A new face for old politics

Eric Adams and the return of law & order

Since taking office as mayor of New York City, Eric Adams has naturally stepped into the headlines. His actions have already garnered some negative attention, including his attempt to hire his brother to a highly paid position, a past federal corruption controversy surrounding his newly appointed Public Safety Chief, and the disparaging comments he made about ‘low-skill’ workers. The majority of the coverage, however, has been dedicated to Adams’ clear priority since taking office; cracking down on crime and gun violence.

Adams and the media have focused so intensely on crime and violence that President Biden visited New York in early February to discuss the issues and offer federal support for Adams’ crackdown.

A tough-on-crime, law and order approach is certainly nothing new for a Democrat. In this sense, Adams’ politics are quite similar to Democrats who came before him, like Bill Clinton, Joe Biden—especially during his time as a Senator—, Kamala Harris, and former New York City Mayor Ed Koch. These Democrats all espoused—and some continue to espouse—politics that mix elements of tough-on-crime, law and order approaches, with a pro-business agenda. As always, promises which never come to fruition are made to the working class.

Importantly, the main differences between the politics of Adams’ and the above-mentioned Democrats, on the one hand, and former New York City Mayors Rudolph Giuliani (Republican) and Michael Bloomberg (Republican and later Independent), on the other, are superficial. The base to which they appeal and their rhetoric may differ, but beneath the surface, their politics are overwhelmingly similar.

Before examining what makes Adams different from these other politicians, we first have to acknowledge the larger context in which Adams became mayor. Unlike the early 1990 and early 2000s when Clinton and Bloomberg, respectively, came to power, Adams did so in the era of Black Lives Matter. He won office during a time in which slogans and movements to ‘defund the police’ have become mainstream, and the abolition of the police is something that exists in the public consciousness, if not yet supported by the majority of people.

It is also a time in which the Democratic Party has a more progressive wing, both nationally and in New York City, than it has in a long time, and certainly more so than during the preceding decades.

Despite this context, and in the wake of one of the largest anti-racist uprisings in the country’s history, Adams, an African-American, tough on crime former cop, is now Mayor of New York City.

While all of the Democratic and Republican politicians named above espouse(d) anti-Black politics, it is Eric Adams who launched a “stop the sag” campaign while he was a State Senator, targeting Black men’s sagging pants, this is in line with his recent attacks on drill music. In the context of today’s political landscape, perhaps Adams is uniquely positioned to explicitly make these attacks, whereas many other politicians would avoid doing so.

The combination of Adams’ identity and politics present a specific and unique challenge to the Left. By examining his background and politics, the current economic, social, and political situation in the city, and what he has done since taking office, the aim of this article is to provide a general picture of what we’re up against for the next four years.

Eric Adams: Background and Police

Adams is only the second Black mayor in New York City’s history. He is also the first Mayor to come from a working-class background in a long time, growing up in predominantly Black, low-income neighborhoods in Brooklyn and Queens. In a city like New York, in which a significant portion of the population is Black and Brown, as well as working-class, Adams was able to resonate with voters from this shared experience; he did significantly better than his opponents in the Democratic primary with working-class voters of color in the outer boroughs.

When Adams was a teenager, he and his brother were the victims of police brutality. Two white cops were beating the two Black teens in a police precinct when a Black cop intervened. Adams notes that this intervention and what it represented to him—the perceived power and respect that the Black cop commanded—as well as the overwhelming power the police wielded in general, inspired him to become a cop.

This incident also foreshadows Adams’ relationship to and time in the NYPD. During his 20-plus year career, Adams was consistently outspoken and critical about the power dynamics and internal functioning of police departments. He earned a reputation as someone who was never afraid to speak truth to power.

Crucially, although perhaps unsurprisingly, Adams’ criticisms of the police rarely if ever focused on their role in society. His experiences never led him to wonder whether the very institution of the police was, in fact, the problem. Rather, while he occasionally criticized the excesses of police brutality, he primarily took aim at the racism and discrimination within police departments. He brought attention to, and fought against, the obstacles and challenges Black cops faced when it came to advancement within what has historically been a predominantly white and intensely racist institution.

In short, Adams took aim at the racism within police departments, but not the racism of the very institution itself.

Adams’ background presents unique challenges for the Left. He is deeply pro-police, but also has a history of being critical of them. He can also cite his experience as a cop to identify the places in which they need improvement, and how to make that happen. Ultimately, the aim of Adams’ criticisms towards the police is to strengthen and bolster the institution, rather than dismantle it.

Eric Adams: Campaign and Coalition

After working his way up to the position of captain, Adams retired from the police in 2006. He went on to serve as a State Senator from 2007-2013, before becoming Brooklyn Borough President, where he was able to further develop and hone his skills as a politician in the city’s Democratic Party Machine. He served as Borough President from 2013 to 2021.

He emerged victorious out of a Democratic mayoral primary which lacked much of a Left presence at all, although he was arguably the most conservative candidate of the group. The ‘progressive’ Left in New York City was primarily split between three candidates: Scott Stringer, Maya Wiley, and Dianne Morales. None of these candidates are socialists; in fact, it would be difficult to even categorize them as social-democrats. Stringer is a friend of the real estate industry, Morales supports charter schools, and Wiley was De Blasio’s appointed successor. The campaigns of both Stringer and Morales both imploded due to scandals, and Wiley finished in third-place behind Adams and Garcia. The Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) opted not to endorse any of the candidates, and, in the absence of any Left alternative, Adams received 31 percent of first-round votes, ten percent more than any other candidate.

His campaign centered on cracking down on crime while making New York City more business-friendly, which represented a stark rhetorical departure from the 2013 campaign of former Mayor Bill de Blasio, with its focus on inequality and invocation of the ‘tale of two cities.’

A phrase that Adams, on the other hand, often repeated was that ‘public safety is the prerequisite for prosperity.’ Public safety refers to both COVID-19 and crime, but the latter has been his primary focus.

During his campaign, Adams secured support from various sectors of big business and capital, including real estate and cryptocurrency, in addition to developing individual relationships with billionaires like Rupert Murdoch and Michael Bloomberg.

Adams’ relationship to real estate took center stage following a devastating fire in the Bronx that left 17 people dead, after it was revealed that a member of Adams’ housing transition team, Rick Gropper, is a co-founder of one of the firms that purchased the building in 2019. Gropper’s company, Camber Property Group, has been rapidly expanding recently, buying up residential buildings throughout the city and especially in the Bronx. The company now owns 5,800 residential units. The fact that Adams would select someone like Gropper for his housing transition team is not surprising, but it is certainly informative.

“New York will no longer be anti-business,” said Adams, distancing himself from de Blasio, and adding that he would not allow New York City to “turn into the dysfunctional city that we have been for so many years.” Adams sought to make it clear that his administration was not going to be a continuation of de Blasio’s failed attempts at social democracy; he was charting a decidedly different, pro-business course, and wanted everyone to know.

Some of the city’s largest unions threw their support behind Adams in the primary, with most of the remaining unions falling into line for the general election. On one hand, we shouldn’t read too much into organized labor’s support for Adams—large business unions, especially in New York City, will always back a Democratic candidate. This support doesn’t tell us anything about Adams’ plans for organized labor.

On the other hand, Adams was able to somewhat effectively paint himself as a pro-labor candidate. Not only did he come from a working-class background, but he also was a ‘union’ member himself during his time with the police.

“I am you,” said Adams to a crowd of District Council 37, AFSCME members, the city’s largest public-sector union, during a speech after the union announced its support for him.

Adams contradictory views and rhetoric—pro-police and pro-justice; pro-business and pro-labor; an ally of big real estate and a supporter of affordable housing;—explains the headline of a New York Times that reads “What Kind of Mayor Might Eric Adams Be? No one Seems to Know.”

While the New York Times might not have known what kind of Mayor Adams was going to be, the writing has always been on the wall.

The Economic Situation in NYC

Before looking at what Adams has done so far in office, it is worth first taking a step back and looking at the current social and economic situation in New York City, as this context will largely shape and inform Adams’ tenure as Mayor.

Almost two years into the COVID-19 pandemic, the economic situation in New York City remains fairly grim. Hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers are unemployed, underemployed, and/or facing eviction. The city’s unemployment rate is around 9.4 percent, which is more than double the national average. New York City lost 960,000 jobs when the pandemic hit, less than half of which have been restored, and, according to recent projections, the city will not regain all the jobs it lost until late 2025.

This dire situation, however, predates the pandemic. Income inequality in the city has been worsening over the last decade, with people of color bearing the brunt of the widening gap between the rich and the poor. With the acceleration of these trends resulting from the pandemic, we may soon reach pre-recession (2007-2008) levels of inequality once again.

Federal funding, plus $1.6bn more in tax revenue than was expected, have prevented a catastrophic situation, but many remain on the brink of collapse with no lifelines on the horizon.

It is uncertain, however, what federal funding will look like moving forward, and according to some sources, New York City is facing budget deficits of $3.6bn for 2023, $3.5bn for 2024, and $2.9bn for 2025. Budgets deficits do not necessarily imply or necessitate cuts and austerity, but they often provide politicians with the pretext to implement such policies. Thus far, all indications point towards this being Adams’ plan.

Despite the economic situation described above, Adams’ rhetoric regarding the economy has tended to focus more on inefficiency and a bloated public sector rather than inequality and the desperate position hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers are currently in.

Before assuming office, Adams called for a two-year hiring freeze and spending cuts of three percent for every city agency. He followed through with these calls in his first proposed budget, officially proposing the cuts, as well as reducing the city workforce by 10,000 workers through “attrition and unfilled vacancies.”

Agencies specifically facing COVID-related challenges will be exempt from making such cuts. Adams has included the Department of Corrections on this list, as well as the NYPD, citing the ongoing wave of violent crime as the reason.

Moving forward, Adams will have to make important decisions that impact public spending, such as contract negotiations with city unions. The first of these large negotiations will likely be with DC37, whose contract expired last May. How Adams negotiates with DC37 will be worth monitoring, as it will give us insight as to how he may approach negotiations with subsequent public unions. He will also have to make decisions for programs such as universal pre-k for which federal funding will be running out.

Adams has made it clear that austerity is coming. In addition to the cuts and freezes he has already called for, he is rolling out the same old business jargon, promising to ‘streamline’ the city’s ‘inefficient agencies,’ with help from a newly created position titled ‘efficiency czar.’

“New York is a corporation,” said Adams; “I’m the CEO of New York City. I’m going to put my systems in place.”

NYC: A ‘Sea of Crime?’

In addition to the economy and the budget, crime is the other main issue defining the city at the moment.

Politicians like Adams, with the eager help of the media, have created a frenzy around the issue of violent crime. Guns, shootings, and murders dominate media coverage and Adams’ rhetoric. The more alarming the crisis appears, the more of a mandate Adams will have to deal with it in the way he sees fit and deems necessary.

On February 3, Adams appeared with President Joe Biden at NYPD HQ, and went as far as to suggest that “we could have a 9/11 response to this violence. We came together as a country when international terrorists decided to change our way of life. And we responded.” Drawing a parallel between the current situation and 9/11 is truly absurd, but it demonstrates the lengths to which Adams is willing to go to paint the current crisis as almost existential. =

It is true that serious crimes increased in 2021, and that murders have been on the rise since 2018. Hate crimes also rose 93 percent in 2021, pointing to the increasingly xenophobic and nativist climate present in this city and country today. The recent uptick in violent crime and murder, however, represents only a small part of a much larger story.

There were fewer murders in New York City in 2021 than in any year from 1962 to 2009. While some in the media are wondering aloud if we are headed for a return to the crime and violence of the 1970s and 1980s, these parallels are entirely off base when we look at murder statistics. In 1970, 1980, and 1990 the murder rates were respectively 2.2, 3.7, and 4.6 times higher than they were in 2021. There is simply no comparison.

Despite these facts, 72 percent of respondents in a May 2021 poll agreed that there should be more police officers on the streets. While the framing of the question was deeply flawed, the results do show us that people are highly worried about crime, and that they want more, not fewer, police to deal with it. The campaign to whip up fear around violence and crime is clearly making an impact on people.

A similar pattern emerges when we look at crime and the subways. Serious crimes in New York City subways are the lowest they’ve been in decades. Despite this, a recent survey shows that 90 percent of New Yorkers who have stopped riding the subways during the pandemic said that issues such as ‘personal security’ and ‘harassment’ would factor into their return. Adams proposes more police on the subways with little to no discussion or examination of the dilapidated state of public transit or how we got here.

Beyond painting the city and its subways as overwhelmed by violent crime and shootings, Adams and the media have also cynically taken advantage of certain high-profile tragedies, as well as the shooting of five police officers (two of which were fatal) since he took office.

None of this means that the issue of violence, and the low-income communities this violence predominantly impacts, are not serious issues; rather, it seeks to demonstrate that the issue of violence is being blown out of proportion and framed so as to justify a brutal, repressive crackdown on the cities most marginalized communities under the guise of social justice. Adams’ pro-business and pro-police approach will undoubtedly fail to provide any solutions to the causes underlying these issues, and will instead inflict further harm and damage onto communities that are already suffering.

Eric Adams and Public Safety: Pro-Police, Pro-Prison, but what about Schools and COVID-19?

In order to address the current ‘crisis,’ Adams has pledged to increase police presence in the subways (“omnipresence is key”), and bring back plainclothes police units. This represents a blow to the gains made by the Black Lives Matter movement, which included forcing the previous administration to get rid of the anti-crime plainclothes police units in the first place.

Both of these decisions will undoubtedly lead to the police killing more innocent people, who will predominantly be working-class people of color, in addition to an increase in general violence, abuse, harassment, and surveillance of those same communities.

Adams recently rolled out his ‘Blueprint to End Gun Violence,’ which ultimately serves as a “series of attacks, disguised as proposed amendments, on bail, discovery, and juvenile justice reforms [fought for by advocates] enacted recently in the city,” devoid of any real solutions to the current violence in the city. Unsurprisingly, Pat Lynch, the president of the Police Benevolent Association of the City of New York, released a statement praising Adams’ plan and his advocacy of the police.

It will be interesting and important to monitor how Adams’ relationship with the NYPD and police ‘unions’ continues to develop; as discussed above, while a former cop and law and order advocate, he will not bend to whatever the police want. Furthermore, he will have to deal with public pressure and scrutiny after the next inevitable high-profile police brutality incident.

This may provide for some friction moving forward, given that the police are virulently against any form of accountability and are willing to go to war against mayors who stand up to them in any capacity. Adams’ conception of public safety relies heavily on the police and prisons. In the context of the current ‘crisis,’ bail reform is increasingly taking center stage as a primary problem. Adams’ solution to the problem is to incarcerate more people, who are younger, for a longer period of time. Even Governor Kathy Hochul is providing resistance to Adams’ attempts to undo bail reforms.

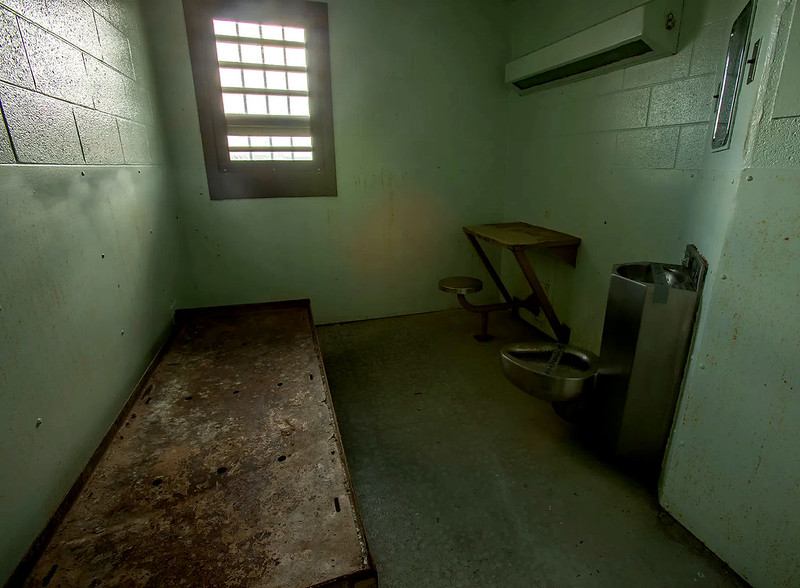

As it relates to prisons, the corrections’ officers union may be the group that has benefited the most since Adams’ became mayor. Adams’ has vowed to keep solitary confinement, an inhumane form of punishment, in city jails and bring it back to Rikers Island. This policy will only further worsen the humanitarian crisis in one of the worst jails in the country. A devastating 90 percent of the inmates at Rikers are Black or Brown, and 15 incarcerated people died there in 2021 alone. COBA, the correction officers’ union, supported the policy of bringing back solitary confinement at Rikers. But this is far from the only thing Adams’ has delivered to the union. After becoming mayor, Adams replaced the former Correction Commissioner, Vincent Schiraldi, who was preparing to battle the correction officer’s unions, with a new Commissioner who immediately proved to be a friend to the union.

Louis Molina, the new commissioner, asked Sarena Townsend to step down immediately shortly after he was appointed by Adams. Townsend, the Deputy Commissioner for Intelligence and Investigation, had been lauded by a federally court-appointed monitor for her investigations into over 8,800 incidents of excessive use of force against detainees. COBA celebrated her removal, and Molina, since taking over, has already eased the rules regarding calling out sick.

In addition to all of this, Adams also proposed an increase in spending for the Department of Correction’s in his proposed budget, from $800 million to $1.2bn. A 50 percent increase is drastic, especially when Adams’ is making cuts to most other agencies.

It is clear that for Adams, public safety is synonymous with cracking down on crime. This, in turn, necessitates a stronger, more visible police force, laws that give the police more leeway and the power to further and more intensely criminalize people, and an empowered carceral system and those who work in it.

What about COVID-19, though? Does public safety also apply to the pandemic? A quick look at Adams’ engagement with schools, COVID-19, and the teacher’s union gives us a glimpse into his contradictory conception of public safety, as well as, perhaps, what his relationship to non-cop unions may look like.

Adams’ mayorship began amidst a staggering surge brought on by the omicron variant in New York City. Attendance in schools plummeted, and while some public school districts around the country closed, Adams insisted that schools in New York City would stay open. He also took a shot at Lori Lightfoot, the Mayor of Chicago, saying “This is not Chicago…We can resolve this. We can get through these crises and we will find the right way to educate our children.” Adams wanted to make it clear that he would not allow the teachers union in New York City to play a role like that of their counterparts in Chicago.

Michael Mulgrew, president of the city teacher’s union, initially told members that “he had encouraged Mr. Adams to start the year remotely,” this has yet to materialize. Meanwhile, he has been working closely with Adams to ensure that schools can remain open.

With Adams and union leadership in sync (which doesn’t come as a surprise), it will be up to the rank-and-file, students, and communities to fight for the policies that keep them safe. High school students provided an example of what this could look like in mid-January, staging a walk-out in order to bring attention to the dangers posed by in-person learning. “Public safety needs to come first,” remarked one student, serving as a reminder to Adams that public safety encompasses more than just police and incarceration.

As a result of the protest, organizers met with NYC Chancellor David C. Banks, and although the meeting is unlikely to provide a direct improvement to the situation, student self-activity has clearly demonstrated what is necessary for those actually impacted by the quality of in-person learning as COVID-19 continues to rip through schools.

Adams, the Democrats, and the Left

“I am the face of the New Democratic Party,” said Adams shortly after it appeared he had won the Democratic primary.

In many ways, Adams’ politics are simply a continuation of Democratic Party politics. Adams’ statement, then, seems to be taking aim at the progressive wing of the party, led in part by DSA. For Adams, the enemy is not the right, it is the progressive wing of his own party. He is telling progressives and DSA that the Democratic party is not theirs, and on this point he is right. In November he said if elected, he was going to “start the process of regaining control of our cities…[from the] DSA socialists.”

Thirty-five of the fifty-one council members in the city council are new, and the council is perhaps more progressive than it has ever been. But while there seems to be a large gap between Adams’ politics and those more progressive council members, it remains unclear how much they will be willing to push back against him.

Many Democratic council members, while not necessarily the progressive members, have expressed support for his Blueprint to End Gun Violence and his crackdown on crime. Furthermore, more progressive members of both the city council and Congress have discussed finding common ground with Adams and the necessity of making compromises to get things done. While this language is textbook for politicians, it highlights the lack of a principled alternative to Adams.

In a recent significant development, Francisco Moya, who Adams strongly supported and pushed for to become speaker of the council, lost to Adrienne Adams (no relation to Eric Adams). Despite the fact that Adams’ “political capital is probably at its zenith right now,” he was still unable to pull the strings to get Moya elected speaker. Moreover, a coalition of powerful unions backed Adrienne Adams’s candidacy, in direct opposition to the aims of Eric Adams. This loss is significant for the mayor not only because of the outcome, but also because of the process; it was an early statement that he will not be able to get everything his way, especially not without push back.

Conclusion

Eric Adam’s victory, and the law and order platform upon which he ran, represented a sobering moment for the Left. New York City voted for a Black, tough on crime, former cop as its Mayor just a year and a half after the anti-racist uprisings of the summer of 2020.

This isn’t to say that Adams’ victory is the only, or best, weathervane for the current state of the Left, but his victory certainly does tell us something about its current state. Furthermore, and most importantly, his policies will inflict massive violence on working-class people of color throughout the city. His pro-police and carceral policies, coupled with his pro-business, efficiency-obsessed politics, on top of the austerity looming just around the corner, will undoubtedly only cause further harm for working people.

We have to keep in mind, however, that less than one million people voted in the Democratic Party’s mayoral primary, and only slightly over one million people voted in the general election. Adams’ politics do not necessarily represent what the majority of people want or believe; in lieu of a clear alternative, however, Adams was able to fill the empty space and push his reactionary politics as the only solution to the situation we find ourselves in today.

The urgent task currently facing the Left in New York City is to challenge Adams in every way in our power, making it as difficult as possible for him to implement his policies, while articulating and mobilizing around an alternative program. We look to be in for a long four years and we have no time to waste.

Featured Image Credit: Photo by Tony Fischer; modified by Tempest.

Categories

We want to hear what you think. Contact us at editors@tempestmag.org. And if you've enjoyed what you've read, please consider donating to support our work:

DonateBen Rosenfield View All

Ben Rosenfield is a member of the Tempest Collective living in Brooklyn, NY.