Reflections on the 2020 uprising

On Memorial Day of 2022, I went back to the site to commemorate a battle that had taken place in my own city. It was May 30, exactly two years after the George Floyd Uprising kicked off in NYC, just a few days after his murder and the burning of the 3rd Precinct in Minneapolis. On May 30, 2020, I biked down from my home in Queens to check out the rally gathering at the south side of Prospect Park in Brooklyn. It was an otherwise lovely Saturday afternoon, which felt like a strange reprieve from the black cloud left by COVID-19’s detonation. There seemed to be a return to daily life before the lockdown, as local residents bustled between shops on the main commercial avenues. But the fury culminating in the streets starkly juxtaposed these quotidian activities.

The march launched from Prospect Park into Flatbush, a mostly Black neighborhood with a large West Indian population. The tension between people marching and the cops escalated when I saw folks breaking from the gated areas surrounding the park. As people started to move, I ran into a couple of comrades and stayed by their side. Already deeply traumatized by the increasing COVID-19 infection rate and death toll, I was not ready for what was about to occur. So when my comrades decided to head into the clashes, I hung back on the neighboring streets. They quickly disappeared into the scuffle at the following corner where the cops were kettling and pepper spraying people. The battle was raging on Bedford Avenue, a less commercial area, while I remained on the corner of Church and Flatbush Avenues among pedestrians going about their daily business. I could feel the reverberations of rebellion just one block away.

I had been to the marches for Black lives in 2014 and 2015 following the murders of Michael Brown and Freddy Gray. During that time, taking over streets turned into a cat and mouse game of outsmarting the police swarms that trailed us. We would walk down major Manhattan avenues against traffic so the cops couldn’t follow us with their vehicles. As we marched, we would encounter lines of riot police standing in a military formation. These were mere performances of power that effectively dispersed crowds before we were able to reconvene on neighboring streets.

But on May 30, 2020, the tone was different. I felt volatility and growing anticipation. While I waited to reunite with my comrades, I took shelter on a deserted side street (pictured below).

Here I watched a group of riot cops quickly deploy from an NYPD marked van. And while I couldn’t articulate it at that moment, I knew in my bones that the scale was tipping. The political terrain had broken open and a vying for power was taking place between The People and The State in real time. I saw later on an Instagram story that an NYPD van had been lit on fire somewhere on Bedford Avenue. I watched this brief clip of black smoke ascending into the naked blue sky. I was surprised that I had not seen or smelled the smoke. Perhaps it occurred after I left, or maybe I’d been too dissociated with my senses suspended. Cop cars set ablaze would become a common tactic of the George Floyd Rebellion, which was soaring in the middle of a crisis overhauling the U.S. State at every level. When recounting what I’d seen to my therapist that week, she made an incredibly astute point: What was taking place was not “an event, but a process.”

In the weeks prior, there had been thousands of deaths and an unfathomable infection rate in New York alone. The pandemic had reduced the seething violence of class divisions to their barest form. Working class New Yorkers had lost their jobs overnight, unable to buy food or pay rent. Black and immigrant communities had been hit the hardest by COVID-19 infections and deaths, while the wealthy and aspirational classes fled the city to take shelter in second homes. The city’s and state’s insufficient response to the crisis, the collapse of the healthcare system, COVID’s cruel tearing through public schools, among so many institutional failures, revealed the gutted corpse of the U.S. Establishment. The State had invalidated itself on multiple levels, resulting in millions of lives descending into a bottomless hell.

Within just a few days of the uprising, the City of New York became a militarized zone. On June 2, 2020, Mayor Bill DeBlasio issued an executive order for a “State of Emergency” under the guise of COVID-19 infection risk. His referring to street takeovers and property destruction as “violent acts,” a rationale spouted by politicians all over the country, was ironic at best. The city had mandated Marshall Law, euphemistically referred to as a curfew.

During the first evening, I biked from my house to Downtown Brooklyn. That day, DeBlasio had attempted to appeal to the massive discontent, all the while excusing cops who ran their cars into civilians. It was an act of cowardice put on full display to the several hundred New Yorkers at Cadman Plaza booing and yelling. The police presence was ever increasing, as I biked towards the Plaza. Passing the Pratt Art Institute, I noticed what looked like plainclothes police waiting outside the 88th Precinct. They wore baseball caps, polo shirts, and khakis with bullet proof vests that read “HSI.” I later learned that these were ICE agents hanging out in broad daylight. Every arm of the police state was clearly being deployed. Once I got down to Cadman Plaza, it was impossible to get past the squads of police dispersed around the major intersections. They were in regular NYPD uniforms, as opposed to the intimidating appearance of cops in riot gear. I stopped on a corner and watched them for a few minutes. Many of them were casually standing around chatting with one another. Having grown up in Giuliani’s New York, I wasn’t shocked by seeing a large group of cops. But at this moment, they reminded me of the way I had seen Israeli soldiers in occupied Palestine standing around at checkpoints in full uniform, often armed with assault rifles, passing time in the most ordinary way. Even if the soldiers appeared to be at rest, a military occupation was still in motion. And so when I scanned the crowd of cops, it sank in that the city was under siege. The level of escalation further exposed The State’s firm grip on the city.

However, at the same time, activities of everyday working class people were shifting the landscape. Symbols began to emerge, commemorating the heightened events happening daily. After the notorious bombing of an NYPD van in front of Fort Greene Park, artists reorganized the ashes on the sidewalk to spell out BLACK LIVES MATTER.

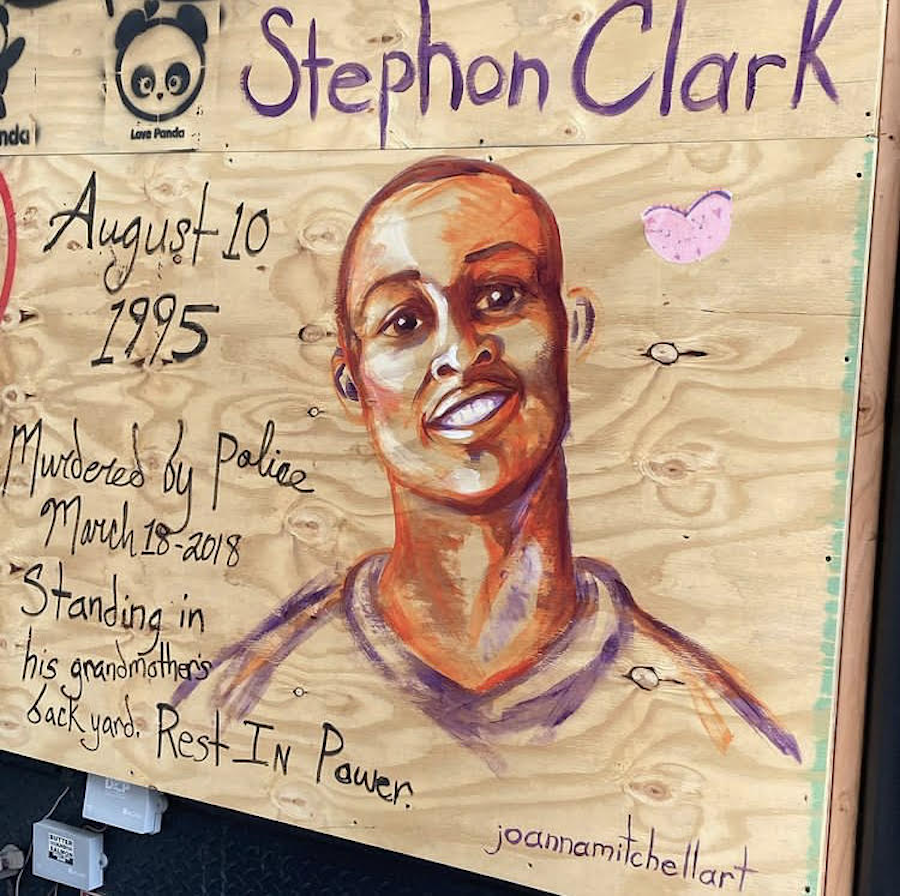

The raiding of SoHo shops in Lower Manhattan had transformed into an extensive art gallery. An area once populated by tourist shoppers had been temporarily expropriated. Artists had painted over the boarded up storefronts with extensive murals. A series of portraits of Black folks whose lives had been taken by police were particularly poignant.

These detailed paintings covering gutted shops articulated an essential message of the Rebellion: defend Black lives over private property.

In the first two weeks of these events, I couldn’t help but think of a line from Mos Def’s song, “Mathematics”: “Why did one straw break the camel’s back? Here’s the secret: million other straws underneath it.” I knew this phenomenon was not merely a spontaneous series of events. Nor was it solely an extension of the Black Lives Matter uprisings of several years before. The existential struggle for Black lives was part of a larger historical continuum that extended beyond my own lifetime.

I gravitated towards Cedric Robinson’s titanic text, Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition. While there is much to sift through in this book, Robinson’s claims about the existential significance of Black insurrection and the possibilities it is capable of bringing forth are worth noting. He describes these activities throughout history—from slave rebellions to marronages—as expressions of metaphysical systems unbound to the concept of private property (Robinson, p. 168). Robinson calls this “the ontological totality,” in which the Black Radical Tradition, which is more pluralistic than its term, presupposes new ways of being. Robinson explains, “The Black Radical Tradition cast doubt on the extent to which capitalism penetrated and re-formed social life and on its ability to create entirely new categories of human experience” (Robinson, p. 170). The resistance from African and Black peoples are so potent because they exist on their own terms outside the dialectic between labor and capital. Josh Meyers, whose scholarship focuses on Robinson’s life and work, explains more succinctly that this ontological totality raises the existential question, what does it mean to live? In other words, what kind of life can exist outside the current material conditions?

A revolutionary vision can only grow through the meeting of imagination and actively expanding our sense of what it means to be human. Robin D.G. Kelley highlights the surrealist movement in Freedom Dreams (2000) as an example of this, wherein the surrealists were revolutionary because they sought to birth “new social relationships [and] new ways of living and interacting” (Kelley, p. 5). In her recent talk at the Socialism Conference 2022, Ruth Wilson Gilmore made a similar point about building “new forms of kinship,” in which human relationships are unbound to the constraints of oppression and exploitation. Abolitionism is the regenerative movement she speaks to that offers us authentic possibilities for living.

The pandemic and the Rebellion have shown us that heightened points of struggle raise the stakes such that we can only rely on what we have: each other. Solidarity is then born in real time when people create a nexus that can withstand the offensive of the ruling class, whether that be cops beating people in the streets, or the boss retaliating against workers. It grows through building organizations that can meet people’s needs, cultivate their political development, and foster collective decision making to execute action, with the objective of taking the offensive position in the class war. These are extremely difficult tasks to execute when the Left has been politically and organizationally limited. The George Floyd Rebellion had altered collective consciousness about police violence and who keeps us safe, but without the amalgamated class power to resist the backlash against the movement.

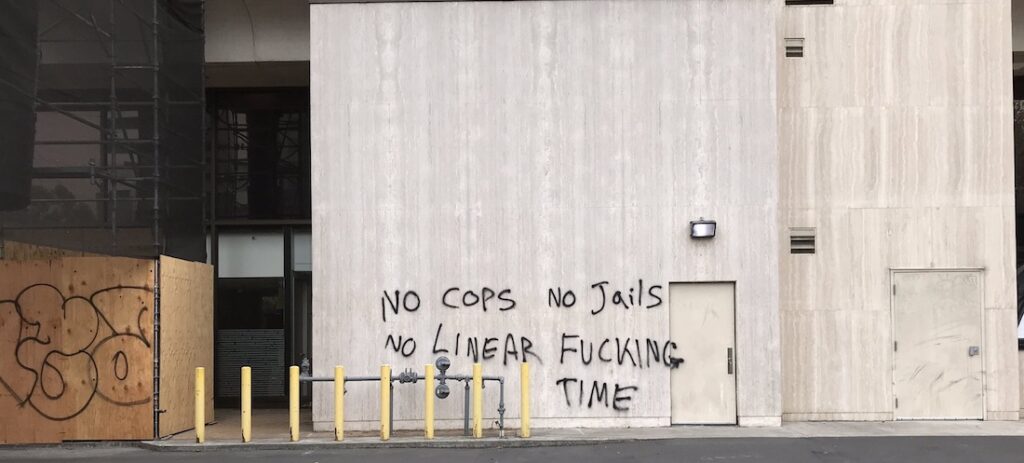

Prior to the uprising, the COVID-19 outbreak had swiftly altered our sense of time. For some, the initial lockdown gave the illusion of time suspended. Meanwhile swaths of essential workers continued doing their jobs. Time shrunk and stretched at strange intervals, obscuring temporality. And then when June came, The Uprising smashed an already broken frame of reference. Millions of people flooding the streets tore through a rippled landscape, where it was difficult to keep up with the course of events. With everything falling apart, the Rebellion was sharply renegotiating the terms of time and space with the police state.

Julie Mehretu’s work excellently represents the way social movements and historical shifts collapse time and space. Her painting “Cairo” consists of a blueprint of Tahrir Square layered with flurries of lines and shapes that sweep across the canvas in all directions.

The relationship between the stark lines, gusts, and streams is not always clear. Some lines fly across space and seem to disappear. Others are more precise, starting and ending at clear points. Some of them intersect, while others pass by one another. All of these delicate abstractions represent the flattening of social activity onto a real, three-dimensional place where there has been ongoing resistance to colonial processes. These phenomena do not come and go through the frame as they might in a video. All of them leave marks on the canvas. Mehretu’s technique of layering materials is also a way of representing time passing. These forms submerge the architectural blueprint of the square, showing the constraints of a colonialist narrative of space. Mehretu’s work can help us visualize the way social upheaval disrupts a seemingly “logical” capitalist order of things, and creates new possibilities for social organization.

In the wake of the George Floyd Rebellion, there was the question of where this could go in the immediate term. What would happen to these embers of revolutionary fervor that were so readily co-opted by liberal political discourse? What kind of organization could come out of this? The latter question seemed to reiterate the framing of revolutionary processes as a linear trajectory. In movement spaces, we often hear descriptions of “a path forward” to socialism. There is even a history of Communist organizations naming themselves in these terms, like Peru’s guerrilla group Shining Path (Sendero Luminoso). But given the disjointed ways in which historical phenomena occur, whether they be the George Floyd Uprising or the Arab Spring, it is impossible to grasp all the strands simultaneously. These events reorient social life and how we see ourselves within the broader scheme of things.

Robin D.G. Kelley wrote in his re-appraisal of Black Marxism that Black revolt reorients temporality. He refers to “blues time,” which comes from Clyde Woods’ exposition of the blues as epistemology in Development Arrested (2017). According to Woods, blues epistemology developed as a form of living and social thought rooted in African American communities in the South (Woods, p. 29). The blues emerged as an ontology, or system that deals with the nature of being, which anchored these communities in their resistance to plantation capitalism in its different forms (2017). Kelley explains that regarding temporality, “blues time eschews any reassurance that the path to liberation is preordained.” There is no definitive trajectory or deliverance from capitalism. But how do we make sense of struggle when we’re in the midst of it? If we took a page from Julie Mehretu’s practice, we could sketch these out on a canvas, and maybe identify the points of intersection where these seeds have been able to grow. Perhaps gazing at struggle as a landscape upon which we traverse might help us grapple with the threads that seem to slip through our hands as we juggle the many tasks necessary to keep things going.

Featured Image Credit: Photo by andres musta; modified by Tempest.

Categories

We want to hear what you think. Contact us at editors@tempestmag.org. And if you've enjoyed what you've read, please consider donating to support our work:

DonateMara Chinelli View All

Mara Chinelli is a writer, educator, and rank-and-file organizer living in New York City.