish the higher political popular participation in Cuban Communism from the quite different notion of democratic control, which was as absent in Cuba as in the USSR and the rest of the Soviet bloc. This attitude was particularly tragic in light of the fact that many of these former Communists and their children (several of whom I personally liked and politically worked with at Berkeley) played valuable roles as activists in the civil rights, student, and antiwar movements. Many of them were also to play an important role in the New Left and its principal organization, Students for a Democratic Society (SDS).

The other audience that Draper had to address was American liberalism and the small remnants of right-wing social democracy. Under Draper’s editorship, Labor Action, together with its sister theoretical journal, The New International, had for years zeroed in on criticizing Americans for Democratic Action (ADA), the principal organization of American liberalism for its support for American cold war policies and accommodations to McCarthyism. The much less important but still significant right-wing social democracy also came under attack as in the notorious case of Sidney Hook, a former revolutionary Marxist who had turned apologist for McCarthyism, with his slogan of “Heresy Yes, Conspiracy No” and his conclusion that as a conspiracy American Communism had no right to exist and should not be tolerated.

In 1960, the organization SDS was founded under the sponsorship of the League for Industrial Democracy (LID), a right-wing social democratic organization, and the United Auto Workers (UAW), at the time perhaps the most politically liberal American union. It did not take long before the obsessive anti-Communism of the UAW, and especially of the LID, would clash with the far less obsessive but soft-headed attitude toward the Soviet bloc prevailing in the brand new SDS as well as in most of the American left. These latter political currents tended to consider, for example, that any strong critique of, let alone opposition to, the Soviet bloc was politically suspect and came close to an apology for U.S. imperialism. At the same time, the liberal and right-wing social democratic anti-Communism was based in their open and even militant cold war support for the United States in the conflict with the Soviet bloc. However, there was an alternative perspective that did not really require a high degree of political and theoretical sophistication and should have been obvious to independent, radical democratic minds: to oppose both imperialisms, the Communist one led by Moscow and the capitalist one led by Washington, while supporting the self-determination of nations, be that nation Hungary in 1956 or Cuba in the early sixties. Unfortunately, this point of view was only held by a small minority of SDS members.

Once the SDS rejected and broke with the obsessive anti-Communism of their original liberal and right-wing social democratic sponsors, it remained for a few years a fairly open political organization that attracted an increasing number of radicalizing young people to its ranks. But under the impact of the growing and long-lasting U.S. imperialist attacks on Vietnam and Mao’s Cultural Revolution in China that began in 1966, the SDS took a turn toward an increasingly pro-Stalinist politics. However, this time, that kind of politics did not take the form of sympathies with the USSR, a country that continued to be perceived as conservative and even headed toward the restoration of capitalism, but with Mao’s China and its supposedly anti-bureaucratic politics, especially after the Cultural Revolution. However, it did not take long before the Maoist hegemony in SDS turned into Maoist political fragmentation and fratricide with the consequent disappearance of SDS by the beginning of the seventies.

The articles in the America as Overlord collection

Four of the articles in this collection are exclusively concerned with Ameri- can and Western imperialism. Three of these deal with the U.S. imperial possessions in Okinawa, Samoa, and Guam. The fourth one is about the important Suez Canal crisis of 1956 when the Israeli, French, and British armed forces invaded Egypt, then under Nasser’s nationalist leadership, because he dared to nationalize the Suez Canal. Besides repudiating the invasion of Egypt, Draper relates and analyzes why and how, in this instance, the U.S. chose to act as the imperial arbiter, successfully pressuring the invading countries to withdraw their troops.

Three other articles also deal primarily with U.S. imperialism, but also take into account and analyze the role that the local Communist parties and the USSR played in these three situations. First, there is an article on Guatemala dealing with the CIA-organized invasion that overthrew the democratically elected government of Jacobo Arbenz in 1954, and the role of the local Communist party in that country. Second, there is also an article discussing Vietnamese revolts in the fifties and sixties organized and led by forces independent of North Vietnamese Communism, and their political potential as a democratic alternative for the Vietnamese people. Third, there is an article on John F. Kennedy’s disastrous imperialist policies toward the Cuban revolutionary government led by Fidel Castro that came to a critical head during the CIA-organized invasion that was defeated by the Cubans in April of 1961. A recurring theme that unites these three different situations was Hal Draper’s insistence that principled and militant opposition to U.S. imperialism should be accompanied by the development of a left-wing independent political posture on the part of revolutionary socialists. This was necessary in the imperial countries—to fight against any surrender of the right to national self-determination of the countries resisting imperialism that both metropolitan liberals and conservatives were likely to advocate. At the same time, in the colonial and subject countries, this kind of independent political stand was necessary so they would be able, when the occasion required it, to successfully prevail in any conflict with any victorious Communist movement that we knew, based on ample experience, would proceed to establish a one-party state suppressing independent unions and every other expression of democratic life, particularly those developing from below, let alone imprisoning those who opposed their new rule.

Behind Yalta

Particular attention should be paid to the first and last articles in this collection, which are also the two longest, that are truly exceptional in quality and played a major role in my own political education. The first article, well over fifty pages long, is titled “Behind Yalta: The Truth About the Second World War.” This is an indispensable article for those who want to understand why World War II was fought and the origins of the cold war that lasted from the late forties until the collapse of the Soviet bloc in the late eighties and early nineties. Draper’s account of the meeting that Stalin, Churchill, and Franklin D. Roosevelt held at Yalta in February of 1945, toward the end of World War II, and an earlier meeting of Churchill and Stalin in Moscow in October of 1944 show the cynical, Realpolitik content of those encounters in which by far the dominant topic on the agenda was how to divide the world among the victorious imperialist powers that would emerge with the defeat of fascism. When I read those descriptions, I could not help but draw a parallel with the legendary Mafia meetings to adjudicate jurisdictional disputes concerning the production and marketing of various illegal drugs and illegal union, loan sharking, and gambling rackets.

Draper’s well-documented article and very rich historical account gives the lie, on one hand to the often-repeated Western ideological proclamation pretending that the Western powers fought World War II and the cold war against the Soviet bloc to defend freedom and democracy. On the other hand, it also gives the lie to Moscow’s pretense to be a defender of Communism when it is clear that it assured the Western powers that it would not support any Communist takeover in Western Europe provided that the USSR be given a free hand in Eastern Europe. In particular, this was why Stalin withheld aid to the local Communists in the Greek Civil War in exchange for his getting the green light to take over Poland. Of course, those agreements at the end of World War II lasted no longer than the relation of forces among the contending powers that gave birth to them, a relatively unstable situation that gave birth to the almost forty-five years of the cold war.

These sorts of deals had nothing to do with FDR and the Democratic Party establishment being soft on Communism or any of the other slanderous legends spread by the American right about the cold war. Rather they were the outcome of a cynically well-calculated imperialist exchange. One reason why the Ameri- can right wing had a certain degree of success in spreading such falsehoods was that most Americans simply did not know that at Yalta FDR was not only supposed to contain Stalin but also Churchill, who was trying to retain as much as he could of the British Empire, an intention opposed to the American imperialist perspective of opening the whole world to its interests and hegemony. In a few years, Churchill’s designs were brought to naught by Indian independence and the anticolonial revolution, let alone Great Britain’s clear subordination to American economic and political power. Once Britain had lost much of its power and became the closest ally of the United States by the 1950s, especially after Britain was put in its proper place by Eisenhower during the Suez Crisis of 1956, Americans could not understand why FDR had to play Stalin against Churchill. Again, it was Realpolitik and not any softness toward Communism that guided FDR’s behavior at Yalta in 1945.

National liberation

The last article in the collection, titled The ABCs of National Liberation, was perhaps of even greater importance in the political education of the members of the Berkeley ISC including myself. Although written as a pedagogical primer for young socialist students, it was not less brilliant and original in its analyses. As a political group that under the leadership of Hal Draper, the ISC was of course for the immediate withdrawal of U.S. troops from Vietnam (as well as everywhere else for that matter). The issue also arose—as will almost inevitably arise in struggles for national liberation—of what attitude Ameri- can revolutionary socialists should adopt toward the specific political groups that are leading the struggle in the countries subject to U.S. domination. This was a particularly vexing problem in the case of Vietnam in light of the great political power and influence exerted by Communist North Vietnam and the National Liberation Front (NLF), its South Vietnamese branch and ally, keeping in mind once again that as soon as they took power they would establish a top-down and thoroughly undemocratic one-party state (as indeed happened after the victory over the United States), thereby preventing the independent organization of workers and other oppressed groups.

That is why Hal Draper had shown a great deal of interest in the Buddhist-led revolts that occurred in Vietnam in the fifties and sixties in articles that are included in this collection. This political development in Vietnam should not be surprising since, as has happened in numerous cases elsewhere, authentic mass rebellions have often been organized by leaders whose ideologies have been framed in religious terms. However, the Vietnamese Tet offensive in 1968 demonstrated to Draper that the NLF had the overwhelming support (or at least acquiescence) of the great majority of the Vietnamese people, and that the Communist-led NLF was the only organized alternative left to defeat U.S. imperialism. In response to the new situation, Hal Draper came out in this document not only for the immediate withdrawal of U.S. troops (that was, of course, never in question) but also for a perspective favoring the military victory of the NLF while remaining opposed to its politics.

What I found especially valuable about this article was that Draper also presented a whole methodology to guide the ISC, and more broadly the left, on what stand to take regarding a variety of political situations involving not only national liberation movements but also international conflicts such as wars. Following the strategist Carl Von Clausewitz and the Marxist tradition, Draper defined this as the continuation of politics by other means. Draper’s analyses in this article addressed such widely different cases as Ethiopia’s resistance to Italian imperialism and the Spanish Civil War in the 1930s, the clash between China and Japan during World War II, the conflict between Stalin and Tito’s Yugoslavia in the late forties and early fifties, the Algerian struggle for independence in the fifties and sixties, and the U.S.-sponsored invasion of Cuba in 1961. Draper’s approach is today very useful in understanding and reaching political conclusions based on a democratic and revolutionary socialist perspective regarding such diverse places and conflicts as Syria, Hong Kong, Iran, and especially Ukraine. These situations have become an important source of conflict with the widespread left political phenomenon of “campism,” meaning the uncritical political support that many on the left give to any country or movement that opposes U.S. imperialism no matter how reactionary and antidemocratic that regime or movement might be.

Categories

We want to hear what you think. Contact us at editors@tempestmag.org. And if you've enjoyed what you've read, please consider donating to support our work:

DonateSamuel Farber View All

Samuel Farber was born and raised in Cuba and has written numerous articles and books about that country as well as on the Russian Revolution and American politics. He is a retired professor from CUNY (City University of New York) and resides in that city.