Queer liberation and socialism

Learning from the stories of a movement

LGBTQ rights and liberation have only ever been won through struggle. Many of us are familiar with the queer liberation narrative that starts with Stonewall in 1969 and ends with marriage equality in 2015. There is a great deal of militant history before and after that period, however. Every wave of struggle around sexual and gender liberation has involved radicals who made the movement more militant and more revolutionary in its ideologies and tactics.

Queer liberation did not begin with Stonewall. There is a vibrant, compelling, and complex history of brilliant and brave struggles for queer liberation from the mid-twentieth-century forward. LGBTQ rights and liberation organizations have debated differences in ideology, tactics, and politics. These tensions—along with economic decline, right-wing backlash, and the capturing of queer politics by an opportunistic Democratic Party and an electorally and legally focused mainstream LGBTQ organizations—undermined movements developing militant tactics to win significant change.

We can learn from these movements about how to rebuild revolutionary queer liberation struggles. In this article, I recount the stories of activists across the history of organizing for the rights and liberation of LGBTQ+ (queer) people in the United States and review the history of queer liberation activism to explore how our struggle today is tied to a revolutionary socialist project.

Early homophile and communist movements

The industrial era brought gays and lesbians together as city streets opened narrowly to gay society from San Francisco to New York. LGBTQ communities gathered in places like bars and bathhouses—and, in a hat tip to the Village People, the YMCA. Paradoxically, prohibition and the underground, mafia-led bar scene facilitated covert queer socializing. World War II brought men and women together in sex-segregated environments enabling the exploration of gender and sexuality as never before. However, homosexuality was widely regarded as a sin, a derangement, or a crime—or all of the above—and queers lived lives of isolation, secrecy, and persecution. At the same time, the Kinsey Report on male sexuality and Donald Cory’s (pen name of Edward Sagarin) Homosexual in America challenged medical and pathological models of homosexuality. The homophile movement, represented by the Mattachine Society and the Daughters of Bilitis, brought gay men and lesbians, respectively, into social and political activity on their own behalf.

Communism also informed emerging queer liberation struggles. In the 1930s and 1940s, Harry Hay, a member of the Communist Party, was active in the LGBTQ struggle through the mid-century, all the while attempting to win people to a class analysis of oppression. He argued that the revolutionary tenets of communism could be applied to homosexuals in so far as gays and lesbians could be regarded as an oppressed minority struggling for self-determination. Hay famously attended a Halloween costume party dressed as “the demise of fascism.” Sharing the experience of oppression was a source of identity, culture, and politics. Hay noted, “We were in love with each other and each other’s ideas.”

Eisenhower’s 1953 executive order barred “sexual perverts” from federal employment. Thousands were fired in shame. During the simultaneous Red and Lavender scares—in which homosexuals were persecuted as potential communists and/or security risks—the homophile movement defended the individuals targeted by these attacks.

Mattachine was a secret homosocial organization for men that began in 1950 in Los Angeles. The name “Mattachine,” according to several sources, comes from the name of a Renaissance French insurrectionary dance. Harry Hay, Rudy Gernreich, Chuck Rowland, and Bob Hull—as historian Linda Hirshman describes them, “three communists and one fashion icon”—began to meet in private homes, complete with the Daily Worker strewn on the sofa. After two years, Mattachine had spread across the country.

When one of its members, Dale Jennings, was arrested for public indecency after being entrapped by the police at the Los Angeles’ Westlake Park (today MacArthur Park), the group decided to fight on his behalf. Hay convinced Jennings to have a jury trial, as it was common for homosexuals to plead guilty in these cases to avoid public scrutiny. They distributed thousands of leaflets reading, “NOW is the time to fight. The issue is civil rights.” The leaflet asked readers to ask themselves what they would do if facing a similar situation. Jennings’ jury deadlocked—with only one juror thinking he was guilty—and Jennings was free. In his ten days in court, Jennings had admitted openly to being a homosexual. It was the first time an “admitted” homosexual was exonerated of the charge of lewd conduct.

The historic victory led to the further proliferation of the organization across California and in St. Louis, Chicago, and New York. At its beginning, Mattachine was focused on mass action and the mobilization of a large gay constituency who saw themselves as proud members of an oppressed class.

Hirshman recounts an exchange between Hay and fellow Mattachine member Chuck Rowland. Rowland had attempted to become a communist, and he sympathized with the Party’s revolutionary goals. He said, “To most Americans, Communists were wicked, horrid people. But the so-called liberals sat around and talked about socialized medicine, integration, and rights of women. The Communists, on the other hand, were out there on the barricades or picketing or closing down something—doing something instead of just talking.” However much Rowland appreciated the communists, though, he added, “Joining the Communist Party is very much like joining a monastery or becoming a priest. It is total dedication, twenty-four hours a day, 365 days a year. I thought I wanted that, and I did for a while, but I realized I was getting very little sex.” (Priorities. Just saying.)

So, he told Hay, who had been expelled from the Communist Party, we’ll just have an organization for gays. But Rowland and Hay were both frustrated: “What’s our theory? We need a theory! Harry said, we’re an oppressed cultural minority.” Agreeing with Hay, Rowland said, “The other gays don’t want to be an oppressed minority; they want to be like everyone else, except for what we do in bed.”

This debate over identity and difference was a current in the organization. An unidentified Mattachine member was disturbed by an organization meeting announcing the topic “What do we do with these effeminate queens and these stalking butches who are giving us a bad name.” This member told Eric Marcus, “I got very angry at this attack and I finally blurted out this story about the first time I went to a gay bar in 1943. … The first view I got of my brothers and sisters was when about twelve drag queens and twelve butch numbers were led out of the bar by the police. All of the butch numbers were looking guilty, and practically all of the queens were struggling and sassing the cops. I felt so good when I heard one of the queens scream at the policeman who was shoving her, ‘Don’t shove, you bastard, or I’ll bite your fucking’ balls off!’ That queen paid in blood. … When I finished that story I said, ‘Look, the queens were the only ones who ever fought.’”

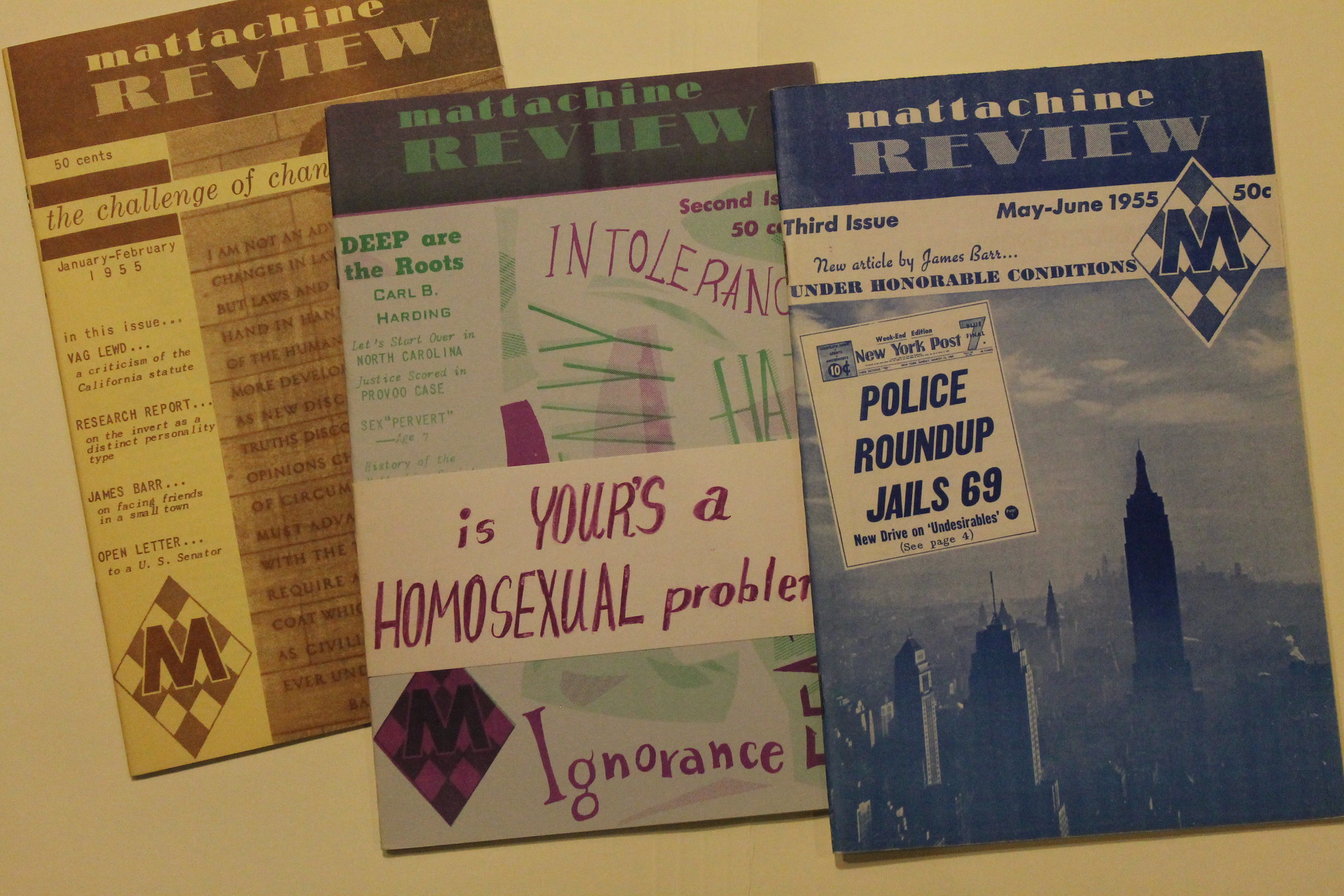

But with the increased visibility of the movement, Hay’s radical politics came under scrutiny. A layer of more conservative Mattachines saw him as a liability. Mattachine in California became more conservative while breakaway chapters in New York and Washington, D.C., challenged the assimilationist factions in 1961. Frank Kameny, a D.C. member, shared Hay’s revolutionary perspective. He and the organization fought his dismissal from the now-defunct Army Map Service, but he ultimately lost in the Supreme Court. He was the first openly gay person to testify before a congressional committee. Kameny published an essay called “The Homosexual Citizen” and, with Randy Wicker, formed the East Coast Homophile Organization (ECHO). Mattachine also put out a magazine called One starting in 1953. A lawsuit against One for salacious content was appealed all the way to the Supreme Court, which ruled in favor of the magazine in 1958. After the split between the coasts, the East Coast groups organized a number of campaigns and actions.

The Daughters of Bilitis (DOB) (named after a lover of the ancient poet Sappho) followed a similar trajectory. Del Martin, one of the organization’s founders, had just lost custody of her young daughter to her ex-husband because of her lesbianism. She and Phyllis Lyon, who became lovers, founded DOB in 1955 in the Castro District of San Francisco to ameliorate their loneliness and sense of isolation. With five other women, they held a first house party, inviting women who were seeking connection, self-understanding, and an antidote to fear. As the decade came to a close, the organization embraced political action. Martin wrote articles in the DOB’s publication The Ladder to protest raids on gay bars and to promote the decriminalization of sodomy.

The DOB took another turn toward the political when Barbara Gittings took the lead. With Kameny from ECHO, Gittings urged an end to decorum and sought action rather than endless talk. They organized pickets at courthouses where their comrades were being tried basically for the crime of existing.

Thus, the homophile organizations were not the uniformly conservative and proper groups that were allegedly displaced by the militancy of the Stonewall era. On the contrary, these groups prepared the way for greater militancy, building the confidence and consciousness of gay men and lesbians who lived in constant fear of arrest, unemployment, the loss of family, and other forms of persecution. To exist in such spaces is political. Without the earlier work of the Mattachine Society and the Daughters of Bilitis, there may have not been a Stonewall to usher out the politics of respectability.

Raids and persecution continued into the following decades, of course. However, the gay liberation movement was increasingly influenced by the anti-war, student, and civil rights movements. Alongside the budding gay liberation movement, feminist movements grew in numbers and confidence. A key figure in the civil-rights movement was the gay leader Bayard Rustin, who played a significant role in the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom and was Martin Luther King, Jr.’s right-hand man in the civil rights movement.

Challenges to the pathologization of homosexuality

Of continuing importance was mounting a challenge to the psychiatric stigmatization of homosexuality. This emphasis was characteristic of the breakaway Washington, D.C., chapter of Mattachine. While the old guard of the Mattachine Society relied upon the sickness model to avoid persecution, Kameny wrote, “The entire homophile movement is going to stand or fall upon the question of whether homosexuality is a sickness, and upon our taking a firm stand on it.”

Frank Kameny became an activist to reform psychiatry, joining forces with psychologist Evelyn Hooker, who had studied gay men in the 1950s to see if their level of psychological disturbance exceeded that of heterosexuals. She concluded that there was no correlation between homosexuality and psychological disturbance. The challenge to psychiatry by Kameny, Hooker, Alfred Freedman, Robert Spitzer (a gay psychiatrist), Kay Lahusen, and others compelled the American Psychiatric Association to remove homosexuality from the list of mental disorders in 1973. The World Health Organization followed suit in 1990.

Meanwhile, universities increasingly became sites of struggle. In 1966, Columbia University Student Bob Martin demanded that the university let the students establish a homosexual club. Martin had been the first openly gay student admitted to Columbia. In response to administrative stonewalling, students occupied space in the basement of a dormitory. The protesters called their new gay lounge “The Allen Ginsberg Center for the Rehabilitation of Straight People.” At one point, a frustrated Marty Manford went into the Dean’s office and started taking furniture from the Dean for the lounge. He also called the news network ABC. The administration gave in. A student activist recalled, “Something was happening. The lion was growing and learning. Columbia was teaching us something. It was teaching us to fight. It was teaching us not to be afraid.”

The work of Mattachine, the Daughters of Bilitis, psychiatric activists, and students had set the stage for the explosion that was coming three years later at Stonewall, which for many activists marks the official beginning of the queer liberation movement. Stonewall also forefronted transgender activists like Sylvia Rivera and street youth.

These organizations and activists were deeply informed and inspired by the civil rights, women’s liberation, anti-war, and student movements—and the near-revolutionary struggles of 1968. The heady moment was ripe for the expansion of movements for civil rights and liberation to include queer people, finding expression in the Stonewall Rebellion.

The Stonewall Rebellion

The Stonewall Rebellion began on June 28, 1969, on Christopher Street in New York City at the Stonewall Inn, a riot that was predated by militant sit-ins by “gender-deviant” youth and sex workers at Dewey’s restaurant, Cooper Donut, and Compton’s Cafeteria. As in the case of the Stonewall, restaurants and bars were sites of safety and organizing for queer people generally and trans people specifically.

The Stonewall Inn was a mafia-run bar that was routinely raided by police. That night, queer people who frequented the bar and its surrounds rebelled against one of these raids, throwing bricks and coins at police, who ultimately barricaded themselves inside the bar, which subsequently was set on fire by protesters.

David Eisenbach describes the militancy of this rebellion against what was not a normal raid. The mafia and the police collaborated to extort money from gay patrons. Throwing coins at police was a symbolic response to this practice. The “morals division” of the police force subjected transgender patrons to genital searches, illustrating the dehumanizing impact of such policing. Marty Manford described the breaking of windows as a “dramatic gesture of defiance” against the police and the “lancing of a festering wound of anger.”

Manford participated in the chants: “Say it clear, say it loud; gay is good, gay is proud!” “Two, four, six, eight; gay is just as good as straight.” “Out of the closets and into the streets!” He commented, “We’re going to get loud and angry until we get our rights.”

The personal accounts of people who were there speak to the process of rapid radicalization that happens at such moments. Martin Boyce, a youth at the time, said:

When it was over and some of us were sitting exhausted on the stoops, I thought, My God, we’re going to pay so desperately for this, there was glass all over. But the next day we didn’t pay. My father called and congratulated me. He said, “What took you so long?” The next day we were there again. We had had enough. Every queen in that riot changed.

Queer insurrectionists then published a manifesto to get cops out of bars. Mattachine, however, reflecting its increasing irrelevance, posted notices calling for quiet conduct on the streets of Greenwich Village.

There were other key insurrections in this period, one responding to the Snake Pit riots in New York, in which an arrest led Diego Vinales, a gay youth, to jump out of his cell window only to be impaled on the spikes in the fence around the police station.

Trans scholar-activist Susan Stryker highlights the transgender base and legacy of Stonewall, explaining that “drag queens, hustlers, gender nonconformists of many varieties, gay men, lesbians, and countercultural types” frequented the Stonewall Inn and other Greenwich Village sites. When the police raided the bar on that day, “African American and Puerto Rican members of the crowd–many of them street queens, feminine gay men, transgender women, or gender-nonconforming youth–grew increasingly angry.” Sylvia Rivera, a revolutionary transgender activist, played a significant role in the uprising. In 1970, Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson founded the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) to aid and mentor queer street youth.

The Gay Liberation Front and the Gay Activist Alliance

After Stonewall, two major organizations were formed. The first was the Gay Liberation Front (GLF), named in solidarity with the North Vietnamese National Liberation Front, signaling radicalism and a connection to the politics of anti-imperialism. Martha Shelley, a member of DOB, was frustrated with the older groups’ growing quietude. She, with others including Jim Fourrat, Bob Martin, Marty Robinson, and Arthur Evans, founded the Gay Liberation Front; they set a late July date for a march, which was the first political action after Stonewall. The march, rally, and celebration were openly militant and anti-capitalist.

Following the example of the Black Power movement, the activists announced an agenda of Gay Power. Bob Martin told Eric Marcus:

What is Gay Power? … It is demanding to be recognized as a powerful minority with just rights which have not been acknowledged; it is an insistence that homosexuality has made its own unique contribution to the building of our civilization and will continue to do so; and it is the realization that homosexuality, while morally and psychologically on a par with heterosexuality, does nonetheless have unique aspects, which demand their own standards and their own subculture.

This was among the first clear expressions of the idea that gays and lesbians not only wanted justice and equality, but also were crafting a separate culture and sense of identity.

GLF’s platform was wide-ranging. It called for free birth control, 24-hour child care, full employment for people around the world; abolition of the judicial system and police; free food, shelter, transportation, health care, utilities, education, and art; abolition of the bourgeois family; and the conversion of heterosexual radicals to homosexuality.

Notoriously, the GLF held marathon meetings without rules or agendas at a space called Alternative U., and organized in a cell structure. One cell was the openly communist Red Butterfly Cell.

GLF mounted a number of hit-and-run protests. They were plagued, however, by internal conflicts over whether they should be fighting for gay rights or in solidarity with others. For example, there was a fierce internal conflict over whether to support the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, whose leadership was fundamentally anti-gay at that point.

Out of frustration with the chaos that was the GLF, the Gay Activist Alliance (GAA) was founded by Arthur Evans and Marty Robinson, among others. The group became notorious for its un-hip adoption of Robert’s Rules of Order in managing meetings with actual agendas.

At the same time, the GAA exhibited militancy, inventing the protest tactic called the “zap”—which we have seen in use in later movements, in the 1980s in ACT UP and in the 2000s by groups like GetEQUAL and more recently in the Movement for Black Lives—in which an organized group of protesters gets access to events where politicians or celebrities are speaking and stage confrontations. For example, the GAA targeted New York City Mayor John Lindsay multiple times, trying to get him to acknowledge and respond to police raids and brutality. Robinson said:

Our view was that it was very important to bring to the surface the deep-down anger and resentment that gays had against the repressive policies of society. It was a process whereby gays had to become aware of gay rights as a political issue. And it was part of the long process of achieving positive self-identification as gays and lesbians. I think time has proven that we did the right thing.

At future zaps confronting the mayor, someone started a refrain that became a regular chant in GAA events: “Answer the homosexuals. Answer the homosexuals.” The GAA zapped the corporation Fidelifacts, whose executives had denigrated gays, saying they knew them when they saw them: “If it walks like a duck and talks like a duck…” So GAA and DOB organized a picket in Times Square; Marty Robinson paraded in a duck costume. “Even in Times Square, the sight of dozens of gay protestors marching behind a giant duck attracted attention.”

GAA zapped the city clerk by sitting in holding gay weddings, complete with cake, in a precursor to similar events in the more recent movement for marriage equality. One member said, “The only way of obtaining a meaningful response is to create a meaningful nuisance.”

One interesting point is that the GAA was the first organization that started using the term “homophobia” after Marty Manford was bashed and seriously injured by the president of the NYC Fireman’s union at a meeting of city bigwigs in 1972. The term was coined in this contest by psychologist George Weinberg, who worked with Frank Kameny. The GAA activists appreciated the concept because it disputed who was mentally ill—not the queers, but the haters.

Contrary to Duberman’s historical characterization, GAA was not the ideological ancestor of the Human Rights Campaign or of today’s corporate Pride events.

Activists moved across organizations depending on their interests. Karla Jay describes going in the same week to GLF meetings and feminist consciousness-raising groups. The GLF’s male members were not “woke” about women’s liberation, and the feminist groups were anxious about lesbianism, but when you put the two together you have something like militant queer feminism, Jay explained.

In fact, the group Radicalesbians emerged from GLF, joining Redstockings and the New York Radical Feminists, among others, in the fight for women’s liberation.

Radicalesbians published a manifesto called the “Woman Identified Woman,” which, among other things, stated, “What is a lesbian? A lesbian is the rage of all women condensed to the point of explosion.” This rage motivated lesbian feminists to take on the mainstream women’s movement as well as corporate and political elites.

Lesbian activists staged a zap at the Second Congress to Unite Women in New York City to protest the exclusion of lesbian speakers from the congress and distributed copies of this manifesto, written by a group that included Rita Mae Brown and Artemis March. The zap involved dozens of lesbian feminists wearing T-shirts reading “Lavender Menace” under their clothes. The reference is to the denunciation of lesbians as a threat to the credibility of the women’s movement, uttered by NOW leader Betty Friedan. In the hall, the activists killed the lights, took off their outerwear, and appeared filling the aisles when the lights came on. The leaders of the congress were not amused.

The 1970s: Radicalism and backlash

The energy of post-Stonewall radicalism carried activists into the 1970s. In the late 1970s, the success of activists in winning anti-discrimination bills at the local and state levels provoked a backlash and the rise of a hardened anti-gay right, epitomized by the campaign led by singer Anita Bryant to undo those reforms and implement anti-gay referenda. Her efforts were successful in places where there were no powerful coalitions of experienced activists to mobilize a response. In California, such a coalition defeated the Briggs Initiative which would have barred gay and lesbian teachers from posts in the public schools.

Where those coalitions were most effective is when the labor movement, including teachers’ unions, was involved. Miriam Frank’s book Out in the Union documents the power that economic leverage can bring to queer struggles and how unions can benefit LGBTQ people by pushing for reforms like domestic partner benefits, health insurance that covers the needs of trans workers, anti-discrimination policies, and mechanisms to grieve these matters. Frank argues that the queer struggle is strengthened by labor’s capacity to reach beyond identity enclaves, while detachment from labor is a weakness in defeating the efforts of the Right to roll back history.

An example of the power of solidarity between LGBTQ struggles and labor was the boycott of Coors Beer. Predating Stonewall, the boycott was initiated by Latinx groups against Coors’ racist hiring practices. In 1973, San Francisco city supervisor Harvey Milk appealed to the Teamsters’ Union to challenge the company’s violations of labor rights and its discrimination against LGBTQ workers.

Gay-labor solidarity was not the only instance of intersectional struggle in the queer liberation movement. Queer liberation organizations and activists were always closely tied to anti-racist and other civil rights movements. Lesbian feminism tied feminist and queer politics together. Black feminists like Barbara Smith and the Combahee River Collective articulated connections among race, class, gender, and sexuality.

Youth organizations in high schools also flourished through the decade as a new generation took the stage. Randy Shilts, who would become the author of And the Band Played On: Politics, People and the AIDS Epidemic, came out in his high school anthropology class in 1972, having met former members of the GLF and GAA. He commented, “In just one week I was able to put the whole gay thing in perspective, to shift it from being my problem to being society’s problem. Gee, I’m all right. It’s society that’s wrong.”

Over the course of this time, both mainstream and alternative media and culture began to provide shifting images and narratives for gay Americans.

ACT UP and the fight against HIV-AIDS

The AIDS crisis interrupted this process. In the 1980s, gay militants were forced to turn their attention to demanding a political and scientific response to the epidemic. Larry Kramer along with several others founded the Gay Men’s Health Crisis, a complex organization providing a range of services that exists to this day. Kramer was a vocal part of the debate over promiscuity, trying to convince gay men to use condoms and reduce their number of sexual partners. For many men, though, sexuality was core to their identity, and these arguments were difficult.

The other debate in which Kramer was embroiled was whether the gay community should care for itself without relying on or trusting outside medical experts or whether they should make demands of the federal government and the scientific establishment.

There were organizations and actions echoing the periods of militancy that came before.

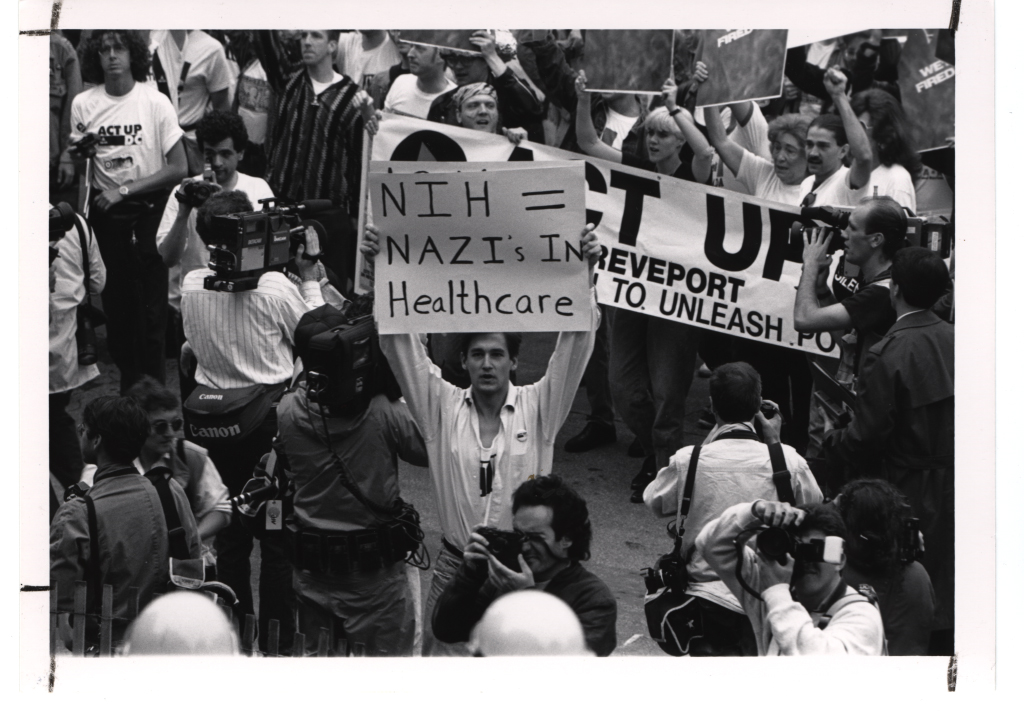

Marty Robinson—remember him?—founded the Lavender Hill Mob which brought zaps to the AIDS awareness movement. ACT UP zapped St. Patrick’s Cathedral, pharmaceutical companies, and politicians; they zapped the New York Stock exchange, chanting, “Release the drugs.” They adopted the powerful and still resonant slogan “Silence=Death” and appropriated the sign of the pink triangle to link the ravages of the epidemic, unaddressed by society at large, to the Holocaust. ACT UP published hundreds of flyers, zines, and statements. An act of civil disobedience on Wall Street demanded the establishment of an immediate coordinated, comprehensive, and compassionate national policy on AIDS. The movement shifted from an emphasis, as in Gay Men’s Health Crisis, on do-it-yourself services for afflicted persons to making demands of the establishment. ACT UP’s efforts were victorious as federal institutions began to respond with inclusive research and treatment.

But by 1988, 82,000 Americans had been diagnosed with AIDS, and 46 thousand of them died. (To this day, more than 37 million people worldwide have died as a result of the virus.) It has been estimated that half of the gay men in New York who were born between 1945 and 1960 were lost. Among them were Bob Martin, Marty Robinson, Jim Owles, Marty Manford, and Randy Shilts.

Even in the context of such loss, there is no doubt that the militancy and constant public pressure of ACT UP were instrumental in finally compelling national institutes and the pharmaceutical industry to respond to the crisis.

Another activist project carries the memory of the struggle against HIV-AIDS: the Names Project AIDS Memorial Quilt. Cleve Jones, who organized alongside Harvey Milk, founded this project, which pulls together thousands of panels representing people who died from HIV-AIDS. Jones went on to play a significant role in the 2000s marriage equality movement.

The Democratic Party and neoliberal gay rights organizations

And then there were the 1990s. An increasingly conservative Democratic Party (represented in the Democratic Leadership Council, or DLC) overtook the gay liberation movement with money- and politics-driven organizations like the Human Rights Campaign. The mainstream movement aligned itself with the neoliberal agenda, arguing for modest piecemeal reform and traditional “family values.”

The 2000s were a decade of lawyers and laws when it came to progress for LGBTQ persons in the U.S. The National Gay and Lesbian Task Force started a number of state-level efforts. Wealthy financier Tim Gill founded the Transgender Law and Policy Institute, and, in general, there was a lot of attention given to attempting to make change in the courts.

The 1986 Bowers v. Hardwick decision of the Supreme Court upheld the criminalization of sodomy. But in 1996, Romer v. Evans upheld the protection of gays and lesbians under the Equal Protection Clause, nullifying an anti-gay law in Colorado. In 2003, Lawrence v. Texas decriminalized sodomy.

The 1990s and 2000s were decades of increased cultural visibility in the mainstream, alternative, and social media. The 2008 election of Barack Obama as president was an unprecedented historical moment, albeit clouded by the punch in the gut that was California’s Proposition 8.

Even as LGBTQ rights organizations turned toward the Democratic Party, Democrats were not consistent allies to queer people. Democrat Bill Clinton implemented the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy prohibiting LGBTQ people from serving openly in the armed forces and signed the Defense of Marriage Act in 1996. Obama’s support for LGBTQ+ citizens was lukewarm. He campaigned with Joe Biden on the policy that marriage is between one man and one woman (from which he later “evolved”). He invited right-wing evangelical Rick Warren to provide the blessing at his inauguration on the very eve of his addressing the Human Rights Campaign Banquet. While he signed the bipartisan repeal of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” and enacted a number of employment and other reforms, he addressed anti-queer violence by signing new hate crimes legislation that increased the power of the criminal justice system. As Laurie Roades explains, the Obama legacy on LGBTQ issues is mixed. Most importantly, struggle was key to pressuring the president and courts to make reforms. The winning of marriage equality in 2015 is the paramount example.

The marriage equality movement

Some queer theorists and activists have criticized the goal of marriage equality as a conservative, “homonormative” demand. However, the right to marry is a class issue: Insurance benefits, tax advantages, the right to inherit, and many other basic provisions accompany marriage in our society. Moreover, the right to marry (including both inter-racial and gender-neutral marriage) recognizes the basic humanity of oppressed people. While revolutionaries seek change beyond equality in existing society, the demand for equality has been central to the major transformative movements in history. For these reasons, the marriage equality movement and victory should be important to socialists.

Marriage equality did not fall from on high as a gift from benevolent judges and politicians. Indeed, there was a liberatory wing to the marriage equality movement that resonates with the memory of the GAA. The organization GetEQUAL (2010-2018) mobilized for reforms like the inclusion of gays serving openly in the military and the right to marry. Yet, in its confrontational tactics, GetEQUAL included the kind of zaps that the GAA invented. Acts of civil disobedience on the part of soldier Dan Choi brought national attention to these issues. GetEQUAL also supported the efforts of trans military whistleblower Chelsea Manning, combining the anti-war and queer liberation movements.

Most importantly, the 300-thousand-person-strong 2009 marriage equality march on Washington was the largest march on the Capitol to that date and a watershed moment for our movement. In 2013, United States v. Windsor overturned the Defense of Marriage Act. And the Supreme Court’s 2015 decision in Obergefell v. Hodges mandated marriage equality on a national scale. Both of these decisions were products of that march and subsequent militant activism.

Lessons for our movement

The stories of these compelling events, people, and groups offer significant lessons for our way forward toward more fully realized queer liberation.

First, liberation is a lifelong and intergenerational project. Queer liberation did not start in 1969 on Christopher Street. It was built out of organizations, efforts, publications, debates, splits, and experiences of all of the activists who came before. The homophile groups were incredibly brave and always political; their members went on, inspired by the militancy of the late 1960s, to build new, excellent, and influential organizations including ACT UP.

Second, as revolutionary socialists, we are not doomed to repeat the tensions and divisions that split these organizations, instead stressing solidarity and common cause in the context of a critique of a broader capitalist system that requires oppression, exploitation, and division.

Martin Duberman, in a recent book provocatively titled Has the Gay Movement Failed?, argues that today’s national LGBTQ movement has chosen equality over liberty and assimilation over freedom and difference; further, he states that the socialist Left does not address the identity and cultural issues around desire, sexuality, norms, and the family. He hesitates to declare victory in our movement’s “assimilationist” agenda of gay marriage and military service. He names the GLF as a forerunner of today’s radical anti-assimilationist organizations and the GAA as the parallel to the HRC.

As I have pointed out, this distinction is not supported by history. Both of the earlier groups and their members were amazingly brave, creative, militant, organized, and successful. Yet, as Harry Hay and Chuck Rowland were trying to work out, we need a theory. A theory not only explains how oppressions operate; it also must explain how they are constitutive elements holding up a system—the system of capitalism.

As Holly Lewis explains, the only kind of political perspective that will be revolutionary with regard to queer liberation and the liberation of all people is one that understands and is responsive to the system as a whole.

In Tempest, we understand queer oppression and all other oppressions in the context of how capitalism needs private families to carry the burden of not only biological reproduction but also social reproduction. In contemporary capitalism, housing, health care, education, socialization, housekeeping, and so on—are all made private responsibilities such that capitalists and the state are off the hook when it comes to social reproduction.

The ability of capitalism to privatize care work so ruthlessly depends upon an ideal of the private family. The GLF knew this and expressed it in their platform: free birth control, 24-hour child care, full employment, elimination of the judicial system and police, free food, shelter, transportation, health care, utilities, education, and art; and the abolition of the bourgeois family.

The social construction of gender roles is key to the justification that families, whatever their composition, must do all of the work of surviving in an increasingly brutal system. Transgressing gender roles and the gender binary, as many feminists and queer people do, threatens to undo this arrangement in reality and in popular consciousness, thereby alarming capitalists and the state who profit from doing as little of such labor as possible. Women’s bodies and reproduction, along with the bodies of trans and gender non-conforming people, are targeted for ideological and physical discipline. The recent attack on reproductive justice and the imminent end of legal abortion are expressions of this impulse.

Thus, as socialists, we believe that intersectional oppressions of gender, sexuality, race, and ability are interrelated on the terrain of capitalism. Oppression functions to divide groups from one another and uses identity categories in order to keep the privatization and exploitation machines functioning. This is our theory. Its logical conclusion is that we need a struggle against particular oppressions as part of an anti-capitalist struggle. In contrast to single-issue movements, we target the system as a whole. We are revolutionary socialists.

We are witnessing the ascendance of a right-wing movement targeting queer people. Florida Governor Ron DeSantis signed a bill–dubbed “Don’t Say Gay”—forbidding instruction on gender identity and sexual orientation in schools. (His efforts echo those of fellow Floridian Anita Bryant in the 1970s. Here we are again.) So far in 2022, there have been more than 300 anti-LGBTQ bills proposed in state legislatures. Even the rightward-leaning Washington Post has called for visible public activism in response to these bigoted laws, citing the historical successes of militant LGBTQ movements.

We must be part of this fight. At this moment, trans and other gender-queer activists inspire us to become deeper on questions of identity, desire, psychology, and struggle. We must continue to develop a truly intersectional program that can explain how oppressions are connected to each other in the service of the imperatives of capitalism and how the ideological and psychological dimensions of oppression are tied to economic exploitation.

Finally, we need an organization that can weather waves of militancy and defeat, one that can learn from backlash, one that can survive periods of retreat without surrender and complexity without dissolution, and one that can build an intergenerational project to end capitalism and replace it with something better. In struggle, there is hope. In revolutionary organization–in the ability to see the system as a whole and learn how to fight it–there is power.

Featured Image Credit: Photo by Ricky Flores; modified by Tempest.

Bibliographic note:

Major sources for the information in this article include David Carter, Stonewall: The Riots that Sparked a Revolution (New York: Saint Martin’s Griffin, 2004), Martin Duberman, Stonewall (New York: Penguin, 1993), David Eisenbach, Gay Power (New York: Carroll and Graff, 2006), Linda Hirshman, Victory: The Triumphant Gay Revolution (New York: HarperCollins, 2012), Karla Jay, Tales of the Lavender Menace (New York: Basic Books, 2000), Eric Marcus, Making Gay History (New York: HarperCollins, 2002), Sarah Schulman, Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987-1993 (New York: Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux, 2021), and Susan Stryker, Transgender History (New York: Seal Press, 2017).

I also recommend Holly Lewis, The Politics of Everybody: Feminism, Queer Theory, and Marxism at the Intersection (London: Zed Books, 2016), Keeanga-Yahmatta Taylor, How We Get Free: Black Feminism and the Combahee River Collective (Chicago: Haymarket, 2017), and John D’Emilio, Making Trouble: Essays on Gay History, Politics, and the University (New York: Routledge, 1992).

Categories

We want to hear what you think. Contact us at editors@tempestmag.org. And if you've enjoyed what you've read, please consider donating to support our work:

DonateDana Cloud View All

Dana Cloud is a Tempest Collective member and scholar of Marxism, popular culture, and social movements currently teaching at California State University, Fullerton.