The left wing of the possible?

Review of A Failure of Vision: Michael Harrington and the Limits of Democratic Socialism

A Failure of Vision

Michael Harrington and the Limits of Democratic Socialism

by Doug Greene

Zero Books, 2022

Michael Harrington (1928–89) is mainly known on the US Left today for two reasons. First, his 1962 book The Other America was, as Doug Greene says, “a groundbreaking and moving exposé of poverty in the United States” (60). Its “call to enlightened liberals for action to rescue the poor” (63) exerted a significant influence on the Kennedy administration and then, more consequentially, on Lyndon Johnson’s “War on Poverty.” By 1965 The Other America had sold more than 70,000 copies and was in its fifth edition. Secondly, in March 1982 Harrington was instrumental in founding, and became chairman of, the Democratic Socialists of America. DSA brought together the Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee that Harrington had led since its founding in 1973 (DSOC brought some 4000 of its members into DSA) and the New American Movement (which had roughly 2000 members at the time).

Harrington’s Reagan-era DSA was different in several respects from today’s DSA—and not only in terms of its size (the financial report submitted to the 2021 DSA national convention claimed almost 95,000 members). As a member of the Rutgers-New Brunswick DSOC/DSA “local” in the late 1970s and early 1980s, I never once heard members call each other “comrade.” Nor was I aware of DSA working groups with the word “revolutionary” in their titles. Although there were student-based contingents at some college campuses around the country, the overall membership of DSA was considerably older then than it is now. Despite these differences, however, the fundamental questions about DSA’s politics remain the same. Although DSA has moved to the left on some issues in recent years, its “overwhelming priority,” as Greene argues, “remains electoral politics”—and ultimately its influence on the Democratic Party. Having voted at its 2019 convention not to support any presidential candidate other than Bernie Sanders, factions of the formal leadership nonetheless publicly advocated for a Biden vote, against the mandate of the DSA Convention. The “dirty break” from the Democrats articulated in a resolution passed at the DSA convention remains, two years into Biden’s presidency, mainly “dirty” and no real “break.” This is the case despite radical activist interventions by local DSA working groups around the country.

It’s clear from the title that Greene’s political biography of Harrington is openly critical—not only of Harrington himself but also of DSA and the entire tradition of social democratic reformism. The book is forcefully written and impressive in its integration of history and political analysis. It deserves to be read not only by revolutionary socialists who will for the most part share Greene’s critical perspective, but by reform socialists and liberals open to learning from the questions he raises about Harrington’s accomplishments and influence. Greene acknowledges Harrington’s abilities as a writer, his astonishing energy as an organizer and polemicist, and his stature within the Socialist International. A Failure of Vision shows that socialists today have much to learn from the contradictions and limitations of Harrington’s career as the best-known U.S. socialist from the early 1960s until his death in 1989.

Harrington was born in St. Louis in 1928, the only child of staunchly Catholic, Irish American, and Democratic parents. He went to Jesuit schools in St. Louis and then to the Jesuit College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts. Following his father’s wishes he entered Yale Law School, which had become “a bastion of unabashed liberalism.” He wasn’t politically active at Yale—though he did become an avid supporter of the Zionist cause in Palestine, a commitment he would retain for the rest of his life. Harrington eventually dropped out of law school and joined the graduate program in English at the University of Chicago. His main ambition at this time in his life was to become a writer. He initially kept his distance from the intense political environment of Chicago of the late 1940s and was, as he acknowledges in his 1973 autobiography Fragments of the Century, drawn to the “Bohemian” culture of the city and a worldview that he himself saw as “distinctively aesthetic and elitist.” (65)

By 1949, when Harrington received an MA in English from the University of Chicago, he had lost his faith in the Catholic Church. He returned to St. Louis and took a job for several months as a social worker in the Public Welfare Department of the public schools. It was this experience, he later said, that drew him into anti-poverty activism. Still restless and attracted to the life of an avant-garde artist, he moved to Greenwich Village in New York, where he took a variety of temporary jobs, wrote poetry, and took part in radical political discussions for the first time. In retrospect, he described this moment in his life as a “spiritual crisis.” Harrington decided to return to the Catholic Church on terms that would substantially influence his subsequent political direction. He took a job writing for Catholic Worker, founded in 1927 by the socialist Dorothy Day and, as part of the Catholic Worker Movement, a notable force on the U.S. Left. This was Harrington’s first opportunity to write for a mass audience. He came to know other prominent New York writers on the Left, such as critic and Partisan Review editor Dwight Macdonald, and began to read seriously in the Marxist tradition.

At a March 1952 protest Harrington met Bogdan Denitch, a Yugoslavian exile from the Nazis who was then a student at the City University of New York and a member of the Young People’s Socialist League (YPSL), the youth organization attached to the Socialist Party of America (SPA). Harrington soon joined the YPSL. He and Denitch, along with other YPSL members, opposed the Socialist Party’s support for the Korean War. Denitch was a strong supporter of Max Shachtman’s Independent Socialist League (ISL), which also opposed the war. In August 1953, along with 37 other members of the YPSL, Harrington and Denitch voted to leave the SPA. The following February they joined forces with Shachtman’s ISL under the banner of the “Young Socialist League” (YSL). According to Greene, despite the ISL/YSL’s small numbers, “Harrington was optimistic that they would lead the forthcoming socialist revolution.” (25)

Harrington credited Shachtman with “introduc[ing] me to the vision of democratic Marxism” and to the “theory of bureaucratic collectivism.” Some fifteen years earlier, Shachtman had broken with the mainstream Trotskyist movement’s perspective that the Soviet Union was “a degenerated workers’ state” or “a worker’s state with bureaucratic distortions.” He insisted instead that Joseph Stalin had created “a bureaucratic collectivist evil empire” (the latter phrase is from Harrington’s book Socialism, published in 1970) that had to be opposed at all political costs. Shachtman and the ISL/YSL saw World War II as “a struggle between different warring empires” and insisted that “Marxists should support none of them” (28).

In the case of the Shachtmanite movement that Harrington joined in 1954, this “third camp” position had also come to mean moving away from revolutionary Marxism (34) altogether rather than advancing its original vision. As Greene demonstrates, many of the basic tenets of Harrington’s “democratic socialism”—especially the priority given to Democratic Party “Realignment”—had their roots in Shachtman’s move to the right.

In the 1950s, with the U.S. Communist Party in disarray and the SPA shrinking in size and influence, regroupment was inevitably on the agenda. The Socialist Party, reduced to under 700 dues-paying members and threatened with losing its formal affiliation to the Socialist International, decided to merge with the tiny Social Democratic Federation to form the Socialist Party of America-Social Democratic Federation (SPA-SDF). At the same time, Shachtman pronounced the ISL/YSL vanguard project no longer viable and argued “that the American left needed a Debsian style broad-tent social-democratic party that would be untainted by communism.” (43) In 1958, when the ISL dissolved itself, its members were able to take over the new but aimless SPA-SDF and fashion it into a revived Socialist Party. Harrington, although now approaching thirty, became leader of the SPA’s reconstituted youth wing (YPSL). He spoke widely on college campuses in the hope of recruiting students to the new version of the Socialist Party.

In the 1960s realignment became the central focus of Harrington’s political work. In the first issue of a biweekly paper he edited called New America, Harrington offered the following definition of “realignment”:

“American socialism must concentrate its efforts on the battle for political realignment, for the creation of a real second party that will unite labor, liberals, Negros, and provide them with an instrument for principled debate and effective action. Such a party as the Democratic Party will be when the Southern racists and certain corruptive elements have been forced out of it.” (52–53)

In the speeches I heard Harrington give in the late 1970s and 1980s, his main way of invoking—and defending—this vision of realigning the Democrats was to refer to “the left wing of the possible,” or sometimes to “the left wing of reality.” The “democratic left,” according to Harrington, works within the Democratic Party not “to maintain that institution but to transform it.’” (56; quoted from Towards a Democratic Left, 1968, 294).

Greene shows persuasively that Harrington’s vision of realigning the Democrats along these lines, “[f]or all its theoretical sophistication,” mistakenly assumed that the Democratic Party was “a loose coalition of diverse interest groups” that could be “captured” by socialists, rather than “a capitalist-controlled party” of the ruling class that cultivated the support of the working class and minorities but ultimately subordinated the real interests of these groups to its own agenda. (57–58)

Harrington’s orientation towards the Democratic Party was reinforced by the reception of The Other America in the years following its publication in 1962. The Kennedy administration was already planning an anti-poverty campaign, and when an anti-poverty task-force was created in early 1963, Harrington’s book was central to its thinking. This continued to be the case when Johnson assumed the presidency following Kennedy’s assassination on November 22, 1963. Johnson’s “War on Poverty” was formally launched in the State of the Union Address in February 1964 ahead of his landslide win over the reactionary Barry Goldwater. Sargent Shriver, Director of the Peace Corps, was asked to form a new taskforce and invited Harrington to be part of it. Harrington accepted. He insisted that Johnson’s version of the welfare state was “a necessary stepping stone on the road to socialism” (70).

With the intensification of campus-based activism led by Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) in the early 1960s, Harrington saw a vital new left arena in which the YPSL could intervene. He participated actively in the 1962 SDS conference at Port Huron, Michigan, under the banner of its forerunner, the Student League for Industrial Democracy (SLID), and made the case that student activists needed to see the civil rights and labor movements as crucial allies. The Port Huron Statement issued by the conference rejected “the kind of virulent anticommunism favored by Harrington” (81), but in other respects it reflected the interventions of Harrington and his fellow SLID members

When it came to the civil rights movement, some on the left saw the emergence of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) in the months leading up to the 1964 Democratic Convention as an affirmation of Harrington’s realignment strategy. But the Democrats refused to seat the MFDP’s primarily Black alternative slate of delegates and instead offered a demeaning compromise, which Harrington accepted on the grounds of “political practicality.” So much for realigning the Democratic Party.

In the months following Johnson’s election in 1964 the growing U.S. military intervention in Vietnam fueled a serious antiwar movement. Prior to the election, Harrington argued that though Johnson was heading towards war in Vietnam, he was a significantly lesser evil than Barry Goldwater, who was likely to lead the country into World War III. From his work with Shachtman and the ISL/YSL, Harrington inherited an increasingly critical attitude toward Ho Chi Minh and the Vietminh because of their perceived Stalinism. When SDS and other antiwar groups called for a march in Washington DC on April 21, 1965, Harrington criticized “SDS’s willingness to work with communists and Trotskyists” and argued that such involvement would “alienate liberals and moderates.” (94) The march turned out to be the biggest antiwar protest to that point in US history: instead of the 3,000 participants SDS predicted, 25,000 took part. For SDS and other antiwar radicals, Greene observes, “democratic socialists like Michael Harrington were no longer seen as allies but were part of the Establishment [that SDS was] fighting against.” (100)

On March 31, 1968, largely because of the growing momentum of the antiwar movement, Johnson surprised everyone by announcing that he would not run again for president. Harrington was quick to back the new frontrunner, antiwar Congressman Eugene McCarthy of Minnesota. But when Robert Kennedy entered the race, Harrington switched his support. Speaking at a campaign stop with United Farmworkers leader Cesar Chavez and SNCC leader John Lewis, Harrington saw “a socialist [himself] together with organized labor and a civil rights activist” as “the realization of Realignment” (102). When Kennedy was assassinated following his June 5 primary victory in California, Harrington’s hopes “lay in ruins” (102). His subsequent support for the eventual Democratic candidate, Vice President Hubert Humphrey, was “straight lesser-evilism” (103; Greene’s quotation is from Harrington’s 1985 book Taking Sides: The Education of a Militant Mind, 149).

Harrington’s ascendancy represented a victory for the growing conservatism of Shachtman’s influence inside the Socialist Party. Greene calls his chapter on Harrington’s politics during the mid-1960s “The Tightrope,” and with good reason. Harrington shared Shachtman’s hatred for New Left radicalism, but he wouldn’t dismiss the movement in toto.” (109) He also came to see Shachtman’s support for the most conservative layer of the labor bureaucracy as a threat to the cause of realignment. Yet in the 1968 strike of New York teachers, when United Federation of Teachers president Al Shanker blamed “black antisemitism” for a spate of recent firings and turned a majority of Black New Yorkers against the union, Harrington organized support for Shanker. Though the UFT won almost all its demands, its victory strengthened the right, damaged the liberal-labor-Black alliance, and seriously threatened both Harrington’s and Shachtman’s increasingly divergent approaches to a strategy of realignment.

By 1969 “the hostility between Shachtman and Harrington in the Socialist Party was boiling over.” (112) It reached a peak during the 1972 election, when the SP’s faint support for George McGovern, whom the Shachtman faction accused of being soft on communism, was at odds with Harrington’s belief that “McGovern is the closest thing to a Socialist to run for President since Norman Thomas.” (116) Harrington resigned as co-chairman of the SP before the election, on October 22. The SP renamed itself the Social Democrats,USA in December, and the following June Harrington resigned from the party.

Even before his resignation, Greene says, Harrington “was laying the foundations for a new socialist organization.” (119) In February 1973, he headed a weekend conference at New York University called, “The Future of the Democratic Left.” A few months later he and five hundred of his associates met in New York to found the Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee (DSOC), with Harrington as chair.

With only 250 “solid” members and a tiny budget, DSOC faced an uphill battle. It grew modestly but steadily during the 1970s, created a youth wing in 1975, and by 1980 could claim around a thousand members. DSOC supported reforms and worked to move the Democrats to what it regarded as the left. But to an important degree DSOC remained isolated from the liberal and labor allies it worked hard to cultivate. In the run-up to the 1976 election Harrington ended up supporting Jimmy Carter. He later argued that the party’s platform that year “was probably the most liberal in the history of the Democratic party” (127; quoting The Long-Distance Runner: An Autobiography, 104). Harrington’s hopes were boosted when Carter won the election and the Democrats gained large majorities in both the House and the Senate. But then, in the wake of the severe recession of 1974–75, the Carter administration delivered not New Deal reforms “but cutbacks and austerity.” (130) Carter was nominated again in 1980 and lost catastrophically to Ronald Reagan.

Out of the frustrations of the Carter years came a plan by Harrington and other founding DSOC members to expand by joining forces with the New American Movement (NAM), created in 1971 by former SDS and New Left activists. In March 1982, the Democratic Socialists of America was founded. Harrington was elected chair, along with a national board dominated by former DSOC members such as Irving Howe, William Winpisinger (president of the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers), feminist author Barbara Ehrenreich, and Manning Marable (distinguished professor of African-American Studies at Columbia University). With some 6,000 members, DSA was “the largest democratic socialist organization in the United States since the Socialist Party in the 1930s” (137)—a significant but sobering reality.

Reagan’s attacks on the working class during his first term—especially his firing in 1981 of striking members of the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO)—showed that the AFL-CIO leadership was unwilling to mobilize a serious rank-and-file fightback. Harrington and DSA were aware of the problem but reluctant to go against their allies in the union bureaucracy. Similarly, when the Reagan administration began to provide support for right-wing death squads in El Salvador and Nicaragua and for Islamic fundamentalist fighters in Afghanistan, Harrington was verbally critical but insisted that he was being so “in the name of the national security of the United States” (140; quoting Harrington and Howe, “Voices from the Left,” New York Times, 17 June 1984).

My strongest memory of being a DSA member during the Reagan years was traveling by bus to Washington D.C. with other Rutgers DSA members on August 27, 1983 for the twentieth anniversary of the great 1963 March on Washington. More than 250,000 civil rights activists were on the mall that blistering day. The most vivid of the speakers was Jesse Jackson, who told those of us in the crowd, “Our day has come.”

In 1984 Jackson and his Rainbow Coalition mounted a presidential primary campaign that, as Greene puts it, “had all the hallmarks of [Harrington’s] Realignment with a social-democratic program and support from labor unions, blacks and progressives” (141). Jackson also spoke out against US intervention in Central America, met with Sandinista leader Daniel Ortega and Cuban president Fidel Castro, and broke with the Democrat’s persistent Zionism [by] supporting the formation of an independent Palestinian state.” Jackson’s primary run offered “everything that Michael Harrington expected from a Realignment campaign,” Greene argues. Yet Harrington “willfully ignored it”—despite Manning Marable’s support for Jackson. The eventual Democratic nominee, Walter Mondale, moved to the right in response to Reagan’s popularity instead of to the left as represented by the Jackson campaign. The result? Reagan carried every state except Mondale’s home state of Minnesota. Greene provides a trenchant overview: “Just a scant four years before, Michael Harrington had predicted that a Reagan victory would open the Democratic Party to the left. Now the opposite was occurring as the party swung to the right and ditched its commitment to New Deal liberalism” (143).

When Jackson ran again in the 1988 Democratic primaries he toned down what most Democrats regarded as his “extreme” positions. This earned him Harrington’s and DSA’s support. He even asked for Harrington’s advice in writing some of his speeches. But the nomination went to a more cautious, low-key white liberal, Governor Michael Dukakis of Massachusetts. Harrington was quick to support Dukakis. As a comment on this outcome Greene quotes Lance Selfa’s 2008 Haymarket book The Democrats: A Critical History: “Instead of DSA influencing the Democrats, the Democrats influenced DSA” (148).

Less than a year after the 1988 election, Michael Harrington died of cancer. Green’s “Conclusion: The Legacy” notes that by this time DSA had moved even further away from its previous realignment strategy: “If we once positioned ourselves as the left wing of the possible, there is now no ‘possible’ to be the left wing of” (DSA’s “Where We Stand,” www.dsausa.org/about/where.html, quoted in Selfa, 229 and 283 n.).

With discerning insight Greene follows developments in DSA from the break with Harrington’s vision of realignment in the 1990s through the debates around a “dirty break” from the Democrats during the period leading up to and through the 2020 election. Greene insists that “[a]ll the factions in DSA are formally committed to the democratic socialist road to power that Michael Harrington would have felt quite comfortable with.” This generalization overlooks DSA working groups organized around revolutionary perspectives that Harrington wouldn’t have tolerated, such as the Afro-Socialist Caucus. But Greene is convincing when he argues: “When it comes to an orientation to the Democratic Party and ‘democratic-socialist’ reformism, Michael Harrington’s politics remain the ‘common sense’ of DSA.” (159)

Greene’s book ends with an “Appendix: The Meaning of Democratic Marxism” that evaluates Harrington’s considerable body of theoretical writing on a “real” Karl Marx who was “the foe of every dogma, champion of human freedom and [a] democratic socialist” (165, quoting Harrington’s 1976 book The Twilight of Capitalism, 2). Harrington’s Marx, Greene demonstrates, “bears little relation to the actual one since [Marx’s] revolutionary vision is effaced and he is transformed into a mild-mannered reformer . . . strikingly similar to Michael Harrington himself.” (177)

Today the US left, reformist as well as revolutionary, is confronted with challenges greater even than those faced by Harrington and his contemporaries. A Failure of Vision helps us understand what it will take to contend with the rise of right-wing authoritarianism and the depressing acceptance of lesser-evilism, and to build a diverse, multiracial, defiant socialism from below that can contend with the ravages of global capitalism in all its forms. The fight for reforms needs socialists who take reforms seriously but also insist on looking beyond them to the real possibility of creating a society free of systemic oppression and exploitation.

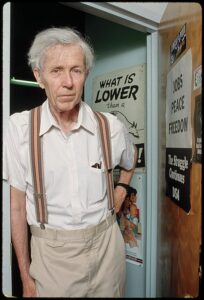

Featured Image Credit: Photo by Gretchen Dohart; modified by Tempest.

We want to hear what you think. Contact us at editors@tempestmag.org.

Bill Keach View All

Bill Keach is a member of the Tempest Collective, Boston Revolutionary Socialists, and Boston DSA.