Giving credit to the wrong class

“Explaining” strikes for union recognition

In his response to my critique in Tempest of his argument about the role of NIRA Section 7(a) as “spurring” the upsurge in strikes in 1933, Eric Blanc writes, “Kim Moody’s new long polemic…can’t explain why workers struggles began to focus on union recognition after the gov passed 7(a) recognizing the right to organize.” While my “long polemic” did note the large number of recognition strikes in 1933–1934, it didn’t explain their rise separately because they have historically followed the trend of strikes in general and been a regular feature of worker upsurges for decades, as I will show below. To put it simply, recognition strikes were nothing new in the immediate post-7(a) period. My basic argument about the upsurge of 1933, shown in Table I of my Tempest article, was that the strike wave of that year actually began to take shape before 7(a) was passed in June and that it was encouraged by an upswing in the economy in early 1933, the prior accumulation of organizing experience and radical rank and file leadership (the militant minority) of the previous three years, and to a lesser extent, once 7(a) was passed, by the brief though unmeasurable psychological effect of Section 7(a) on the attitudes of workers and union leaders.

The authors of the Brookings study of National Recovery Administration (NRA) labor boards, for example, reported the following rise in strike activity in early 1933, which they seemed to think was significant:

In January 1933 the number of man-days lost in disputes rose rapidly to a total of 240,912 an increase of some 500 per cent over December. In February there was a recession but in March the figure advanced sharply again to 445,771. This advance may have been due to the spurt in production and prices which began shortly after the bank holiday. The number and severity of industrial disputes continued to increase in April (535,039 man-days lost) and May (603,723 man-days lost).1

After that it fell slightly in June and then rose rapidly in July with the ink on 7(a) hardly dry. This study also attributed the July upsurge in large part to the “business boomlet” of that time.2

Furthermore, there was a strong continuity between pre- and post-7(a) strikes. As Michael Goldfield writes about pre-7(a) organizing, “[B]efore FDR signed the NIRA on June 16, 1933, organization was virtually complete in many areas in both the garment and coal industries.”3Garment workers and miners alone accounted for 55 percent of all strikes in 1933. Recognition was a major issue in both industries, so pre-7(a) organizing by these groups was responsible for a significant proportion of recognition strikes.4 The July strikes and strikers were also concentrated in garment (including hosiery) and mining. In other words, the jump in strikes in July was to a significant degree a continuation of the pre-7(a) organizing drives and strikes in garment and coal mining already underway in early 1933.

Later in 1933 auto workers would continue the unbroken line of mass strikes in what Nelson Lichtenstein described as “the Depression-era auto insurgency” that began in January at Briggs and in February at Murray Body and Hudson, followed by further strikes at White Motors, Willys-Overland (Jeep), and Chevrolet, all before 7(a) in early 1933.5 In short, there was a great deal of continuity in strikes, almost certainly including those for recognition, before and after 7(a) became law.

Unfortunately, the Bureau of Labor Statistics stats do not include the reason for striking in the monthly figures, so I can’t “prove” that all of those early 1933 strikes were specifically for recognition, though “organizing” drives are by definition about union recognition and in those days usually required strikes. The general flow of recognition strikes as part of the overall pattern of strikes since at least the turn of the twentieth century also indicates that recognition strikes rose and fell along with the general level of strikes.

Recognition strikes were not new in 1933

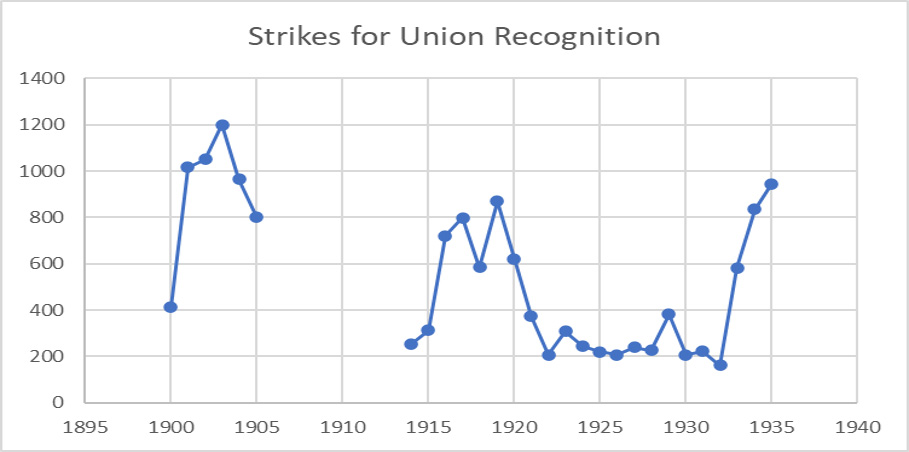

One reason the “focus on union recognition” cannot be explained in the way Blanc would like is that this focus was not new or unique to the upsurge of 1933. Union recognition had by then been a regular goal of strikes and a feature of strike waves for three decades or more. Blanc’s graph showing the rise in the number of workers striking for union recognition begins in 1922. Had he extended it to the beginning of the century to give us a more complete picture of union recognition strikes, it would have shown that they were a regular feature of class conflict and that increases in strikes for recognition were typical of the two major strike waves of that period: 1901–1905 and 1916–1919. The graph below shows the course of strikes for union recognition from 1900–1935, the last year of the NRA. Statistics for recognition strikes are not available from 1906–1913, hence the break.

During the first great twentieth century upsurge of strikes and union organization in 1901–1905, the number of recognition strikes followed the upward trend in strikes and rose from 414 in 1900 to 1,200 by 1903, more in 1903 than in any year during the life of the NRA and 7(a). Altogether, there were more strikes for union recognition at its height in 1901–1903 (2,577) than during the lifespan of the NRA in 1933–1935 (2,363).6 In 1901–03 there was no legislation remotely favorable to unions or even a liberal administration in Washington to get the credit for “spurring” such action. Due to employer opposition, workers had to strike to win recognition in order to bargain over the underlying issues. Florence Peterson wrote of the 1901–05 strike wave in her 1938 Department of Labor study of strikes since 1880 (noting their increased importance): “Strikes increased with the return of industrial prosperity and the expansion of labor organizations in 1899 and the first years of the twentieth century. Many of these, as was to be expected after a long period of wage reductions, were for wage increases, although union recognition became an increasingly important issue. About as many workers were involved in union recognition strikes between 1901 and 1905 as were involved in wage disputes.”7

In response to this insurgency the metal trades employers launched the “Open Shop” crusade in manufacturing as early as 1903 to counter the trend toward collective bargaining, and the number of strikes, including those for recognition, fell, as the graph shows.8

The massive 1916–1919 strike wave also saw an increase in strikes for union recognition. Altogether, there were 2,973 strikes in this period that included union recognition as a major goal. During the brief eight-month life of the National War Labor Board in 1918, with its 7(a)-style language, the number of union recognition strikes actually dropped from 799 to 584 as the government encouraged “peaceful” collective bargaining with American Federation of Labor (AFL) unions and discouraged strikes for the sake of war production—all a preview and an example for those who designed the NRA and 7(a). The strike wave continued after the war with the return to normal “private enterprise” and without 7(a)-style “permission” in 1919. Union recognition strikes reached a high of 869 in that year, more than in either 1933 or 1934, before falling with the economic slump of 1920 and the state repression that accompanied it.9

Furthermore, as Blanc’s graph for the number of strikers and mine for the number of strikes indicate, even with the low level of strikes after 1922 those for union recognition remained a fairly steady proportion of all strikes. Then with the upswing in industrial production beginning in 1925, such strikes began to increase significantly from 206 in 1926 to 382 in 1929, rising to 36 percent of all strikes, a higher proportion than in 1933. Their growth was halted only as the Great Depression took hold in 1930, and their number fell for the next three years.10 Had the economy not slumped that year, it is likely the trend toward union recognition strikes and collective bargaining would have continued and grown well before 7(a) or even the 1932 Norris-LaGuardia Act, which contained the same language. By 1933, 7(a)-style language was already old news. Union recognition was well established in a number of industries and trades, some since the 1890s, despite employer opposition, and the right to strike for recognition long official AFL policy. So, what also explains the “focus on union recognition” in 1933 is that this was already a well-established goal of workers in seeking collective bargaining and the actions they took to win it, which increased when the conditions for striking improved, as they did in 1901, 1916, and early 1933.

Dynamics of recognition strikes under NRA

The overall dynamics of worker activity under the NRA imply a causation to the direction in strike activity that is the opposite of Blanc’s assertion that “[t]he evidence is overwhelming, however, that Section 7(a) played a major role in boosting and shaping the era’s labor insurgencies” (emphasis added). Aside from the obvious fact that 7(a) did not shape the major gain for worker organization of the era, industrial unionism, neither did it shape the direction of strikes even for union recognition. Quite the opposite. The number and proportion of strikes for union recognition rose from 1933 to 1934 precisely as the “psychological effect” of 7(a) faded, even according to the Brookings study; the relatively small number of workers participating in labor board elections dropped by over half under the newly created (but pre-1935) National Labor Relations Board;11and the disillusionment with 7(a) spread, with workers calling the NRA the “National Run Around” and its official symbol, the Blue Eagle, the “Blue Buzzard.”

The major Brookings study of the NRA described the experience and attitudes that drove the workers’ loss of “their earlier faith in the NRA” by early 1934, when, the authors wrote, “There was a growing resentment in labor ranks against continued unemployment, inadequate weekly earnings, increasing discrimination on the part of employers against union workers, and the growth of company unions.”12 These were the actual experiences of the first few months of 7(a) and the NRA. Striking for union recognition or anything else was a necessity imposed by persistent employer opposition and the Roosevelt administration’s and the NRA’s priority of promoting business stability and recovery (profitability) as the means to economic growth.

So, in contrast to Blanc, I interpreted the increase of strikes specifically for union recognition—which, as I showed, far outstripped the use of NRA labor board representation elections—as a sign of workers’ distrust of or frustration with the NRA and the institutions set up under it to implement 7(a). Section 7(a), after all, was merely a set of words to be implemented under the NRA codes, and its psychological impact was relatively brief.13The implementation of 7(a) came primarily through the NRA’s code administration and labor boards. Almost without exception, the codes administered by the NRA were completely dominated by employers. I gave the examples of the NRA’s pro-employer impact of the codes on unions in auto, textiles, and shipbuilding. In addition, a significant number of those who struck in the first six months after NRA was passed in 1933 did so against the codes in their industry: 95,000 garment workers, 55,000 silk workers, 70,000 coal miners.14In these cases, the NRA implementation of 7(a) inspired strikes, but not in the way Blanc attributes it.

The labor boards were hardly any better. For one thing, employers routinely ignored and disobeyed board decisions in favor of bargaining and the law, generally with no consequences. For another, as the Brookings’ study of the NRA’s labor boards argued, 7(a) “did not require recognition of existing trade unions…as exclusive agencies for collective bargaining…[,] outlaw company unions,” or “compel employers to come to terms with employee representatives.” “The Board’s main efforts were,” the authors concluded, “to settle strikes,” not to encourage them.15In fact, faced with increasing strikes in July, the National Labor Board was first set up in August 1933 to “allay this unrest and to bring about a state of industrial relations favorable to the success of the re-employment

campaign.”16 So, when the economic conditions improved, as they did in 1934, workers struck for recognition rather than use the NRA national or regional labor boards. Furthermore, as the Brookings study of the NRA as a whole concluded, “The NRA thus threw its weight against labor in the balance of bargaining power between capital and labor.”17This, too, provided a strong motivation to strike.

Just as it had been in the past, it was necessary to strike during the life of the NRA and 7(a) more often than not to win recognition and collective bargaining. That, along with the underlying issues, favorable economic conditions, development of grassroots leadership, and long-time practice of striking for recognition, explains why these strikes in particular continued to increase while the use of NRA boards declined after the initial psychological effect wore off. Under the NRA, striking was still typically the only way to force real negotiations for a contract on recalcitrant employers, as opposed to “talks” or mediation with no conclusion, because the NRA boards did not have the power to force employers to reach an agreement with a union. Arbitration was voluntary and almost always came as a result of a strike.

The driving conditions of work behind the general upsurge in 1933—wages, hours, and, above all, speed-up—were the major “spur” to action for industrial workers. Fighting for union recognition was the means to force bargaining and win binding agreements over these issues. The ups and downs of the economy enabled or discouraged direct action. The fight for union recognition and collective bargaining, like industrial unionism, was the creation of organized workers themselves long before 7(a) and the NRA. To attribute this aspect of collective worker creativity and agency to a piece of vaguely worded legislation and its largely pro-employer institutions is to give credit to the wrong class.

Featured Image credit: Artwork by Nevena Pilipovic-Wengler.

We want to hear what you think. Contact us at editors@tempestmag.org. And if you've enjoyed what you've read, please consider donating to support our work:

DonateKim Moody View All

Kim Moody was a founder of Labor Notes and the author of several books on US labor. He is currently a Visiting Scholar at the Centre for the Study of the Production of the Built Environment of the University of Westminster in London, and a member of the National Union of Journalists. He is the author of many books, including On New Terrain: How Capital is Reshaping the Battleground of Class War, In Solidarity: Essays on Working-Class Organization and Strategy in the United States, and Tramps & Trade Union Travelers: Internal Migration and Organized Labor in Gilded Age America, 1870-1900.