In search of resistance

A review of The World Turned Upside Down

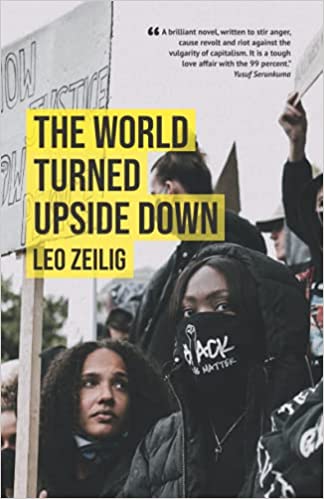

The World Turned Upside Down

by Leo Zeilig

Ibadan, Nigeria: Books Farm House & Publishers, 2021

“We have already seen the first wave in 2011 in North Africa and the Middle East, but new movements are developing. A further, deeper intifada, incorporating a far larger swathe of the planet. Intimations of the future, I think …”

Leo Zeilig’s latest novel is a wild ride. From the opening pages about a wealthy banker’s violent death to an ending overshadowed by the threat of fascism and the hope of resistance, The World Turned Upside Down is an exciting read. But more than a page-turner, it is a powerful reflection on a world in crisis and one woman’s urgent voice, framed by the key upheavals of our time.

Published on the ten-year anniversary of Occupy Wall Street and the Arab Spring revolutions, the novel is anchored in the demands of those struggles. The protagonist, Senegalese-born, London-based professor Bianca Ndour, rails at inequality, oppression, and human misery, taking particular aim at the ravages of neoliberalism and the corruption of the 1 percent. But the arc of history—its victories and defeats—also animates and enrages her. Bianca swings between hope and a deep pessimism, both for the world and for her relationships.

“The best chance we had was 1917, the defeat in the 1920s is still with us…. Everything else that was done was done in our name…. Where we stood bold and socialist in 1905, even bloodied and defeated in 1906, and worse in 1914, this was temporary. In 2011 our defeat gives birth to catastrophe.”

The novel unfolds in the present day at breakneck speed. The murders of members of the 1 percent continue. Meanwhile, an online blog, The Revealer, appears, detailing the explosion of struggle and promising to “rip the HEADS off the global bourgeoisie.” Bianca herself has her own outlet, having stumbled on a vehicle for a worldwide platform with a bestselling self-help book she contemptuously dismisses as “New Age garbage.” Speaking to an audience in Dakar, Senegal, she laments to herself, “The hunger for change was insatiable—yet they had it all wrong, and I had helped in the mystification.”

At her Dakar speech, it comes to light that another murder has taken place, this time of a local businessman originally from France. Later, a series of fires—nicknamed “comrade” by the poor—rips through the wealthy neighborhoods of Cape Town, South Africa. As the destruction mounts—and the Revealer continues to rage— Zeilig unspools the mystery of the novel: Is the coincidence of the murders and Bianca’s travels accidental, or is something else afoot? Who is behind The Revealer? Amid the unfolding crises, where is Bianca headed? Refusing to condemn the killings of the rich, Bianca reveals glimmers of admiration for The Revealer and its “hit list” of the world’s 1,635 billionaires.

Bianca is not an easy heroine. Self-aggrandizing and sometimes cruel, she compares herself alternately to Malcolm X, Nelson Mandela, and the Pope. She lacerates almost everyone around her, from global figures to her colleagues and lovers. But she also confronts her doubts with a clear-eyed honesty, asking herself, “In a year of organization, with the right action, this could all be changed—the world turned upside down. How had I allowed myself to despair, even for a moment?”

The novel offers some clues as to what makes Bianca tick as it revisits her past. Bianca is of Senegalese and Scottish descent. Her father—“a man of contradictions”—is white and works for Shell Oil. He impresses upon Bianca and her twin sister the hazards posed by drilling for oil as he reads aloud from Walter Rodney’s How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. Later in the novel, we come to learn of a pivotal event from Bianca’s childhood in Port Harcourt in the oil-producing region of Nigeria, which results in environmental destruction and loss of life. “How strange it was,” says Bianca, “to get Rodney, Huey P. Newton, Stokely Carmichael, and Kwame Nkrumah in a Scot’s accent, from a man with a white, ruddy complexion and red-brown beard, whose day job was to facilitate the official, post-colonial pillage of Nigeria.”

These early contradictions form a central thread running through the novel: her love of a woman that causes her pain—“each space in my life had been colonised by her”—and the knowledge of capitalism’s destructive power, alongside vacillating doubts about the capacity for change. She is disgusted by the wealth and stultifying atmosphere of the university where she teaches, yet recognizes that it provides her with a ready audience for her ideas. Her personal contradictions are also stand-ins for those of capitalism itself, and the search for answers mirrors the ups and downs of Bianca’s failed marriage and falling in love again. Pain is a constant in the world we inhabit. As Bianca puts it, “We can imagine the end of the world, but not the end of misery.”

Given this analysis, Bianca has no choice but to reject short-term solutions. Addressing a group of striking cleaners and security guards at her university, she urges them to believe in their ability to win, while declaring that the answer lies in the overhaul of the system. The misery of austerity, pollution, and war spans the entire globe, taking different form from place to place—a collapsed factory in Bangladesh, the murder of strikers in South Africa, the gas flaring of oil wells in Nigeria, land grabs in Kenya—but tied together by a capitalist class, the 1 percent that she denounces.

Here lies the core logic underpinning the novel’s frenzied pace. Zeilig is a novelist and historian, a revolutionary socialist who has long written about class struggle and the individuals and movements that push them forward and confront their defeats. The World Turned Upside Down is a wonderful book with some important insights beneath the dizzying turn of events: that the system must be overhauled in its entirety, that there is joy in taking action, and that amid the unhappiness are individuals trying to make their way as best they can. This is a must-read book with both a protagonist and message memorable long after its final pages.

Categories

We want to hear what you think. Contact us at editors@tempestmag.org.

Lee Wengraf View All

Lee Wengraf is an activist based in New York City, contributing editor to the Review of African Political Economy and author of Extracting Profit: Imperialism, Neoliberalism, and the New Scramble for Africa (Haymarket Books, 2018).