When commonsense fails

Problems with Jacobin’s experimental study

“Common sense is a chaotic aggregate of disparate conceptions, and one can find there anything that one likes.” –Antonio Gramsci1

In November of 2021, Jacobin magazine announced the findings of their study, produced in conjunction with YouGov and the Center for Working-Class Politics2, “to survey working-class voting behavior in the United States.” Commonsense Solidarity: How a Working-Class Movement Can Be Built, and Maintained uses data collected through a targeted survey in order to form conclusions about working-class dispositions and political preferences. The report’s motivation is expressly for the purpose of electing Democrats who will need workers’ votes if they hope to win in the future. Commonsense Solidarity’s findings, released to the New York Times in advance of its summary and full release for Jacobin, aim to offer “new and powerful perspective on working-class political views.”

Authors Jared Abbott, Leanne Fan, Dustin Guastella, Galen Herz, Matthew Karp, Jason Leach, John Marvel, Katherine Rader, Faraz Riz, many affiliated with Jacobin, have produced a number of essays and journalistic pieces influential on the so-called “new socialist movement” around Democratic Socialists of America (DSA)3. They have now embarked on a new project to measure the attitudes of working-class people and determine ‘what works to get progressives elected?’

Conceptually, this is a good development. Socialists can’t rely on gut feelings and purely subjective assessments in understanding the world and ultimately changing it. In this regard, Commonsense Solidarity represents a welcome attempt to give objective consideration to politics, to attitudes among our class, and to the search for openings that can build and prepare workers for the conquest of political power.

And yet something is very wrong about Commonsense Solidarity. In design, construction, execution, and conclusion, the report is flawed if not willfully misleading. In what follows, we will explain Commonsense Solidarity as it has been presented, investigate its methodology, test its claims, and consider the piece politically. While initially we expected the report to be full of confirmation bias, close examination of their method presents a different sort of problem: whether their conclusions are supported by their own data.

What’s in the Report?

The report begins with a motivation: Democrats need the working class to win elections. The wave of “progressive Democrats” (such as Bernie Sanders, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Rashida Tlaib, and others) has largely been confined to urban centers, which the authors contend “have been concentrated in well-educated, relatively high-income, and heavily Democratic districts.” They then set out to find answers to some problems they pose: how can Democrats win over “the working class”; can “progressives” win outside urban liberal areas; and if so, how?

From there, they explain that they have engaged in an “experimental study, the first of its kind” in order to quantify the preferences of working-class voters in “five key swing states.” The study “nonrandom[ly]” selected 2000 participants (400 each) in Nevada, Michigan, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and North Carolina (19). “To ensure we only surveyed working-class individuals” the study selected respondents who were 1) not college educated; and 2) not self-identified Republicans.

The experiment itself “test[ed] how working-class voters respond to head-to-head electoral matchups.” Essentially, they created fictional politicians based on archetypes they devised, paired them against each other, and asked survey participants which they preferred and then to score them. These hypothetical politicians are differentiated by a number of variables: race, gender, policy positions, political affiliation, message delivery (“soundbites” or fictional statements delivered by these imagined candidates), and occupation.

With the data collected, the report plotted values in pages of busy visuals and concluded that they represent the entire working class. The graphs are effective for the purpose of dazzling the viewer and lending a sense of authority to the authors’ claims, but they are not particularly useful for conveying information or supporting their claims. All the same, the report declares that its method yields key takeaways about how Democrats can appeal to working-class voters:

- Focus on bread-and-butter economic issues

- Populist, “class-based” messaging works as well as standard Democratic messaging

- Anti-racism is fine, but don’t be “woke”

- Candidates should be Democrats, not independents

The remainder of the report expands on these conclusions and elaborates their methodology.

Concepts

When you turn to data to answer political questions, the way you design that investigation matters. Specifically, how you select a sample and define core concepts determines whether you will receive valid, generalizable answers. Commonsense Solidarity draws its nonrandom sample from a constrained universe of only five U.S. states and centers on three key concepts: social class, political affiliation, and political messaging. These are deployed inaccurately, inconsistently and in ways that appear to anticipate hoped-for conclusions.

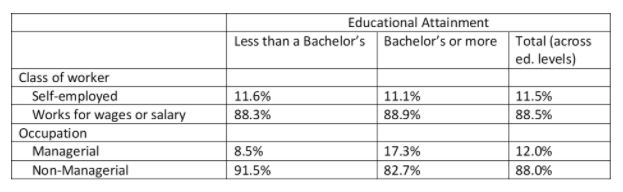

Social class is operationalized by the authors using educational attainment – “the preferred shorthand” of media pundits – and “working class” as all adults who don’t hold a bachelor’s degree (52). Respondents were selected only from this group. The authors acknowledge “the many limitations of this definition” and later deploy a “range of alternative measures” but this does not solve the problem: education doesn’t measure class because it doesn’t identify (re)productive relationships (4). These include whether or not one owns property, purchases others’ or sells their own labor power (or has it extorted), takes or gives orders at work, and so forth. College degrees may suggest those more likely to be managers, own a company, or be self-employed, but having one does not guarantee or define membership in these groups, as table 1 shows (below).

Applying the census indicators “class of worker” and “occupation” to nationwide workforce data, we see that large shares of non-BA holders are outside the most general definition of the working class—non-managerial wage employees—while the vast majority of BA holders remain within it. Educational attainment thus does not give a clear-cut picture of social classes; it instead yields vague descriptive strata that straddle class divides. All of Commonsense Solidarity’s “key takeaways,” however, are about the views or behavior of “working-class voters” – claims which don’t hold up when derived from a mixed-class sample, such as theirs (5-6).

What makes this even stranger is that Commonsense Solidarity deploys a different class identifier when constructing hypothetical candidates. These non-existent persons are defined by their occupation: “Teacher,” “Construction Worker,” “Small Business Owner,” “CEO of Fortune 500 Company,” and so on. Based on subjects’ responses to these hypothetical candidates, the authors draw the conclusion that “[w]orking-class voters prefer working-class candidates,” (5). This claim is meaningless, however, because different notions of class are used for subjects and candidates. Its general thrust seems plausible, but the conceptual confusion of their data does not support it.

The authors attempt to remedy the shortcomings of education-as-class with “different definitions” later on: “manual vs. mental work,” levels of “supervision at work,” “routine vs. creative work,” “class self-identification” and a “three-dimensional variable for class” derived from the first three and split into “middle” and “lower” class subgroups (51, 54, 59, 61, 57, 63). While it is certainly admirable to explore these dimensions, all are applied within the same sample defined by the authors’ original (and problematic) notion of class. These are not, therefore, different definitions of the working class but rather additional subcategories within the same educationally-defined stratum.

Political identity and political messaging are also problematic. The authors of Commonsense Solidarity “restrict [their] sample to individuals who do not identify as Republicans.” This is despite their stated interest in “working-class voters,” a sizable share of whom identify as Republican and discordant with noted vote switching across recent presidential elections (19).

On the candidate side, Commonsense Solidarity constrains things differently. Republicans and “generic Republican messaging” are included but independents off the Democratic ballot are not (10). Given that a historically high share of U.S. adults say a third party is needed, that many eligible voters don’t vote, and that independent or third-party candidates, including Bernie Sanders in all of his non-presidential contests, have either won or significantly impacted general elections, this is a questionable assumption. These choices make for an oddly synthetic landscape: no Republicans among subjects and no independents among candidates. This does not yield a “more realistic portrait of voter attitudes,” as the authors claim (5).

And political messaging––how the study’s candidates “speak” to issues––is defined by a specious dichotomy between “wokeness” and economic populism. Study subjects were shown pairs of hypothetical candidates that varied on seven dimensions, one of which was “messaging style.” “Each communication style is delivered in the form of a hypothetical soundbite,” the authors tell us, which “draw[s] on language and themes from actual political messaging…and reflect the most important general strands of contemporary campaign rhetoric” (10). They condense these into a five-point scale ranging from “progressive populist” through “‘woke’ progressive,” “‘woke’ moderate” and “mainstream moderate” to “Republican” (10).

“Wokeness” is a key differentiator here, but it is not a politically precise term. Broadly meaning “alert[ness] to racial prejudice and discrimination” and popularized by Black Lives Matter struggles, it is wholly compatible with economic, social, and political egalitarianism. At the hands of Commonsense Solidarity authors, however, it is sectioned off as some contrary viewpoint. The alleged trade-off between economic “populism” and anti-racist “wokeness” then becomes a central theme—indeed a core finding—of their inquiry:

Progressives do not need to surrender questions of social justice to win working-class voters, but “woke,” activist-inspired rhetoric is a liability. (5)

Blue-collar workers are especially sensitive to candidate messaging — and respond even more acutely to the differences between populist and “woke” language. (6)

We should be skeptical. Jacobin editors and affiliated authors have clearly staked out a position, developed long before this study, against the centrality of antiracism to left coalition-building. That Jacobin now sponsors a study in which “wokeness” is manipulated into a narrow alternative to economic populism raises red flags—and indeed “take[s] the bait” of conservatives that one Jacobin author once warned against. Why should awareness of racial injustice be counterposed to redistributive economics when a very large share of those voicing the first also voice the second, and when the study’s truncated “woke” soundbites belie the actual statements of their real-life inspirations?4

This kind of misrepresentation casts a shadow over the study’s design and the authors’ interpretation of what subjects’ choices mean – redistribution over racial justice, as if the two were exclusive.

Analysis

Let us pretend for a moment that Commonsense Solidarity’s muddled notions of class, party, and messaging are unimportant. Would its conclusions hold up? Does the study have what researchers call “internal validity” – plausible support for its claims in its findings? Our deeper dive reveals that it does not.

The report makes use of a quasi-experimental technique known as conjoint analysis. Without getting too technical, what this effectively does is allow for simultaneous and differentiated assessment of the factors driving individual choice. These could be almost anything: brands of cereal, immigration policies, or political candidates, just to name a few. Overall, Commonsense Solidarity makes appropriate use of conjoint analysis and its authors even heed warnings to use “marginal means” rather than “average marginal component effects” when reporting their results.

Yet they fail to heed their own advice and a basic rule of statistical reasoning. In walking readers through that labyrinth, the authors state:

The bars around each dot indicate how confident we are that a given value is correct. Each bar to the left and right of the dot indicates the margin of error for a given estimate…It is important to note that if the bars overlap with the vertical line at .5, we cannot conclude that respondents had a net positive or a net negative opinion of that characteristic (since there is no significant difference between the value of the dot and .5).

Similarly, if the bars around one dot overlap with the bars around another dot, we cannot conclude that there is any statistical difference between the two characteristics. (23, emphasis added)

More straightforwardly, overlapping bars for two or more elements means there is no difference between them. It cannot be inferred that one exists, especially not among all “working-class voters” as the authors mistakenly do.

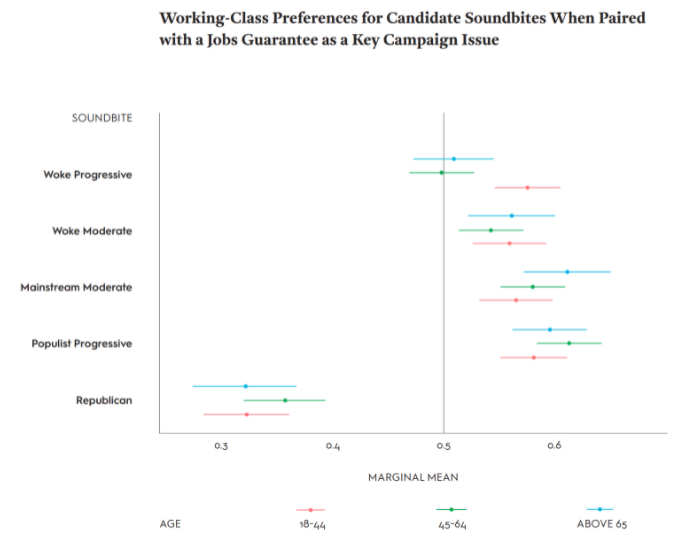

On page 27 they state, “younger respondents did tend to prefer progressive soundbites over their moderate counterparts.” This is in reference to their chart below (Figure 1). Four of the five red bars––the margins of error for “younger respondents” (ages 18-44) on all but the Republican soundbite––overlap heavily. On three of the five messaging styles (“woke moderate,” “mainstream moderate” and “populist progressive”) the error bars for all three age groups also overlap within and across soundbites. This means there is no statistical difference between them and thus no support for the authors’ statement that younger respondents “prefer” any of the non-Republican styles over any other.

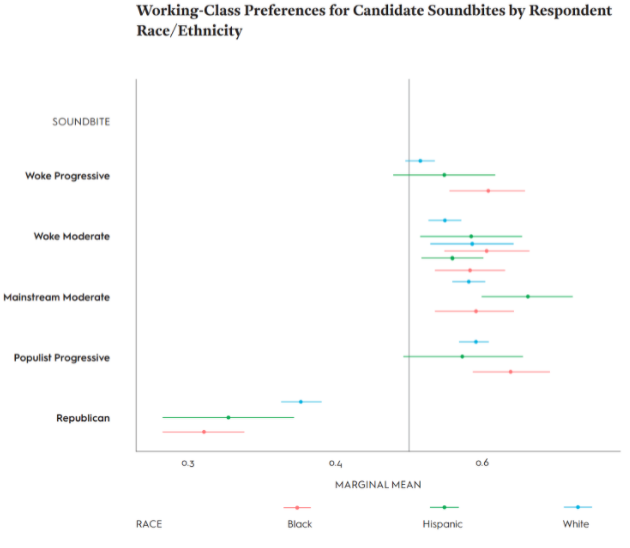

The same issue arises in the following breakdown of racial groups. There the authors state:

White respondents narrowly preferred the progressive populist soundbite over the mainstream moderate…black respondents narrowly preferred the progressive populist messaging over the woke progressive…and Latino respondents preferred the mainstream moderate rhetoric…But these differences were all relatively small. (27)

In fact, they were non-existent. All error bars for these rhetorical “preferences” overlap, which means they aren’t preferences or aversions. Statistically speaking, white respondents preferred “woke moderate,” “mainstream moderate” and “populist progressive” messaging equally over their “woke progressive” and Republican counterparts. Black respondents preferred all non-Republican messaging styles equally to that one, and the same goes for Latinx respondents. Again, we have an unsupported leap from statistical sameness to narrative difference.

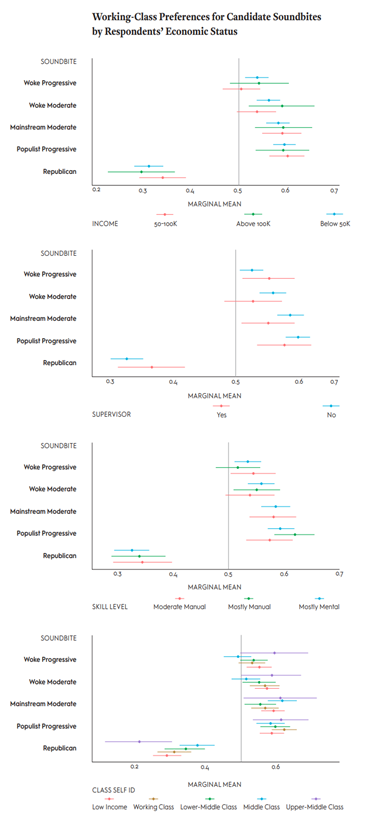

In comparing the attitudes of class-like subgroups toward these same five messaging styles, the authors repeat their error. “Populist rhetoric,” they claim, “proved particularly strong compared to other types of campaign messaging among respondents who make less money, are not supervisors, perform manual labor, and who self-identify as working-class” (30). “Our results,” they conclude, “show that these working-class subgroups preferred a class-based appeal with considerably more enthusiasm than other respondents” (30). Yet even a cursory review of these results shows heavy error-bar overlap––that is, non-difference––among these subgroups (Figure 3). Respondents from all three income groups and “skill levels” equally preferred “woke moderate,” “mainstream moderate,” and “populist progressive” messaging styles. So did those who self-identified as “low income,” “working class,” “lower-middle class,” and “upper-middle class.” And both supervisors and non-supervisors preferred “mainstream moderate” and “populist progressive” styles equally. Put plainly, this evidence does not support the authors’ claims.

Ultimately, this amounts to an argumentative fallacy: inferring from non-significant differences that subjects or subgroups differ. The authors know this and advise their readers accordingly. Yet they offer such claims repeatedly throughout their 53-page results section, never limiting their import to the study’s five-state sampling universe but rather generalizing to the entire U.S. working class. Such claims should be discarded, as well as most of the report’s summary “takeaways.”

Politics

Commonsense Solidarity presents itself as revealing important information about how to win working-class votes for a progressive, Democratic electoral project. It has two audiences: Democratic Party operatives, to whom they appeal to shift their electoral strategy; and a broad left, who they wish to win to their conclusions about remaining in the Democratic Party, using “economic populist” messaging and avoiding “wokeness.” Even among skeptics who may disagree with the particulars, Commonsense Solidarity’s status as a report, relying on data, visualizations, and experimental methodology, make it more persuasive than an essay would likely be.

The issue is that when you look under the hood, it’s a lemon. For a report that attempts to extrapolate the preferences of the entire U.S. working class, Commonsense Solidarity is unconvincing on its own terms. It uses a transparently non-representative sample that excludes most of the class based on geography, as well as large sections of it based on education and political affiliation (identifying as Republican); it deploys biased or simply faulty indicators of class, political messaging, and political affiliation; and it inserts findings of difference where none statistically exist. The authors end up not being able to say much of anything, yet they still present their study as if it backs up claims that several of them have argued for years. The conclusions are what appear to matter here, and the authors fudge the numbers in service of a particular project: “national political realignment on progressive terms” (3), or in other words, Democratic Party realignment.

From top to bottom, Commonsense Solidarity uses flawed reasoning. For one, it presents political affiliation as essentially fixed: Republicans will simply always be Republicans, and there’s no use including them when considering how to attract working-class votes (10, sub 14). This assumes both that political identity is immutable, and that working-class Republicans are not expressing any sectional class interest in aligning with the other party of capital. Like most liberal progressives, the Commonsense Solidarity authors assume that Democrats are the natural home for workers and make this clear in refusing to offer independents as hypothetical candidates. The takeaway is to compete for a limited pool of voters who may be inclined to vote Democrat. In that way, they remain limited to a Gramscian “common sense” and never plot a course to “good sense.”

Beyond that, they perceive voter behavior simply as a product of individual preference. This is standard rational-choice liberalism: suggesting voters weigh desires then express them by endorsing the most fitting candidates on the ballot box. Commonsense Solidarity tries to see what those preferences are (allegedly economic populism) and then sets out to prove that if working-class voters were given the opportunity, they would simply pursue them. But voter behavior in bourgeois democracies is not a straightforward result of personal preferences. Money, power, manufactured consent, and political calculations play significant roles in determining who people vote for. Famously, voters in South Carolina, who overwhelmingly favored Medicare for All, voted not for Bernie Sanders, the policy’s main proponent, but for Joe Biden. The fantasy game that Commonsense Solidarity plays is hoping to pair the structural power of the Democratic Party with the favored candidates of DSA thought leaders and getting “the Left” behind it.

There are more realistic left alternatives. They involve casting aside the Democratic Party and formal elections as primary sites of struggle in favor of social movements and independent organizing. Equally large practical questions hang over them as they do over Commonsense Solidarity’s realignment strategy. And they share a fundamental one: “how a working-class coalition can be built.” We should investigate these questions thoroughly, both as researchers and as activists, using all relevant tools. But we should do so accurately, without leaping toward answers the data doesn’t provide. This cannot be said for Jacobin’s initial foray into empirical research.

Categories

We want to hear what you think. Contact us at editors@tempestmag.org. And if you've enjoyed what you've read, please consider donating to support our work:

DonatePete Ikeler, Andy Sernatinger, & Erin Cass View All

Peter Ikeler teaches sociology at SUNY Old Westbury. He is the author of Hard Sell: Work and Resistance in Retail Chains (Cornell University Press, 2016) and a member of the Tempest Collective.

Andy Sernatinger is an activist in Madison, Wisconsin, and member of the Tempest Collective. He writes frequently on developments in the Democratic Socialists of America and the labor movement. His articles have appeared in New Politics, In These Times, and Tempest.

Erin Cass is a queer Romani data scientist and activist based in the Adirondack Mountains of upstate New York. They are a member of the Tempest Collective.