The Vietnam War in comics, after the war

Since the end of the Vietnam war, comics creators and publishers have explored the war in several ways, from autobiography, horror, war stories, and even superheroics. The old propagandistic stories of the 1960s never returned, although some pro-war messaging can be detected in titles that came afterwards such as The ‘Nam or Dong Xoia, Vietnam 1965. Like other artistic and cultural products of the last decades, comics also reflected the highly contested memory and meaning of the Vietnam War.

Marvel Comics

Marvel, who published more about the war than any other publisher, had a complicated relationship with the war. The Iron Man character was born in the jungles of Vietnam, but after U.S. troops withdrew in 1973, he returned only once—although there were two flashback stories detailing previously unseen Iron Man adventures during the war. In Iron Man 68 (June, 1974) the superhero is in Vietnam searching for one of the supporting characters, Marty March. Surveying a bombed out village, Iron Man remarks “I used to be really proud of my support for the war, but things like this first hand really fog up one’s thinking. Well, I’m sure of this: It’s no longer Tony Stark’s war.”

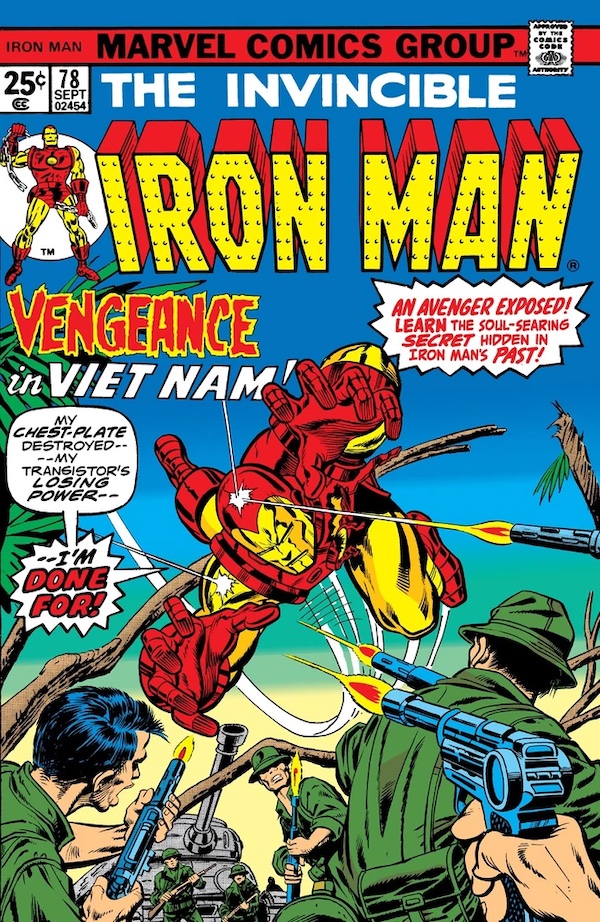

This installment was followed up by the unusually remorseful anti-war story “Long Time Gone” from Iron Man 78 (September, 1975). Billionaire industrialist Tony Stark muses to himself that “As Iron Man, you beat the Commies for democracy without questioning just whose democracy you were serving” and says of Vietnam, “What right had we to be there in the first place?” This prompts a flashback to a time when Stark built a weapon for the U.S. Army that resulted in the destruction of a village full of civilians in Vietnam. The story ends with a present-day Iron Man renewing his vow to no longer manufacture weapons. The issue itself is “Dedicated to Peace.” The second Iron Man Vietnam flashback, from Iron Man 144 (March, 1981), is less overtly political, featuring the superhero saving a downed helicopter pilot shortly after his origin story. Jim Rhodes, the helicopter pilot in question, would later serve as Iron Man and after that as the superhero War Machine.

Additionally, Marvel published one of the longest lasting Vietnam war comics, The ‘Nam, which launched in December 1986 with an original creative team of writer Doug Murray (a Vietnam veteran) and illustrator Michael Golden. Murray had attempted to pitch Vietnam war comics in 1972 but found his scripts rewritten to take place in the less controversial World War II. The commercial environment of the 1980s, after the releases of films set in the Vietnam War like Coming Home, Apocalypse Now, and Deer Hunter would be more hospitable to such stories. Marvel even revealed in a 1987 Comics Interview article that they asked comic stores to position the title on display near the American flag to take advantage of potential buyers’ patriotic sentiment. The ‘Nam was a smash hit for Marvel, and the series inaugural issue actually outsold the ever popular Uncanny X-Men that month. The ‘Nam was also nominated for a Kirby Award for best new series. While the president of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund expressed skepticism asking “should Vietnam really be the subject of a comic book?”, the Vietnam Veterans group the Bravo Organization cited the comic as the best media depiction of the war, surpassing Oliver Stone’s film Platoon. Across the Atlantic, British comic book writer Pat Mills was more critical in a 1987 Escape review writing “For all its sincerity, The ‘Nam is glamorizing war and in a more insidious way than the clearly gung-ho Rambo and Green Berets. The ‘Nam uses the same techniques as war movies like The Longest Day. War is hell, but it’s exciting and just.”

The series was a departure from Marvel’s usual fare in a few respects. For one, the plot advanced in “real time” with a month passing between each monthly issue. For another, superheroes were eschewed, focusing entirely on the realistic trials and tribulations of ground level soldiers. Despite this, the series still had to abide by the censorious Comics Code Authority and therefore could not include the violence and profanity that accompanied the real life war.

While Murray promised that the series would not grind political axes and present a balanced view of the war, and while some critics labeled the series as anti-war, pro-war messaging is evident in the pages of the comic. Already in the “‘Nam Notes” (a glossary of military terms from the war that appeared at the end of every issue) of The ‘Nam 2, the National Liberation Front, or Viet Cong, are clearly labeled “the bad guys,” thereby marking the United States as the good guys. In The ‘Nam 9 the example of Buddhist monk Thich Quang Duc’s self immolation to protest the South Vietnamese treatment of Buddhists is reframed in the letters section to be a protest against Communism.

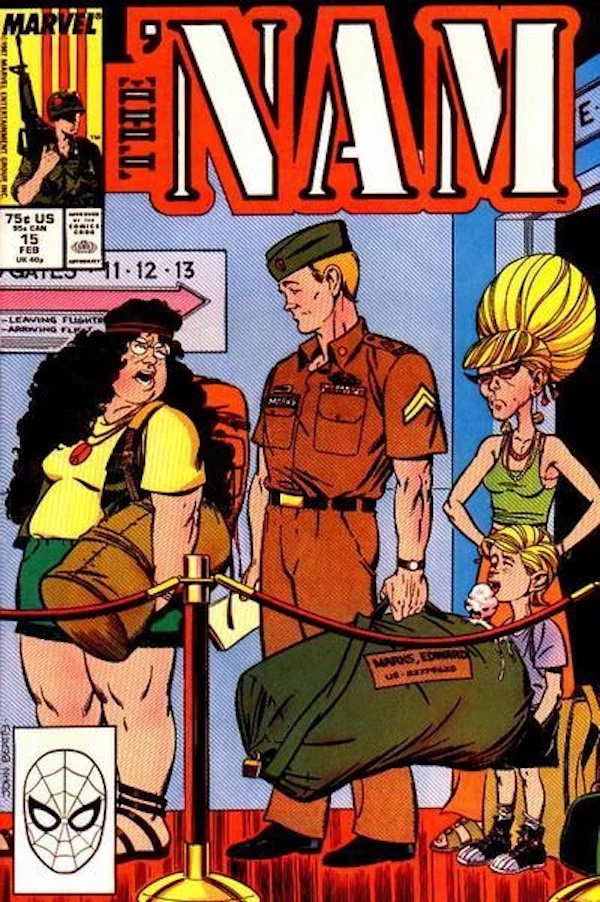

The most sustained example of these messages came in The ‘Nam 15 (February, 1988). The cover features main character (and author stand-in) Corporal Eddie Marks looking down disdainfully at an overweight female hippy wearing a peace sign necklace, an obvious personification of the anti-war movement. The woman’s mouth is wide open, presumably to chastise the hero for participating in an immoral conflict. Within the interior, Marks forcefully argues for the use of napalm in the war after seeing protests against Dow Chemical, and later expresses pride that one soldier who is discharged for incompetency still wants to fight in Vietnam while others are burning their draft cards. A later example can be found in The ‘Nam 24 (November, 1988) in which the infamous “Saigon Execution” photo during the Tet Offensive is reenacted with the cameraman being blamed by the troops for putting it on “the front page of every newspaper in the States” and thereby turning public opinion against the war. Finally, in The ‘Nam 26 (January, 1989) Marks gets in an argument with an anti-war college professor, who is caricatured as a liberal egghead, while attending Columbia University (itself a bastion of Left thought and organizing during the time of the war). When the professor interrupts Marks to say, “There’s still no reason for us to be there. …Think of what we can do with all the money that’s being wasted on guns and napalm,” Eddie snaps his pencil in frustration at the perceived cluelessness of the anti-war side.

Reader response to The ‘Nam was similarly pro-war. Readers praised the comic’s “realism,” positively comparing it to the more overt propaganda of Rambo or Missing in Action. In 2011’s the Reagan Rhetoric writer Toby Glenn Bates curates readers’ pro-war reactions in the chapter “Reagan, the Vietnam Veteran, 1980s Television, and Comics.” The readers’ letters say things like “Until Reagan goes back in time and changes ‘the Nam’ so we would’ve won Make Mine Marvel!” and “If you guys could only come up with ‘Invasion of the Conservatives” starring Captain Ronnie”. One veteran opines that “we weren’t allowed to win” in Vietnam. When a letter writer wrote in to complain about the series’ treatment of anti-war protestors in issue 15, Murray responded “It was people like you who made the Vietnam vets’ homecoming the shame that it was”.

Despite an initial burst of enthusiasm, sales on The ‘Nam began to slip and there were shuffles in the creative team. Penciler Michael Golden left after issue 11, and Doug Murray was replaced by Don Lomax and later Chuck Dixon due to Murray’s reluctance to include superheroes in the title and Marvel’s insistence that the title should be more action oriented. In a bid to increase sales, the vigilante Punisher character was included in two story arcs that play out like comic-book versions of Cannon action films, which are considered to be low points in the title even by fans of the series. Doug Murray’s stories in the title may not have always been agreeable, but they at least felt honest, whereas the later stories felt like nothing more than cheap cash grabs. The crossover gimmick failed to increase sales and The ‘Nam was canceled in September, 1993.

The licensed action-figure-based Marvel title G.I. Joe, written by Vietnam veteran Larry Hama, also addressed Vietnam. The final issue of the title, G.I. Joe 155 (December, 1994) featured the story “A Letter From Snake Eyes” in which the heroic ninja Snake Eyes relates his war experiences to a teenager thinking about joining the military. While framing the war through the experiences of a ninja action hero can come across as ridiculous, and the story also includes the urban legend that returning Vietnam vets were spat upon, the story is not chest thumping propaganda as Hama explains the many downsides of war and military service. One reviewer described the comic as “a story of a soldier who stayed in Vietnam simply so his brother wouldn’t be sent to the front; another who kept signing up trying to finance medical treatment for his father.”

In 2003, Marvel depicted the Punisher’s time as a Marine in Vietnam in the miniseries Born written by Garth Ennis and illustrated by Derrick Robertson. Born was released under Marvel’s “adults only” MAX line and the title takes full advantage of that freedom. Darrick Robertson’s cartooning, used more humorously in Transmetropolitan or the regular Punisher series, is pushed into nightmarish grotesquery, depicting gruesome violence, rape, drug use, and apocalyptic battles. The war is described in narration as benefiting a beast that “has many heads, and on its heads are written names: Lockheed. Bell. Monsanto. Dow. Grumman. Colt. And many more.” The protagonist Private First Class Archie Goodwin is a white soldier who believes that the war is an aberration from the United States that he knows. His friend, who is Black, corrects him, explaining that the war is a logical extension of U.S. policy, going back through the Indian Wars and the slave trade. While this was not one of the stories cited by the right-wing Free Republic in 2004 to prove that the Punisher was a “hate America” character, the publication did cite a later story also written by Ennis in which the Punisher says “I’m not going back to war so Colt can sell another million M-16s. I had enough of that in Vietnam.”

Garth Ennis teamed with artist Goran Parlov to reimagine Marvel’s resident war character, Nick Fury and his service in Vietnam. In my previous article, I mentioned that Sgt. Fury and His Howling Commandos Annual 3 (August, 1967) featured the crack team of World War II commandos being ordered by President Johnson to destroy the North Vietnamese atomic bomb and Haiphong. Ennis and Parlov’s Fury: My War Gone By is as far from that characterization as possible. In the story, Fury serves as a cloak-and-dagger man for the U.S. empire during the Cold War. The story is told by a drunk and regretful Fury who questions whether the work he did in Cuba, Vietnam, and Nicaragua was justified. Fury himself describes the Vietnam War as “the greatest American fuck-up of all time.” In an arc set in 1970 and running from Fury: My War Gone By 7 through 9 (February-April 2013), Nick Fury and Frank Castle (a.k.a. The Punisher) are sent on a covert mission by the CIA to assassinate a North Vietnamese Army general because of the threat he allegedly poses to U.S. forces. However, the real reason is that this general has uncovered evidence of the (real-life) CIA drug trafficking that went on during the war, and the CIA men want him silenced. One reviewer said the title will give readers a “healthy amount of hate for the Iron Fist of Democracy.” Both Born and Fury: My War Gone By Ennis and his collaborators depict American foreign policy as high minded idealism that serves as a mask for naked self interest and war profiteering.

In 2019 Marvel even retconned its characters out of participation in the Vietnam War, instead maintaining that characters like the Punisher, Iron Man, and Mister Fantastic all participated in a war within the fictional southeast Asian country of Sian Cong. This is at the same time that Marvel has allowed its trade paperbacks of The ‘Nam to go out of print, with copies fetching inflated prices.

DC Comics

In contrast to the potentially critical depictions in Marvel comics, DC comics followed the same pattern as they had before the war in depicting Vietnam, namely to show it as little as possible. One exception was in Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ Watchmen 2 (October, 1985), in which the increasingly dystopian United States wins the war with the aid of the God-like superhuman Dr. Manhattan, and colonizes Vietnam as the 51st state. Another was in Hellblazer 5 (May, 1988), the horror title starring British warlock John Constantine. This story depicts the small town of Liberty, Iowa, whose young men fought in Vietnam and were all declared M.I.A. Throughout the story, perspective shifts between the present day in Liberty and 1968 in Quang Tri Province in Vietnam. The townsfolk turn to a televangelist who promises to return “their boys” to them and this promise is fulfilled by returning the soldiers, who then proceed to reenact the war crimes they committed in Vietnam against the Vietnamese on their fellow White Americans, thereby bringing the war home. The story concludes with John Constantine, barely having escaped a massacre, reacting with bemusement at a video store display advertising jingoistic war films that claim to show Vietnam “as it really was.”

Joe Kubert, famous for illustrating war stories including Sgt. Rock and Enemy Ace, wrote and drew the DC graphic novel Dong Xoai, Vietnam 1965 (May, 2010). Kubert had previously drawn the newspaper comic Tales of the Green Berets during the war before leaving because he felt the scripts were becoming too pro-war. He also worked Vietnam War themes into the World War II titles he edited for DC and was editor when these war stories began ending with the admonition to “Make War No War.” Dong Xoai, Vietnam 1965 is done in pencil only, with no inking or coloring. Speech balloons and panel borders are also excised. The lack of speech balloons makes it difficult for readers to determine who is speaking in each scene and makes the characters blend together. The plot is a fictionalization of a real-life battle involving Army Special Forces. The method of telling the story is unique, but despite Kubert’s protestation that the book was “apolitical”, the tone is closer to “rah rah” patriotism of earlier war comics.

Other depictions of the war would be found solely in DC’s creator owned Vertigo imprint, such as Garth Ennis’ Preacher or Jason Aaron’s miniseries Other Side. In Preacher the main character Jesse Custer’s father was a Vietnam veteran and two stories are dedicated to flashbacks detailing his military career, Preacher 18 (October, 1996) and Preacher 50 (June, 1999). These two stories are less critical of warfare than Ennis’ other Vietnam era comics and resemble the British war comics he was a childhood fan of, like Battle. Both focus on the brotherhood and shared loyalty of Marines “Texas” and “Spaceman” as they attempt to make it out of the war alive. The first story contains a scene where the heroes frag a fellow Marine whose negligence got one of their friends killed. The second details how Jesse’s father, “Texas,” came to win the Congressional Medal of Honor by dragging a wounded “Spaceman” through enemy lines and inadvertently foiling an NVA attack. There are a few scenes of anti-war criticism from Spaceman in both stories who says the Marines got home to find they “were fightin’ for politicians and the motherfuckers in the arms industry”.

Jason Aaron, who wrote Other Side, is the cousin of Justin Halford who wrote the Short Timers, which inspired the film Full Metal Jacket. Aaron also cited his cousin’s writing as an inspiration for the work. The comic, DC’s first Vietnam war comic since the Captain Hunter stories in Our Fighting Forces, is unique in that it presents two viewpoint characters on opposite sides of the war, an American draftee and an NVA volunteer. Illustrator Cameron Stewart additionally went to Vietnam to do visual research for the series. The story contains elements of surreal horror, amplified by Stewart’s gory illustrations. Aaron’s attitude towards the war is equivocal as he openly states it’s up to the readers to decide which of the protagonists, if any, is heroic.

The “independent” comics

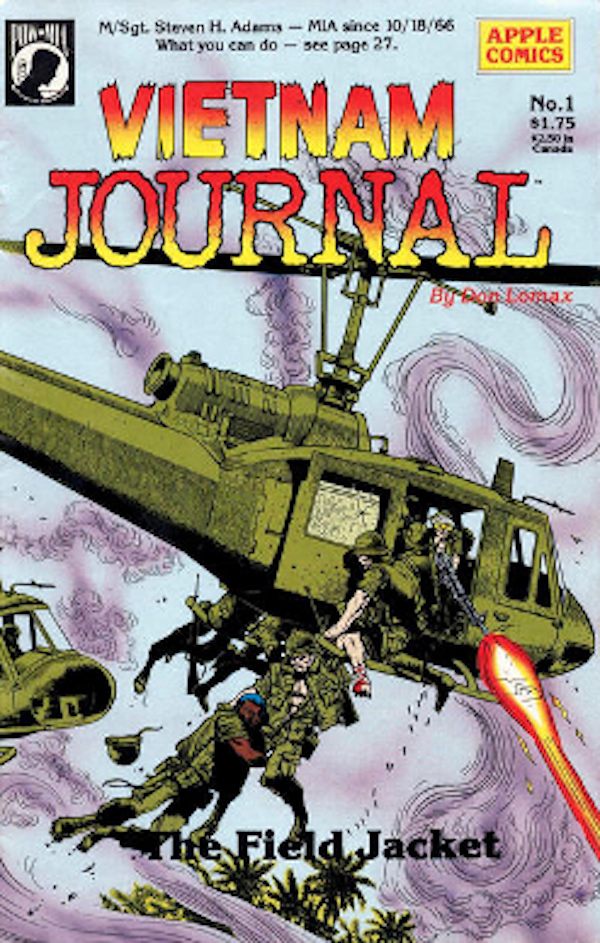

Apart from Marvel and DC, there have been independent comics that have depicted the Vietnam War, the longest lasting being Vietnam draftee Don Lomax’s Vietnam Journal beginning in 1987. Lomax wrote and illustrated the black-and-white book that began at Apple Comics and was unhampered by the Comics Code, allowing him to depict profanity, drug use, and violence uncensored. The stories contain several unflattering depictions of the anti-war movement. The first story, “The Field Jacket,” includes one returning veteran being killed by an anti-war protestor throwing a brick. There is a later story where anti-war hippies attack a veteran in a wheelchair and there’s also a textual reference to “arrogant young pukes” spitting on returning veterans, another reference to the urban legend. However, in a 1990 interview with the Comics Journal, Lomax said that he sympathized with the peace movement, even if he felt they were unfair to returning G.I.s. Other stories focused on the unreliability of the M16 rifles, CIA drug smuggling, fragging, and the disdain officers showed towards enlisted men. The series also endorsed the POW/MIA movement by prominently featuring the movement’s logo on every cover, the belief that Vietnam continued to hold American servicemen prisoner after the Paris Peace Accords were signed in 1973. When Lomax began writing The ‘Nam for Marvel, the logo began appearing on that title’s covers as well. While Vietnam Journal differed in content from the ‘Nam in terms of how explicit it could be, it shared a political thrust that was hostile towards both the anti-war movement and the media, who are characterized as being either sensationalistic or as deliberately undermining support for the war.

Eclipse Comics published two issues of the anti-military Real War Stories in 1987 and 1991 with assistance from the Central Committee for Conscientious Objectors. The title’s talent included Alan Moore, Mike W. Barr, Brian Bolland, Bill Sienkiewicz, and even The ‘Nam artist Wayne Vansant. The stories within are a synthesis of underground comics and oral history. One story, “Tapestries” by Moore and illustrated by Stan Woch and John Tottleben, details Vietnam Veterans Against the War member W.D. Erhardt’s wartime experiences, as well as the lies he was told to get him to join and his difficulty adjusting when he came home from the war. In a 1987 interview with The Comics Journal Moore situated his contribution as a critique of “war mongering aspects” of contemporary comics, saying that it would make him feel like he’s “redressing the balance in a positive way.” The series was sued by the Department of Defense to stop publication because the Pentagon claimed that the one story was inaccurately depicting the U.S. Navy by including a brutal hazing practice of “greasing”(rape via the barrel of M3 submachine gun or “grease gun”), which the Navy claimed did not exist.The Department of Defense ended up withdrawing their lawsuit when the Navy’s own records proved that “greasing” did in fact occur.

In July 2000, Dark Horse comics published comic book legend Will Eisner’s graphic memoir Last Day in Vietnam that, despite its title, also includes stories from the Korean War and World War II. Eisner has a unique connection to Vietnam since he, as a civilian Pentagon employee, created the comic book instruction for the M-16 rifle. The longest story is autobiographical told from a “first person” perspective where Eisner is given a tour of a military base by a Major who is glad to be on his last day in Vietnam, only for the base to come under attack. The Major, along with the General the reader meets, are characterized as being comically ignorant. The Major has never seen combat but is completely in favor of the war to the point of suggesting using nuclear weapons on Hanoi. He also uses a racial slur to refer to the Vietnamese and is confident in American victory. The General mistakes Eisner for a reporter and wants to ensure that his name is spelled correctly in the newspaper. Contrastingly, the combat troops in the field are depicted as zombie-like complete with thousand yard stares, thus showing the dehumanizing effects of warfare. The other, shorter, Vietnam era stories handle a balance between tragedy and comedy, sometimes turning on a dime from one to the other.

Early post-Vietnam war comics, such as the Iron Man stories were contrite and remorseful about the U.S. role in the war. During the 1980s, a time of conservative ascendancy, comics like the ‘Nam and Vietnam Journal that denigrated the anti-war movement and attempted to rehabilitate the war effort to cure “Vietnam Syndrome” (the perceived reluctance of the public to support war). This vision was contested by some comics, like Real War Stories. By the 1990s and 2000s critical voices in comics increased, as the collapse of Soviet Communism made previous artistic attempts to refight the war superfluous. Comics were and continue to be a site contesting visions of what the war in Vietnam meant, both during the war and afterwards.

Featured Image Credit: Photo from VCU Libraries, Vietnam Journal, No. 1, Nov. 1987. Bill Kinsey Comics Book Collection, modified by Tempest.

Categories

We want to hear what you think. Contact us at editors@tempestmag.org. And if you've enjoyed what you've read, please consider donating to support our work:

DonateHank Kennedy View All

Hank Kennedy is a Detroit area socialist, educator, and longtime comic book fan.