Defeating the legacy of Pinochet

From the Chilean October to Boric and beyond

Chile between rebellion and the institutions

In recent years, Chile has again been in the eyes of the international Left, and rightly so. In just over two years, the country—for decades seen as a safe “oasis” and a model by the elites and the right in Latin America and beyond—has experienced a rebellion. This was rebellion against that right-wing ideal, and against the legacy of the Pinochet dictatorship which had forcibly built such favorable conditions for capital, on the bones of tens of thousands of murdered, disappeared, and imprisoned.

This rebellion began in the streets, through insurgent mass movements, and has played out through an ongoing process of constitutional change and a presidential election, in which the two coalitions that had monopolized three decades of limited democracy, were relegated to fourth and fifth place. Finally, Gabriel Boric’s victory in the second round of voting on December 19, 2021, over the far-right candidate, Antonio Kast, and its significance for the political perspectives of Chile and the continent, have been a subject of analysis across the Left.

In this article we seek to contribute to these analyses while raising some matters of debate and preliminary hypotheses about the dynamics of the political situation in Chile, generally, and with Boric´s government specifically. In doing so, we will review the events of the last two years and their relationship to the structure and politics inherited from the Pinochet dictatorship. The “Chilean October” opened a new political stage in the country. Analyzing this process, and the role played by the different political forces in it, is crucial to thinking about the dynamics of what is to come.

The Chilean “oasis”

The so-called “Chilean model” was born from defeat. In the late 1960s and early 1970s the rise of struggles amongst the working class, the student movement, and the peasants represented a true revolutionary challenge to the bourgeois order. It pushed the reformist government of Salvador Allende to take increasingly radical measures, and in the face of its hesitations and concessions and the threat of reaction, workers formed organs of an embryonic dual power, the cordones industriales.

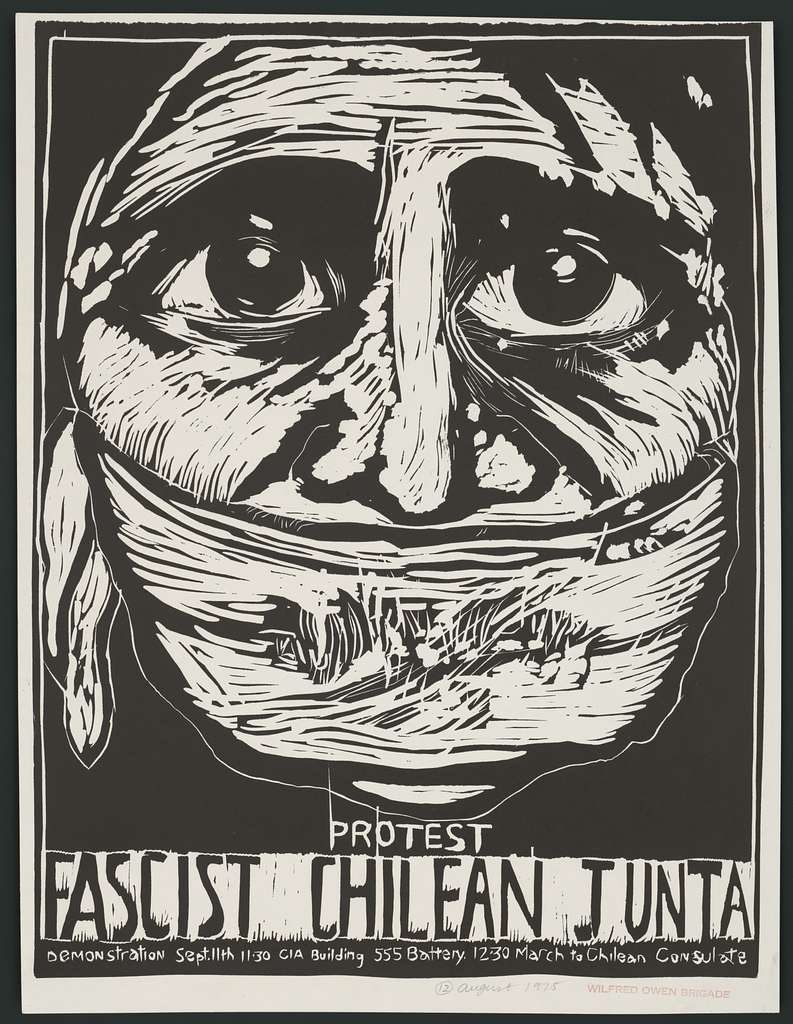

The Pinochet dictatorship unleashed a ferocious, violent repression aimed at disciplining the working class and the popular sectors and dismantling their organizations. On the shoulders of this forcible change in the balance of class forces, the dictatorship turned Chile into a brutal laboratory for capitalist experimentation. Under the military boot, the policies promoted by the “Chicago Boys” reorganized the economy and society.

In Chile—unlike other countries in Latin America in the 1980s and 1990s, such as Argentina or Bolivia, which witnessed the victories of mass, popular struggle over the ruling juntas—the transition from military rule to formal (bourgeois) democracy was a product of political pacts negotiated largely within ruling-class circles. This allowed the institutional arrangements built by Pinochetism to remain largely intact.

A clear example of the character of this transition, codified in the 1980 constitution, guaranteed the impunity of those politically and materially responsible for the regime’s murderous repression. A considerable part of the intelligence apparatus of the dictatorship, the CNI (National Intelligence Command), was integrated into the army. The Armed Forces remained a central institution of the new regime, and their command structure was maintained with Pinochet himself as Chief of the Army until March 10, 1998, after which he became senator for life. He was never tried. To complete this “custodial democracy” the armed forces were guaranteed the continuation of financing from ten percent of foreign copper sales by Codelco (the state-owned company that controlled the production of cooper, Chile´s main export).

This Chilean transition was largely made possible by the role of the parties that would later form one of the two fundamental coalitions of the custodial-democratic regime, the Concertación. They were the Democracia Cristiana, the main party of the bourgeoisie before the military coup, and the Partido Socialista, the social-democratic party of Salvador Allende, which by the mid-1980s had committed itself to a negotiated transition. Between 1983 and 1986 the country was shaken by an important rise in class struggle. However, this energy was largely contained through the institutions of the 1980 constitution. The dictatorship called a plebiscite within this framework. Therefore, it was limited to the question of whether Pinochet would continue as president, “Yes” or “No.” This left intact the institutional structures of the dictatorship, with the exception that an election would be called to form a bicameral National Congress, regardless of the result, thus integrating the political parties into the functioning of the regime.

The Partido Socialista and the Democracia Cristiana accepted the rules imposed by the dictatorship and together with other minor parties formed the “Coalition of Parties for No.” The Partido Comunista, with significant influence in the unions, initially rejected the regime’s maneuver but finally formed part of the process. Among the political forces that campaigned for the “Yes” vote were the parties of the Chilean right— that later formed the coalitions that brought Gabriel Boric’s predecessor, Sebastián Piñera, to power—mainly the Unión Democrática Independiente and Renovación Nacional.

In 1988 and 1989, this plebiscitary process gave birth to the custodial-democratic regime, in which the repressive apparatus retained a central and privileged role. The Armed Forces and the Chilean police, the Carabineros, were fundamental institutions of the new regime. In parallel, the system of political parties was consolidated around two big coalitions: the Concertación and the right. The first governed from 1990 to 2010, and then again from 2014 to 2018, now under the name of Nueva Mayoría and incorporating the Partido Comunista. The second governed under Piñera between 2010 and 2014 and from 2018 until March 11, 2022, the end of Piñera’s term. Both coalitions fundamentally preserved the structure inherited from Pinochetism, and the changes of government changed nothing fundamental about the model.

The political stability granted by this institutional order also consolidated the economic model inaugurated by the Chicago Boys. The consequences of this have been profound. Chile is a deeply unequal country with strongly pro-employer legislation. According to the ILO document Working Conditions in a Global Perspective, the Chilean labor market stands out for a high degree of temporary contracts (29 percent of the total) and part-time work grew from 5 percent to 17 percent between 2000 and 2015. More than 50 percent of workers work more than 48 hours a week, and 20 percent work more than 60 hours. Employment in the private sector is characterized by low coverage of collective bargaining compared to the region, with only 17.9 percent of private sector workers under collective contract conditions. The comparable figure in Argentina reached 49.4 percent in 2018. This reflects the establishment of collective bargaining by firms and not by industrial branches, and the overall balance of class forces. These conditions go hand in hand with the highest level of household indebtedness in the entire region. According to figures from the Central Bank of Chile, household debt has grown systematically, reaching 75 percent of disposable income in 2019. This compares to a figure around 50 percent in Brazil and Colombia and 37 percent in Mexico in 2020. All this within the framework of a total commodification of all the essential elements for life such as healthcare, education, housing, transportation, etc.

The streets

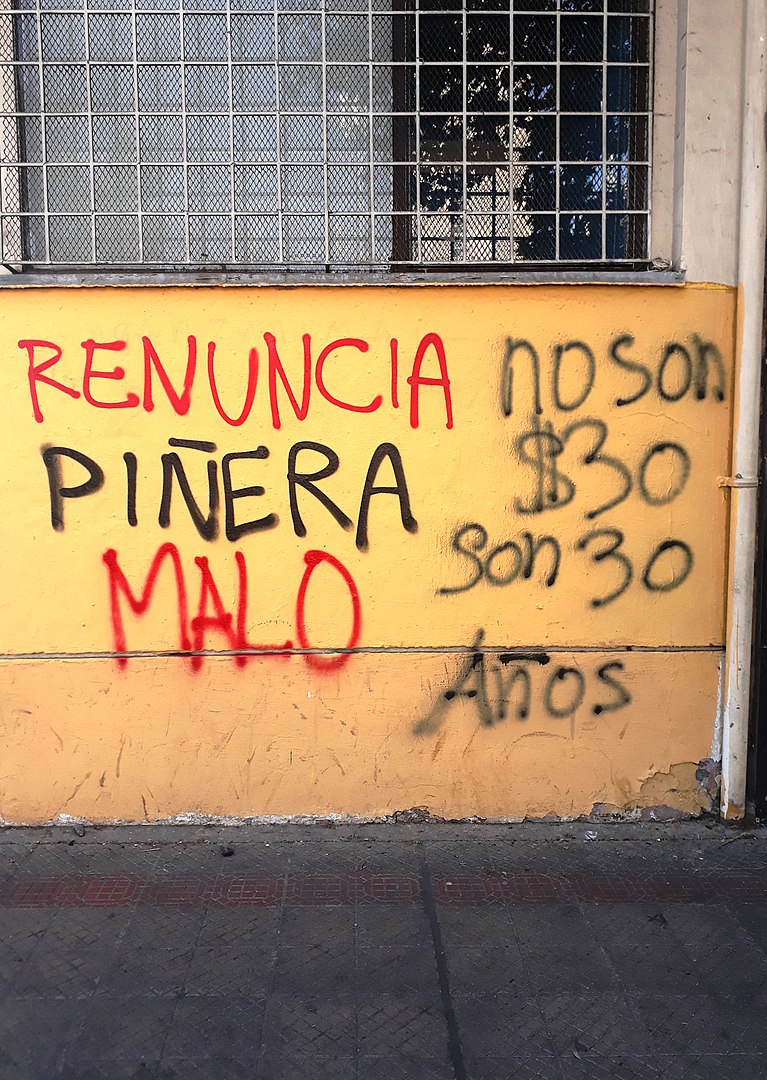

It was precisely against these conditions that the October 2019 rebellion broke out, expressed in the slogan “It’s not 30 pesos, it’s 30 years.” Thirty pesos refers to the rise in the price of the subway ticket which led to the evasions organized by high school students that sparked the rebellion. Thirty years refers to the regime.

Although the notion of a “social outburst” (“estallido social”) became a popular way of framing the events—partially reflecting the spontaneous nature and the immense force unleashed—the Chilean October has a thread of continuity with the struggles against the model that had been gaining strength for more than a decade, while at the same time constituting a quantitative and qualitative leap. Outstanding among these more sectoral struggles were those carried out by high school students and then university students in 2006 and 2011 respectively, the feminist tide, the fight against the Administradoras de Fondos de Pensión (AFP, Pension Fund Administrators, the private financial institutions that administer pension funds in Chile), and strikes by different sectors of workers such as dock workers and teachers.

These struggles had already generated shock waves in the political and institutional arrangements, leading to some changes. In 2013 the Concertación sought to broaden its base by incorporating the Partido Comunista, forming the Nueva Mayoria coalition. In these years the Frente Amplio emerged, bringing together several additional formations of the Left, many of which had emerged from the student movements or as splinter groups from the Partido Comunista. This emergent formation had an electoral breakthrough in the presidential election of 2017, obtaining 20 percent of the vote and expressing the growing discontent with the ruling duopoly.

It is important to situate the Chilean rebellion in an international cycle of rebellions. Between 2018 and 2019 important episodes of class struggle took place in France, Hong Kong, Sudan, Iraq, Lebanon, Nicaragua, Puerto Rico, Ecuador and Colombia, among others. Beyond the specificities of each process and their differences, all of them combined democratic and social demands which had their roots in the 2008 crisis and its consequences. While Chile had remained on the sidelines of the previous continental rebellion, episodes in Ecuador, Argentina, Venezuela, Bolivia, etc., had produced a turn to the left in most of Latin America that had a distorted expression in the “pink tide” governments of the first decade of the 2000s.

Nonetheless, when Chile re-entered the scene, it did so with memorable force. The events that unfolded from October 18, 2019 can be characterized as a semi-insurrection. It was a spontaneous, popular uprising without singular leadership, with an epicenter initially in Santiago but quickly spreading to all regions of the country. In the capital and the poor and working-class neighborhoods that surround it, barricades were erected and for weeks there were almost constant clashes with the repressive forces of the state. These scenes were repeated throughout the country. Plaza Italia, renamed Plaza de la Dignidad, in the heart of Santiago, became the center of action with daily battles with the police and demonstrations of hundreds of thousands along Alameda, the main avenue at the center of Santiago.

The popular and spontaneous nature of the uprising included an important and even defining participation of the working class through two general strikes and the development of grassroots strike committees. In addition, a huge youth vanguard confronted the police and military from the outset, arousing the sympathy of broad sectors of the population and, as a counterpart, fueling the repudiation of those very institutions that had played such a prominent role in the regime.. Embryonic forms of self-organization and deliberation appeared in large parts of the territory, including popular assemblies and councils (cabildos), and strike committees.

In the streets and spaces of deliberation the revolution developed its “program,” a series of social and democratic demands that responded to the precariousness of life and aimed at dismantling the legacy of Pinochetism and the 30-year model. It expressed demands that formed a fundamental part of the struggles of the entire previous period, such as the elimination of the AFPs, the end of job and life insecurity, free education, the agenda of the feminist movement, the demands of the indigenous Mapuche people and their right to self-determination, the end of repression and impunity. These elements were articulated around two central points: “Piñera out!” and a call for a Constituent Assembly.

The participation of the organized working class was largely diffused in the broader popular uprising. This represented a limitation of the process, since despite the fact that the barricades and mobilizations greatly interrupted the circulation and the normal functioning of the economy, the struggle did not have as its epicenter the points of production. Thus the key sectors of the economy largely continued to operate. Interrupting work and therefore the flow of profits, especially in sectors such as the cooper industry, would have greatly strengthened the movement.

The enormous potential of working-class action was demonstrated in the general strikes. On November 12, on the initiative of the dock workers and with the pressure of the mobilization in the streets, the Central Única de Trabajadores (CUT, Unified Workers Center) and the Mesa de Unidad Social (MUS, Social Unity Board, a body that coordinates social movements), called a general strike. That day was perhaps the most important of the entire process and left Piñera on the brink of falling. However, the leadership of the CUT and the MUS (with a significant presence of members of the Partido Comunista and the Frente Amplio) ended the strike, giving a reprieve to Piñera at the time.

The institutions

The general strike of November 12, 2019 marked a turning point for the regime. From the beginning of the outbreak, the Piñera government had unleashed brutal repression. According to the National Institute of Human Rights, one month after the start of the rebellion, the repressive forces had murdered 5 people and injured 2300, of whom 220 had severe eye trauma and 1100 legal complaints had been filed against them for torture and more than 70 for sexual crimes. The government had also tried to give some concessions, such as a law that established a 40-hour work week. But none of this stopped the mobilization.

Different political forces were looking for an institutional solution. On October 28 Piñera had carried out a ministerial change, and the Frente Amplio responded with a statement calling for a dialogue with the new interior minister, Gonzalo Blumel. The Partido Comunista and the Frente Amplio multiplied their expressions of condemning “violence” (by which they meant by the forces of popular insurrection). The former presidential candidate and spokesperson for the FA, Beatriz Sánchez, explained on a television interview that “Chile is not changed through looting and arson.” The strike of November 12 accelerated these efforts.

On November 15 congress members representing the government and the opposition announced the “Agreement for Social Peace and the New Constitution,” signed by representatives of the former Concertación (i.e., the Partido Demócrata Cristiano, the Partido Socialista, the Partido por la Democracia, and the Partido Radical), along with representative parties of the right-wing coalition, Chile Vamos (Renovación Nacional, the Unión Democrática Independiente, and Evopoli), and major constituent parts of the Frente Amplio (including, Revolución Democratica, the Partido Liberal, and the Partido Comunista) and Gabriel Boric, in a personal capacity.

This pact, reached behind the backs of the people, established the call for a plebiscite in April 2020 to approve or reject drafting a new constitution and to define whether it would be done by a Mixed Convention (made up in equal parts of current parliamentarians and elected citizen representatives) or a Constitutional Convention made up entirely of elected representatives. In addition, it established the requirement that two thirds of the members of the “Convention” were needed to approve any law. In this way, the right could veto any advance by winning one third of the seats. The election of convention delegates was set for October 2020, under the then-existing electoral system.

On the other hand, on November 19, a group of ten members of congress belonging to the Partido Socialista, the Frente Amplio, and the Partido Comunista presented articles of impeachment against President Piñera. With the pact and the articles of impeachment, the parliamentary left sought to direct the two main demands of the streets (“Piñera out” and the Constituent Assembly) down an institutional path.

Assessing the role of these forces in this period is critical to understanding current dynamics and political prospects. This must be done in the general framework of an assessment of the balance of political and social class forces. In November 2019 the situation was clearly favorable for the further development of the rebellion. Piñera’s government was cornered and his coalition in crisis. The repressive forces of the regime had failed to contain the fighting in the streets, and their image in the general population had fallen to an all-time low. Opinion polls carried out at the end of October showed that Piñera’s approval ratings had fallen to 13 percent while 79 percent rejected him and 69 percent believed that the police and the Armed Forces had abused their power. The general strike of November 12 demonstrated the immense strength of the working class and the people, and there were still no signs of wearing down of the mobilization process. From this perspective, the institutionalization efforts had a clearly regressive role. The institutional initiatives of the Frente Amplio and the Partido Comunista were far behind not only the needs, but also the possibilities of the moment.

The fall of the Piñera government was a concrete possibility. This would have dealt a severe blow to the regime as a whole. Unlike Argentina, Bolivia, Peru, and other Latin American countries, in Chile’s contemporary history no governments have fallen due to popular mobilization. This achievement would have greatly weakened the right in particular, and would have strengthened the confidence of the mass movement in its capacity for action. A Constituent Assembly under these conditions would have had greater room for action against a weakened regime. The fall of Piñera was a fundamental step to end the impunity of the repressive state apparatus.

To the contrary, the pact gave the government breathing room and allowed it to strengthen the repression. It is no coincidence that after the pact there was a legislative offensive to criminalize social protest. One of the main initiatives in this sense was the so-called Anti-Looting Law, which classified as a “crime” and as “public disorder” common practices of the ongoing social protests, such as the interruption of traffic and barricades. This meant the possibility of sentences from 541 days to five years in prison, and gave repression a new legal instrument. The bloc of the Frente Amplio in the Chamber of Deputies voted in favor of this law and later had to apologize in the face of popular repudiation.

In view of all this, it is difficult to maintain the position that the actions of the Frente Amplio during the rebellion allowed for a strategic convergence between the social movements and the Left in the institutions. On the contrary, the parliamentary Left acted in the sense of stopping the mobilization and diverting it towards the institutions, renouncing the main demand of the street (“Piñera Out”) and accepting a conditioned version of the Constituent Assembly. Contrary to what has been written elsewhere, the Frente Amplio acted to save the regime, not to replace it.

From the uprising to the elections

With the Agreement for Social Peace and the New Constitution the regime tried to channel the rebellion through the institutions. Its goal was to take politics out of the streets and return them to the halls of parliament. However, the development of the electoral calendar (delayed by the pandemic) expressed the magnitude of the changes that had occurred in Chile. The “Chilean October” opened a new stage that institutional maneuvers could not close, since it meant a decisive change in the balance of class forces.

This profound change was bound to find some kind of expression even in the electoral field. And it did. A year after the beginning of the rebellion the plebiscite for the new constitution marked an overwhelming victory for the “Approve” option with almost 80 percent of the votes, followed by a massive celebration in the Plaza de la Dignidad, which showed signs that the capacity of mobilization was still very high.

This new reality expressed itself once again in the election for the Constituent Convention in May 2021. There the right-wing coalition (which Kast’s Partido Republicano had joined) obtained 20 percent of the votes and was far from the third of the seats needed for veto power. This collapse of the governing right also happened in the elections for governors and mayors that were held on that date. The other fundamental coalition of the Chilean regime, the former Concertación, obtained less than 15 percent of the votes. These results demonstrated the crisis of the political regime and the traditional parties.

At the same time, there was evidence of a turn to the left, capitalized by the front between the Partido Comunista and the Frente Amplio and by the independent sectors, fundamentally the Lista del Pueblo. The latter emerged organically out of the rebellion, and many of its candidates were well-known activists, yet it had a diffuse political program unified broadly by a discourse of a needed rupture with the representatives of neoliberalism. Taken together, the Frente Amplio and the Lista del Pueblo obtained around 35 percent of the votes, giving a significant weight to the broad Left in the Convention. In general terms, the perspectives of “political independence” and “rupture” reflected the profound rejection of the regime as a whole and resulted in 65 of the 155 elected seats being occupied by candidates who ran outside the traditional parties.

A third electoral moment was the presidential election in its first and second rounds. An important element was the unraveling of the Lista del Pueblo between the election of the Convention and the presidential election. The Lista del Pueblo was built on politically unstable foundations—as previously noted, while it had candidates strongly linked to the rebellion, the principled and programmatic basis of agreement was always diffuse—and it made a series of political errors and was tied up in scandals that showed the limitations of a purely electoral phenomenon. One consequence of this was that the front between the Frente Amplio and the Partido Comunista arrived at the elections as the only electoral reference point for those supportive of the rebellion.

On the other side of the political spectrum, the right-wing coalition continued to crumble, plagued by internal contradictions and the massive rejection of Piñera. In this context, Jose Antonio Kast and his Partido Republicano, now split from the coalition, appeared as the main alternative on the right. The result of a first round, in which no candidate exceeded 30 percent of the votes, can be summed up as a reflection of the debacle of the historic coalitions. Thus, in the polarized first round Kast and Boric received 27.91 percent and 25.83 percent of the votes, respectively. The “outsider” candidacy of ultra-neoliberal businessman Franco Parisi—who campaigned from the U.S. relying upon an anti-political discourse based on individual entrepreneurship—came third with 12.80 percent.

Between the first and second rounds the dynamic that had shaken the country since October 2019 returned. The need to defeat Kast—the representative of the right and the regime—and to defend the process moved millions. Voter turnout increased by around 10 percent, over a million people more than in the first round. This is the decisive figure to understand Boric’s triumph, why he won with 55.87 percent against 44.13 percent for his rival. The result expresses a strong polarization, but with a clear majority of those who seek to definitively break with the legacy of Pinochet and the 30-year regime. This was visible in the massive celebrations when the results were known. However, it is worth noting, that the right has found a new representative in Kast, with his program in defense of the status quo and the model, and his racist, anti-feminist and anti-LGBTQ discourse.

Perspectives

The October rebellion shook the foundations of the political regime and changed the balance of class forces. The Chilean regime cannot be rebuilt on its previous foundations, as was made clear in the electoral process with the collapse of the two traditional coalitions. However, the bourgeoisie and all the defenders of the status quo are looking for a way to rebuild on new grounds. This outcome of the process will be conditioned by the presence in the streets of a mass movement that is yet to be defeated.

Kast’s defeat in the second round of the presidential election was undoubtedly a necessity, but this cannot obscure the understanding of the general dynamics of the events of the last two years. The Frente Amplio gradually became the manager of the stability of capital during and after the rebellion. It raises a program that takes some of the demands of the uprising, but adapts them to the need for governability of a regime in crisis, moving away from the impulses of the revolt and speaking the language of “possible” changes. If the Boric government disappoints those demands, this will undoubtedly strengthen the position of the right. The initial signs are not encouraging. Boric’s cabinet announcement on January 22, 2022 shows that he has launched a new coalition. Far from turning to the left, he has shifted to the political center, insisting on bringing in forces and characters who have received popular repudiation in all of the last electoral processes. Seeking to expand the government’s support base, Boric has not sought greater participation from the social movements, from the popular forces, or from the expressions that emerged after October. On the contrary, key positions in the new government structure were given to conservative forces, particularly in the economic field. The incorporation of the Partido Socialista with four ministries and other forces such as the Partido por la Democracia and the Partido Radical is clearly a message to the economic powers of the country. At the same time, it is an example of an attempt to recompose the regime, adapting it to the new balance of forces.

In this context, those of us who seek a radical transformation must remain mobilized to achieve the demands of October. At the same time, a central conclusion of the entire process is the need for a revolutionary political alternative. The events show that there is enormous energy in the working class and the mass movement, beyond the limitations that we have pointed out in this article. However, a political instrument is needed to concentrate that force and prevent it from dissipating and wearing down. The conditions opened by the rebellion pose great opportunities to resolve this pending task. At the same time, history shows us once again that we cannot wait until the time of the insurrection to build such an organization.

Featured Image Credit: Leon Hernandez Image modified by Tempest.

Categories

We want to hear what you think. Contact us at editors@tempestmag.org. And if you've enjoyed what you've read, please consider donating to support our work:

DonateJoaquín Araneda and Luis Meiners View All

Joaquín Araneda is a member of the Movimiento Anticapitalista, Chilean section of the International Socialist League. It has been dedicating its efforts and its intervention to build revolutionary organization in the heat of the current developments, and in the struggles for the October agenda. Luis Meiners is a socialist activist and sociologist, member of the Tempest Collective and the Movimiento Socialista de Trabajadores (MST), Argentinian section of the ISL.