The making of a Black Bolshevik

A review of Winston James’s new biography of Claude McKay

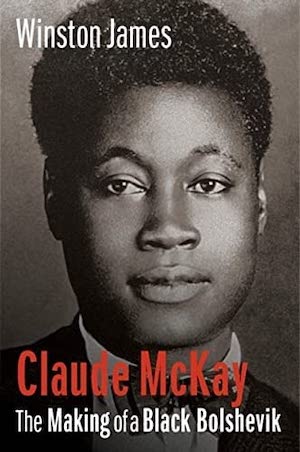

Claude McKay

The Making of a Black Bolshevik

by Winston James

Columbia University Press, 2022

The revolutionary Jamaican poet Claude McKay deserves a good Marxist biographer and has found one. Winston James’s new book on McKay illuminates the mind and art of one of the most important writers of the early twentieth century as it responded to the seismic contest between capitalism, colonialism, and Socialism in the age of the Russian Revolution.

Known to many for his earth-shattering poem “If We Must Die,” which documents the racist pogroms against Blacks in 1919, McKay comes off the pages of this book as a profoundly sensitive artist and political thinker whose sympathies for the poor, the marginalized, and the dispossessed convinced him that socialism was “the greatest and most scientific idea afloat in the world to-day.”

Twenty-three years ago, McKay featured as one in a gallery of Caribbean radicals and intellectuals in James’s excellent Holding Aloft the Banner of Ethiopia: Caribbean Radicalism in Early 20th-Century America. One year later, James published a slighter book, A Fierce Hatred of Injustice: Claude McKay’s Jamaica and His Poetry of Rebellion. The Making of a Black Bolshevik is the first volume of his planned two-part biography of McKay. This first volume takes him from his birth in Jamaica in 1889 to the year 1921.

James’s overarching thesis is that historical and material currents were a constant push and pull on McKay’s decision to travel the globe in search of socialist revolution and resources for his poetry. McKay was born into a middle-class Jamaican family. His father, who came from the peasantry, assembled enough land to give his family an unusual degree of economic security and social capital. James carefully wends through the history of Jamaican capitalism, from the 1865 Morant Rebellion until McKay’s departure from the island, to show how the young poet captured the contradictions of life for poor, mostly landless peasants.

McKay’s interpretation of Jamaican history was informed by readings in Fabian Socialism as a youth, and the “Freethinker” movement on the Island, which made him an agnostic. James gives expert attention to McKay’s early feminist sympathies, deduced from a close relationship with his mother, his proximity to tenacious female peasantry, and his outrage at the plight of prostitutes, partially gathered from a brief and unhappy turn with the island constabulary. By the time he was finished being a cop, McKay’s outrage at the colonial system and sympathies for the oppressed beneath their baton was absolute.

In 1912, McKay left Jamaica for the United States, inspired, oddly, by the example of Booker T. Washington. McKay spent only a few months at Washington’s Tuskegee institute, disdaining its “semi-military, machinelike existence,” before moving to Kansas State Agricultural College. He studied there just two years before leaving again for New York City, a definitive early turning point in his life.

McKay settled in Harlem just as it experienced a huge influx of southern working-class Black and Caribbean migrants. In the latter category were the cast of “Caribbean radicals” that would shape the next stage of McKay’s political development: fellow Jamaican and Universal Negro Improvement Association founder Marcus Garvey; Cyril Briggs, co-founder of the Marxist and Nationalist African Blood Brotherhood, and editor of its journal, The Crusader; and Richard B. Moore from Barbados. But the biggest influence on McKay came from Virgin Islander Hubert Harrison. Although he was a militant socialist, as brilliantly documented by the late Jeffrey B. Perry, Harrison’s biggest impact on McKay was “correcting some of McKay’s residual Eurocentric ideas about Africa,” sharpening McKay’s Black nationalist impulses forged by life under British white supremacy.

The year 1919 was to be a turning point and crucible for McKay: the Russian Revolution of 1917 had already fired his sympathies for Bolshevism, and the first World War his contempt for Western imperial bloodshed. In the summer of that year, Black soldiers returning from the war found themselves targets of racist attacks in cities such as Chicago and East St. Louis. McKay’s poetic fuse ignited in the composition of his Shakespearian sonnet “If We Must Die”:

If we must die, let it not be like hogs

Hunted and penned in an inglorious spot,

While round us bark the mad and hungry dogs,

Making their mock at our accurséd lot.

If we must die, O let us nobly die,

So that our precious blood may not be shed

In vain; then even the monsters we defy

Shall be constrained to honor us though dead!

O kinsmen! we must meet the common foe!

Though far outnumbered let us show us brave,

And for their thousand blows deal one death-blow!

What though before us lies the open grave?

Like men we’ll face the murderous, cowardly pack,

Pressed to the wall, dying, but fighting back!

McKay wrote the poem in a frenzy on the train where he was working as a porter. The first people he read the poem to were fellow workers. The poem exploded in popularity, becoming the equivalent of an anthem for Black rebellions in response to the Red Summer. After first being printed in Max Eastman’s Liberator, it was republished in Marcus Garvey’s Negro World and A. Phillip Randolph and Chandler Owen’s The Messenger. James also points out that the poem has been shared by Jewish victims of Hitler’s camps and Black prisoners in revolt at Attica Prison. McKay himself later expressed shock that the poem had stood for so many: “I am so intensely subjective as a poet … I was not aware, at the moment of writing, that I was transformed into a medium to express a mass sentiment.”

James is at his best in the dialectical method here, showing us quite literally the relationship between literature, artistic consciousness, and “objective conditions.” Meanwhile, the poem helped launch the next stage of McKay’s life when a benefactor gave him money to move to London to help popularize his poetry. As meaningfully, McKay fell in with Sylvia Pankhurst’s Workers’ Socialist Federation in London and became the first (and only) Black correspondent for its newspaper, Workers’ Dreadnought.

McKay covered labor strikes and agitation on the London docks, racism in the English working class, and the Irish struggle, while publishing a number of his own poems in the Dreadnought. He also published his first major public treatise, “Socialism and the Negro,” in its pages in 1921. According to James, the keenest political moment in his relationship to Pankhurst and the WSF was their joint response to E.D. Morel’s “Black Horror on the Rhine” campaign alleging that Senegalese troops fighting for the French during its occupation of the Ruhr valley were raping white women. The campaign was primarily disseminated by the Daily Herald, the newspaper of the British labor movement. Pankhurst was one of the few journalists to point out its racist hysteria. McKay published an enraged letter in the Dreadnought, seeing the event as a strike against class unity: “I write because I feel that the ultimate result of your propaganda will be further strife and blood-spilling between the whites and the many members of my race.” McKay was further galled when the Trade Unions Congress at Portsmouth distributed Morel’s pamphlet to delegates and the Communist Party of Britain endorsed it in 1920.

Despite publication of his first book of poems in England, McKay left for New York in January 1921 a displaced and dispossessed Black Bolshevik in search still of a political home.

“I had looked upon the face of the British nation, fulfilling my boyish wish complementing my education. And I was satisfied that England was a wonderful and perfect place for the English, but no place at all for colored persons, especially black. I left it feeling that I would never want to live there again, nor in any British territory, and I was happily excited to return again to the land of Segregation and Black Lynching. There the life of the spirit at least was more robust against the brute hatred of America than the sepulchral-cold hostility of the English.”

James leaves off his volume here with McKay’s return. His next volume promises to take up the second chapter of McKay’s life up to his death in Chicago in 1944.

On balance, this first volume is likely to be the best political biography we have of McKay’s formative years.

There are for me two political blemishes to the book—one small, and perhaps to be resolved in the second volume, and the second a major failing.

James’s analyses of McKay’s 1921 “Socialism and the Negro” argues that McKay’s support for both the Garvey movement and international socialism was a possible nod to Leon Trotsky’s 1905 theory of “permanent revolution.” McKay’s argument that socialists everywhere should support the Irish, Indian, and Garveyite nationalist movements in order to more quickly bring about the collapse of capitalism, he speculates, may reflect Trotsky’s argument that in “backward” countries, “The bourgeois revolution—carried out by the working class and peasantry because of the weakness of the domestic capitalist class—according to Trotsky, would grow into the socialist revolution.” James states several times in the book that McKay admired Trotsky, without elaborating.

But McKay’s robust support for Black liberation (including the Garvey movement) and colonial struggle suggests that his analysis was likely influenced at least equally by the Bolshevik prioritizing of colonial liberation after the 1917 revolution. Indeed, when he arrived in Russia in 1923, McKay was commissioned by the Comintern to write a pamphlet, published as The Negroes in America, which likely influenced the Comintern’s “Black Belt Thesis” that Blacks were internally colonized subjects. McKay’s Comintern speeches also tended to emphasize self-determination movements in the colonies and in the United States. It would have been helpful if James had fleshed out more fully the influence on McKay’s thinking of both Trotsky and V. I. Lenin, though he does make it clear that McKay had nothing but loathing for Joseph Stalin, denouncing him as an “unctuous tyrant.”

Photo from public domain.

The most troubling political weakness of the book, however, is James’ refusal to engage with and take seriously well-established evidence that McKay was bisexual. Early in the book, describing his Jamaican boyhood, James tells us in passing, “We do know that in subsequent years, after his departure from the island, McKay had heterosexual as well as homosexual relations.” But he never examines McKay’s private life or those relationships. Then late in the book, James reports that the British Foreign Office and Colonial Office took at face value French accusations that McKay was a “sodomite,” without delving into the matter or McKay’s response. At every turn in the book, James seems determined to “straighten” the record of McKay’s life, robustly refuting or ignoring a raft of scholarship and even his own writing that reveals sexuality as an important theme in his life:; For a very recent example, readers can pick up McKay’s recently recovered novel Romance in Marseilles, which features openly queer characters, and was rejected for publication in McKay’s time.

James’s omissions are more than a missed opportunity. McKay was part of a vibrant Harlem Renaissance and “New Negro” movement in which queer Black sexuality flourished. State surveillance, social repression, and forced exile of gays and lesbians has become an important part of our understanding of why writers like James Baldwin ended up in Paris. Aaron Lecklider’s 2021 book Love’s Next Meeting: The Forgotten History of Homosexuality and the Left in American Culture also helps to fill in the record of queers and the Left. I hope that James’s second volume will look Claude McKay and this wider history more squarely in the face. Part of the challenge for Marxists seeking to recover and rebuild the struggle for socialism is illuminating and celebrating all the shades of red in its spectrum.

Featured Image credit: Photo from Socialist Worker (UK); modified by Tempest.

We want to hear what you think. Contact us at editors@tempestmag.org.

Bill Mullen View All

Bill V. Mullen is a member of the Democratic Socialists of America and the organizing collective for the United States Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel. He is the author of James Baldwin: Living in Fire (Pluto Press) and co-editor with Christopher Vials of The U.S. Antifascism Reader (Verso).