Building a mass movement with no apologism

The Left and the Communist Party of China

In late September 2021, the Asia and Oceania subcommittee of Democratic Socialists of America’s (DSA) International Committee voted on whether to sign on to a joint statement on the disbanding of the Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions (HKCTU). The statement was signed by a wide coalition of regional left-wing organizations and organizers, including hundreds of labor unions and socialist organizations from Bangladesh, Taiwan, South Korea, India, Pakistan, Indonesia, and the Philippines.

Even though condemning the disbanding of a labor union of 160,000 members due to Communist Party of China (CPC) intimidation was a unifying moment for much of the regional Left, those of us from the International Committee (IC) who voted in favor of signing on were outnumbered by those in opposition. The reaction from some DSA leaders is best described as gleeful.

Simultaneously, a current of pro-CPC opinions were gushing forth from the Qiao Collective-sponsored “China and the Left: A Socialist Forum.” Attendees included many of DSA’s top leadership. Many comrades who I deeply admire, who had been rightfully elected to the National Political Committee (NPC), were among the attendees of the conference. As someone who had supported the Renewal slate for NPC elections last summer due to agreement with their vision of building a mass movement, I was shocked when those same comrades harmed the U.S. Left’s capacity to build a mass movement.

A few years ago, I facilitated a restorative process that dragged on for many months. A community leader with a sloppy understanding of East and Central Asian identities and politics set our community on fire during a town hall. He incensed many Taiwanese and Tibetan community members by suggesting they were part of the Chinese diaspora, alienating individuals from both groups. His words – ones which are parroted and agreed on by elements like the Qiao Collective – were received as deeply offensive microaggressions that insulted the fabric of their lived experiences.

I was approached to facilitate the process of addressing the harm that had been done. This began with one-on-one meetings with many of the individuals affected that aimed to identify paths forward with respect to their own agency. Many individuals were unwilling to participate in any further conversations. They wanted nothing but to be as far away from the offending community leader as possible. In effect, they dropped out of community involvement. Others wanted the community leader to recognize the harm that had been done – and why his mistake had been so deeply offensive.

It took multiple subsequent meetings to reach that point in a way that was convincing to some of those seeking repair. As with many restorative processes, much of the harm done remained inadequately addressed to many of those most impacted.

Much of the restorative process involved education. Like many leaders in the West who lack direct experience in the region’s diaspora politics, he was not equipped with adequate knowledge to recognize the degree of the harm he had caused. I’ll outline some of the knowledge bases he lacked that undergirded the restorative process.

Chinese Imperialism and diaspora politics

In Taiwan, there is a concept called 台灣主題意識 (“Taiwan-centric consciousness’) that developed largely since Taiwan threw off the colonial yoke of the anti-communist White Terror and U.S.-supported right-wing dictatorship that had previously governed mainland China with fascistic tendencies. The idea essentially refers to the need to center Taiwan in discussions about Taiwan, not referring to the nation in all its complexities as simply a verbal tic in conversations about China. It identifies, correctly, that China has historically been an imperializing force oppressing the Hakka, Hoklo, and Indigenous populations on the island. Referring to Taiwan only as a function of China – never on its own terms, in all its diversity – perpetuates imperialist understandings of a nation home to 23 million people.

Many Taiwanese view the CPC as the most immediate imperial force bent on invasion – the latest wave of colonization, following Kuomintang, Japanese, and Western imperialisms. That is true also of many Taiwanese workers in the United States. Many Taiwanese live and work as immigrants, feeling state-imposed pressure to build homes in case their relatives from Taiwan need to flee as refugees from invasion by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). The long shadow of the CPC looms wherever they go, dominating their lives.

Meanwhile, it is also necessary to understand the history of settler-colonialism in Tibet. Prior to the PLA’s invasion and consolidation of control over the wide expanse known as Tibet, the steppe was loosely governed at best. Kham and Amdo, two regions that now overlap with provinces in China’s core including Sichuan and Yunnan, lived entirely different lifestyles from Tibetans in U-Tsang – now called the Tibetan Autonomous Region under CPC governance. U-Tsang, as many communists often note, was marred by patriarchal and abusive power structures presided over by theocratic elites. The autobiography of Tashi Tsering is a powerful telling of one Tibetan communist, who was sexually abused by those elites and celebrated the New China, but was later imprisoned as a counterrevolutionary when he returned to his home country to take part in the ongoing Revolution in Tibet.

However, despite this horrible history of oppression predating the Maoist period, many Tibetans have now suffered from being separated from their homes for generations. Like Indigenous people in the United States who have been removed by reservation and extermination, many Tibetans have been displaced from their land and have not seen their ancestral homes since the PLA invasion of the 1950s. Others, especially Khampas and Amdowa, saw their nomadic lifestyles developed for millennia before the rise of the feudal Tibetan theocracy forcefully ended by the CPC. That cultural destruction of Tibetan heritage occurred alongside the seizure of treasures from temples. In U-Tsang, many Tibetans unable to flee saw ninety percent of monasteries destroyed before, during, and after the Cultural Revolution by the CPC.

The number of Han residents has increased in U-Tsang, as has the number of economic opportunities that Han residents benefit from at the expense of Tibetans. Han residents dominate local development in U-Tsang. As Emily Yeh has shown, Han colonials are systemically prioritized over Tibetans through domination of technology, prestige language usage, and willingness to participate in destructive neoliberal development that has spoiled the land and transformed Tibetans into a renter class on their own land. The way in which economic domination of the region has manifested in a sense of superiority for many Han residents shares many common traits of the colonial mind identified by important writers like Albert Memmi in The Colonizer and the Colonized and Frantz Fanon in The Wretched of the Earth. In the aftermath of the 2008 riots, where CPC security forces cracked down on Tibetan protesters, the Lhakar movement was founded in which Wednesdays were selected to celebrate Tibetan identity through speaking Tibetan, wearing chuba, and non-cooperation with Han colonists on Tibetan land. When identity is criminalized, the very motion of expressing identity can become a political act against settler-colonization.

These realities and political backgrounds are close to many Tibetans’ deeply-held convictions and worldviews. An understanding of the CPC based on the harm done to their families, to their relationship with their own country, exists at the heart of many Tibetan refugees’ self-conceptions. This includes many Tibetans who live as immigrants in the imperial core, who struggle with many of the same struggles shared by other brown immigrants facing the power of the U.S. state.

Learning from China or with China?

These histories and ongoing violence may seem irrelevant to the U.S. Left. Many would argue these are distractions and that an internationalist Left should show only solidarity with the struggles of China against U.S. imperialism. However, to suggest that defending China against U.S. imperialism should be our only concern in internationalism toward China is to severely underestimate the extent to which the international is also the domestic. Many of our comrades, in the trenches of the war against U.S. imperialism, are the ones most directly impacted by the CPC’s ongoing colonialist actions learned from Western models. The CPC isn’t just over there; it’s right here, right next to us, affecting our neighbors and our communities. Because we should care about our comrades, we should care about what affects them – including CPC violence.

The CPC’s actions against minorities matter to huge segments of people in the United States, including Taiwanese and Tibetans. China also has a long history of domination over Vietnam before and after the CPC’s takeover, which is remembered and despised by many Vietnamese refugees who now work in some of the lowest-paid and most-exploited jobs funneling the U.S. capitalist machine. The CPC also heavily funded the Khmer Rouge in the 1970s that murdered or starved a quarter of all Cambodians, which has a direct connection to the plight of Cambodian-Americans. Those who fled as refugees from the Khmer Rouge and invasion downward assimilated into ghettos in places like the Bronx and urban Los Angeles. Many of those Cambodian homeworkers, who were and continue to be exploited in shadowy cesspools of capitalist cannibalism like the New York City garment industry, have relatives and other loved ones that remain in a Cambodia that is still heavily underdeveloped and traumatized by history. That is particularly the case for people who live in rural Cambodia, who still face the threat of land mines planted by Chinese forces.

As a former harassment and grievance officer in DSA who has facilitated restorative practices between community members before, who has witnessed accidental endorsement of CPC ideological beliefs that have contributed to harm in diaspora families inside the imperial core lead directly to alienation, I am concerned about how limited these dimensions are in the anti-imperialism of some on the U.S. Left.

For example, the lived experiences of our own comrades with direct experience with the CPC are not honored sufficiently in Ryan Mosgrove’s article in the Washington Socialist. Mosgrove outlines a number of important realities in his piece. The most significant is the context in which much of the U.S. foreign policy establishment has ramped up the gears of a New Cold War with the People’s Republic beginning with the Pivot to Asia, which has only increased in military armament during the Trump and now Biden-Harris Administrations. Chinese expansionism has played a large role in the anxiety of U.S. imperialists in developing this new bipartisan paradigm. As early as 2009, on the eve of the Pivot to Asia, Robert Gates was openly discussing the need to “counter” Chinese military capabilities to maintain U.S. hegemony.

Mosgrove also called out the particularly abhorrent piece by Russell Mead in February 2020 that referred to China as the “Real Sick Man of Asia,” which plays on orientalist and racist tropes deeply implicated in both past and present violence against Asian-Americans. The New Cold War always should be forcefully repelled, refuted, and resisted, as a status quo that contributes only to more violence both internationally and domestically.

However, there are a number of important elements that Mosgrove mistakes. One of these is describing the context in which the Qiao Collective was formed. The Qiao Collective, according to Mosgrove, was formed in the context of the uptick in anti-Asian violence that has occurred since the beginning of the pandemic. Qiao’s work long precedes the pandemic. If Michelle, a founding member, argued that the Collective was formed in 2020, they misrepresented the organization.

The Qiao Collective has been a thorn in our side for much longer. When I was a student participating in solidarity actions with the anti-extradition movement at National Taiwan University in 2019, the Qiao Collective was publishing critical propaganda pieces against our movement. They were a reactionary Twitter and Facebook presence, fluent in leftist jargon, but largely ineffectual due to their complete lack of connection with movements on the ground. Unlike the Lausan Collective, which had and continues to have real organizing ties against imperialism and authoritarianism, the Qiao Collective possessed no organizing base. Qiao sought nonetheless to combat Lausan and its affiliation with the movement by strategically targeting leftist spaces with little personal knowledge of Asia-Pacific solidarity. They insert Han nationalist talking points into leftist discourse through events like “China and the Left: A Socialist Forum.”

Another mischaracterization Mosgrove makes is his omission of hukou1 policy in his discussion of poverty reduction in China. He notes the importance of Chinese people’s agency in poverty alleviation (which should be viewed as a bare minimum for an ostensibly socialist government in power for seventy years), as well as pandemic relief, assisted by the CPC: “This aspect of Chinese life, where the CPC plays the role of civic organization, is something that is under discussion in discourse around China. It is all the more conspicuous given the role mass mobilization played in the response to COVID-19 in China.”

Mosgrove is correct. The CPC’s grassroots branches do serve a fundamental and important role in a civic organization, although it is equally important to note the way in which such branches can simultaneously exercise a surveillance function when necessary by virtue of their close proximity to residential communities. When I was a social worker in one such grassroots branch of the Chinese government, we organized events and community services for residents every day. This included holiday events, but also delivery of necessary food and equipment to disabled residents who were unable to leave their homes. These networks, facilitated by Chinese government municipal branches like the one I served in, were tapped into during the pandemic relief.

However, that is not the entire story of poverty reduction in China.

While CPC cells did play an important role for civic engagement in poverty reduction, so did the amendment of regulations to abolish the 鐵飯碗 (iron rice bowl) welfare provisions and to manipulate the 戶籍制度 (huji, or hukou, system) to provide an expansive pool of exploitable labor. The shattering of the iron rice bowl ended employment stability for 34 million employees and contributed to generational trauma resulting from economic insecurity for the families of all those whose rice bowls were destroyed. Simultaneously, the hukou system’s utility contributed to the development of a mass proletariat through neoliberalism with Chinese characteristics, as well as educational structural inequality, as private migrant schools sprung up to provide education to migrant children barred from public education in cities. The destruction of social safety provisions also has been linked to the decline of mental and physical health among millions of migrant workers and left-behind children. That was the case with many migrants and migrant organizers filling the void left by the state that I worked with in Yunnan and Beijing.

And it is also the case with many Chinese immigrants in the United States who must become part of our mass movement, who originally migrated from the Chinese countryside but eventually were funneled into U.S. imperialist networks to become labor for the capitalist engine.

These facts matter because they influence how we understand Chinese policy. If we seek to learn from Chinese experiences, which we agree is essential, we must do so with a balanced and sober understanding of the real impacts of Chinese policy. That especially is necessary with regard to the impacts of Chinese policy on the people around us, who are part of our communities. We must carefully evaluate the claims of Qiao Collective-affiliated speakers who leave out part of the story for their own convenience and interests, interests not shared by DSA in building a mass movement.

Essentially, we must do as Fabio Lanza advocates in his piece “Of Rose-Coloured Glasses, Old and New”: “confronting [discourse on China] does not mean, however, that we thus need to embrace China’s discourse about itself. It means, perhaps, that we should be open to learning from China, or rather with China.” That means learning alongside CPC in how party organizational branches can spearhead and participate in civic mobilization. It also includes learning from Chinese frameworks that remain relatively under-discussed and unknown in the West. But importantly, it means not uncritically accepting the party-state’s own mythology without a single thought paid to the harm such uncritical acceptance entails.

Internationalism and Care

We must resist the New Cold War. That is most paramount. Simultaneously, we must be careful to not endorse the CPC unconditionally when CPC policies harm our neighbors and our comrades. To do so would mean disastrous effects to both our relationships with comrades in the region, who confront imperialism every day, and in the Taiwanese and Tibetan and Vietnamese and Cambodian and other diasporas. We also must resist endorsing the idea that all of these diasporas belong to China discursively or nationally.

We must also learn to better practice care for our comrades at the forefront of the violence generated by ideas like the New Cold War. Caring about our comrades, who face increases in anti-Asian violence, includes understanding that many face racist violence from the U.S. state while their families confront the structural violence from the Chinese state. In a piece titled “Fighting anti-Asian violence cannot include apologism for the Chinese state,” former Chinatown tenant organizer and DSA member Promise Li writes that “in a globalized system of anti-Asian violence, one cannot compartmentalize anti-racist struggle within the national boundaries of certain states. The Atlanta shootings remind us that massage and sex workers—many of whom are Asian migrants—have long been stigmatized and criminalized by draconian anti-sex work agendas inherent in legal frameworks from the Chinese hukou system to US anti-trafficking legislation, often spurring them into a circuit of displacement and migration from Hong Kong to New York.”

Just as lived experience is intertwined across state borders, our internationalism must also be intertwined. Platforming Qiao’s narratives, which whitewash and erase the lived experience of our comrades, promotes an internationalism that views China as “over there”, which is dangerous in building an international, democratic socialist, worker-driven mass movement. CPC policy affects people in our organization, in our apartment complexes, in our homes. Our movement overlaps with other movements. Viewing the negative policy impacts of the CPC as irrelevant to conversations about the New Cold War shows one thing: the privilege of insulation from the impact of the CPC. It also displays a harmful assumption that China’s internal dynamics are unknowable, which contributes to orientalistic conceptions of China. If many of the people on the frontlines of the New Cold War, as well as fights against imperialism, are negatively impacted by the CPC’s policies, then those policies matter.

We cannot build a mass movement without deep, structured community care. We cannot ignore the lived experiences of others, nor what matters deeply to people in our movement, and still practice community care. Just as we should care about building coalitions with the mosaic of left-wing organizations that signed on to the HKCTU letter, we should care about how our decisions and attitudes impact others.

1. Editor’s Note: Hukou is a system of registration that designates families as residents of urban or rural areas. Descendants of peasants continue to be classed as “rural migrants” when they work in urban factory jobs, sometimes for decades. Their hukou status as rural migrants denies them and their children local social benefits such as health care and public schooling—thus shifting a substantial burden of social reproduction from the state to these “migrant” workers.↩

We want to hear what you think. Contact us at editors@tempestmag.org. And if you've enjoyed what you've read, please consider donating to support our work:

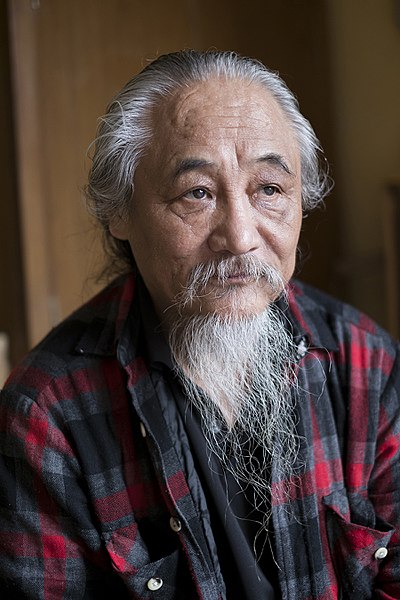

DonateTravis S. View All

Travis S. is a community organizer who has been active in social and political movements in the United States, the People's Republic of China, and Taiwan. He is a member of Democratic Socialists of America and a harassment and grievance officer for his chapter.