Striketober

Is a bigger eruption on the horizon?

The AFL-CIO declared October—“Striketober” with good reason. The summertime uptick in strikes has turned into a wave of strikes across the country this autumn. Tens of thousands of workers from a variety of industries hit the picket line last month. Compared to the historic low point in strike actions last year as the pandemic crushed the economy this is a refreshing and exciting change. It is also important that the strikes have returned to the industrial core of the economy.

Strike Fever

The largest of last month’s strikes was at John Deere, after workers rejected a tentative agreement between their union, the United Auto Workers (UAW), and the giant manufacturer of agricultural and heavy-duty construction vehicles. Ten thousand UAW members walked off the job in the early morning hours of October 15 demanding higher pay increases and no further concessions to the corporation. John Deere’s profits have risen by 61 percent over the last few years, and its CEO John C. May saw his salary grow by 160 percent during the pandemic.

The most obvious takeaway from this year’s wave of strikes is that large swaths of the working class are sick and tired of concessions, unsafe workplaces, and being worked to death. Some striking workers have referred to the endless workdays as “suicide shifts.” From the Hunts Point Terminal strike in January to the Nabisco strike in July through the John Deere strike in October—workers who’ve suffered and struggled through a year and a half of pandemic-inspired speedup—have voted overwhelmingly against concessionary contracts and hit the picket lines.

Strike fever has even infected mainstream media reporters covering the labor battles across the country. ABC News’ Terry Moran was positively exuberant in his live reporting from the John Deere picket line. After interviewing Deere strikers, he concluded, the Deere strike is “just the latest in a wave of labor stoppages across the country” and part of “a new militant spirit in the American workforce.” Surveying the burgeoning wave of strikes, Moran proclaimed, “Labor is on the march.”

Larger groups of workers may soon be joining them. Healthcare giant, Kaiser Permanente, faces a potential strike of 60,000 workers on the west coast, which could begin within the next week. And the ratification vote over a tentative agreement (TA), between the big Hollywood studios and streaming services employers and the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE), the union that represents the workers behind the cameras, is also in the spotlight. Working conditions were at the center of bargaining concerns for Union members. The recent high-profile injury and death, during the filming of the Alec Baldwin film “Rust”, due to unsafe working conditions, has put the TA under even greater scrutiny.

The strike statistics tell us only one part of the story. Liz Schuler, the new president of the AFL-CIO, told Time magazine, in a recent interview,

We have over 30 strikes happening right now. Around 100,000 workers are either on strike or have authorized a strike at this moment and so it’s the culmination of going through this pandemic, where workers were told they were essential, and now are being treated as expendable.

Since the beginning of this year, Cornell University’s strike database reports that there have been 250 strikes, involving small and large groups of workers, across the country. In 2020, as the pandemic shut down large parts of the economy from March onward, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS),

There were 8 major work stoppages beginning during 2020. This year had the third-lowest number of major work stoppages since the data began in 1947. The lowest annual total was 5 in 2009, followed by 7 in 2017.

The BLS defines a major work stoppage as involving 1,000 or more workers for a full shift, so many strikes involving less than one thousand are not recorded, and if they don’t receive any media coverage they don’t get on the radar of political activists.

Luckily there appears to be a welcome change by the mainstream media to covering these labor struggles. Every day brings news of some kind of labor struggle defying efforts to predict where struggle may break out. There’s a renewed effort to organize Amazon this time in Staten Island. A union drive is ongoing at Starbucks stores in Buffalo, New York. The faculty at the University of Pittsburgh recently voted to unionize, strike votes at airlines and among transit workers, and the list goes on. These are examples of molecular shifts in working-class consciousness that aren’t recorded as official strikes but they are the other part of the story.

Mood of resistance

There is clearly a new mood of resistance and a willingness to organize, and, in many cases, to strike. In August, nearly 4.3 million workers in the U.S. quit their jobs, no longer satisfied with low pay and long hours, in what the mainstream media has dubbed the “Great Resignation.” Former U.S. Labor Secretary Robert Reich has called it an “unplanned general strike.”

The widespread discontent with the quality of work-life is already a major economic issue, could it morph into a political crisis? Does this year’s revival of workplace activism foreshadow a major eruption in the U.S. workplace in the coming years? Right now it is hard to give a definitive answer to those questions but we can see the broad outlines of what is driving workers to reject concessions and to strike.

We can also see on some picket lines a political opportunity to push back against the backward ideas among industrial workers. Long time Minneapolis socialist, Kip Hedges reported after visiting a John Deere picket line in Waterloo, Iowa, that cheers erupted at a strike rally after a UAW committeeman (alluding to disputes between Trump supporters and others inside the plant) declared,

It’s no secret there’s been political conflict on the shop floor. But I say it’s time to put those differences aside. We need to unite against a greedy corporation, we need to unite around what we have in common and that’s that we are workers. We need solidarity.

The pastor of Faith Temple Baptist Church told Hedges that community support for strikers is strong. “Our church is all Black”, she said. “In our church of several hundred, everyone supports the strikers. That’s because our members are either on strike, retired from Deere or they have family members on strike.”

Revenge of the essential worker

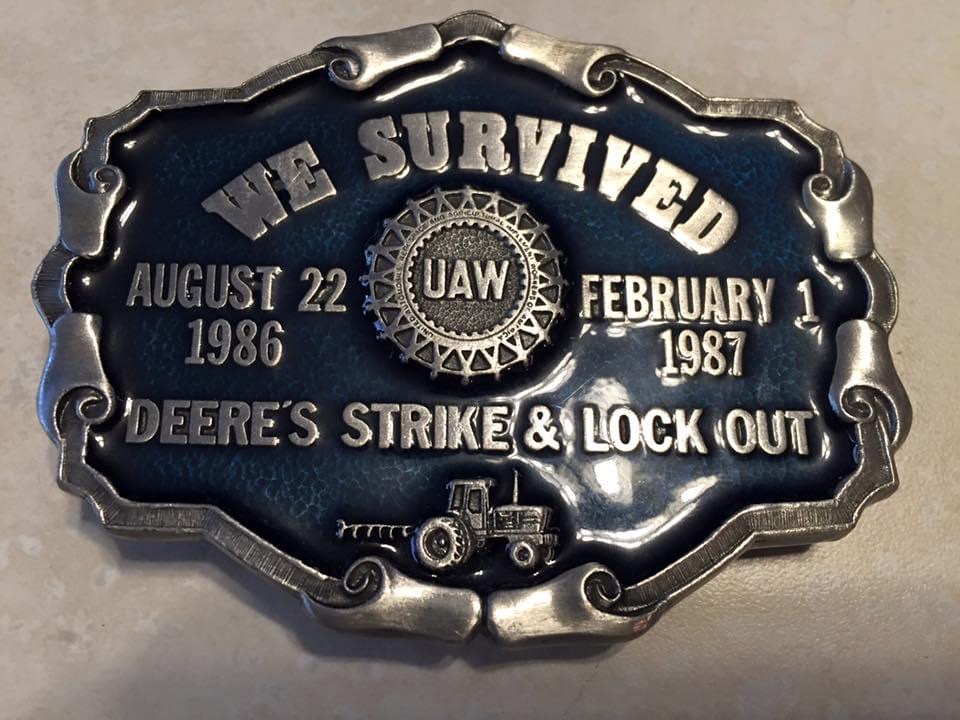

Last year’s pessimism has swung to hyperbole. Calling job dissatisfaction a “general strike” or declaring strike waves when historically few workers are actually on strike makes it harder to see what is actually happening in the working class, and to make a political assessment. We have a labor movement that’s in a terrible crisis that represents a meager six percent of the private sector workforce. Many of the unions calling strikes this year haven’t been on strike in a generation or more. The last time John Deere was on strike was in 1986; Nabisco in 1969. Many of the settlements are also mediocre and have had strikers fired after returning to work.

The strikes that have been settled and those that will be, often lock workers into long-term, no-strike contracts that make it extremely difficult to continue the battles that brought them out to the picket lines in the first place. Workers at the world-famous Heaven Hill distillery recently ended their strike and returned to work. Workers rejected the tentative agreement reached between the company and their union the United Food and Commercial Workers Union (UFCW) but the union constitution requires a two-thirds no vote to reject a contract and remain on strike. One worker told a local news crew, “We are going back for exactly what we went on strike for.”

The major unions in this country including the big industrial unions—like the UAW, where members are voting currently on whether to change their union’s constitution to have the right to directly elect the top officials of their union—are highly bureaucratic monstrosities that have pursued one version or another of labor-cooperation for so many decades, they know nothing else.

This year’s strikes are very much the revenge of the essential worker, largely economic strikes against outrageous employer demands. They are often accompanied by the rejection of proposals recommended by their own union leaders. This is one of the thornier issues that always arise in any strike where the union leadership will continue to lead negotiations but have had their tentative agreements rejected. For example, the UAW forced its members to vote four times at Volvo on nearly the same contract before it was accepted by a slim margin. Or in Seattle where leaders of the carpenters union had their members reject a tentative agreement four times before finally going out on strike. Or on November 2, 2021, when the John Deere workers rejected a second contract offer by a ten percent margin.

Solidarity and socialist politics

We can see in the current wave of strikes, the possibility of introducing a layer of strikers to socialist politics across the country. Hundreds of DSA members and other socialists have gone to picket lines, raised money, and done other forms of strike support. The national DSA call to support Nabisco strikers with contributions from strikers and reports from across the country was excellent. It has been overwhelmingly a positive experience. Strikes have broad public support right now and unions are popular especially among younger workers. The time for cautious union tactics should be cast to the wind.

Mobilizing for picket lines and fundraising for strikers flow naturally from the solidarity that socialist feel for striking workers, yet we can’t avoid the thornier political issues. Union leadership is clearly lagging behind their members. The potential power of many unions has been underutilized too much of the time, while greater gains could be made in current contract battles. “There is this grassroots push,” David Madland, a senior advisor to the American Worker Project, a mainstream Democratic Party think tank, told Time magazine, “and leaders have to catch up.”

Socialists need to actively organize rank and filers to work with union officials when they fight for us but act independently of them when they don’t. The spirit of this was captured in a picket line interview at John Deere in Waterloo. James Geiger, a 53-year-old John Deere machinist, who has worked at John Deere for nearly twenty years and was hired in as a lower-tier worker agreed to by the UAW back in the 1990s. Presaging the recent “no” vote on the second contract offer, Geiger told Time magazine, “We don’t trust the international [union]”. “They brought that lousy contract for us to vote on.”

“The international and the local union kept telling us, ‘You guys will never see a [full] pension and never see medical benefits when you retire,’” says Geiger of the UAW. “I always ask, ‘Why not? That’s what we want. Take it to the bargaining table and fight for it.’”

Unfortunately, when Seattle City Councilmember Kshama Sawant, a leading member of Socialist Alternative and a more recent member of Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), publicly supported striking carpenters in Seattle, including the rank and file rebels of the Peter J. McGuire group, she was subject to unprincipled attacks. These came not only, as might be expected, from the leader of the carpenters union, but also from DSA members. One prominent contributor to the DSA labor activists listserv said the following, “This is a lone Trotskyist leading MAGA type. Sawant, as usual seeks headlines.” This is about as close to calling Sawant a “Trotskyite-Fascist” as you can get in modern times.

At such critical moments, DSA members have to decide which side they are on, that of the labor officials or the rank and file fighting for better contracts. Such bizarre and bewildering attacks on Sawant—someone that has been a long-time opponent of Amazon’s political agenda in Seattle, and who is now facing a right-wing initiated recall campaign—is alienating not only to striking workers but to socialists who expect better from our movement.

Hopefully, this year’s wave of strikes will bring more workers out for the rest of this year and continue into next year. We need to improve our political interventions, however, to move both the labor and socialist movements forward.

Featured Image Credit: Photo by Adam SchultzImage modified by Tempest.

Categories

We want to hear what you think. Contact us at editors@tempestmag.org. And if you've enjoyed what you've read, please consider donating to support our work:

DonateJoe Allen View All

Joe Allen is a long-time labor activist and writer. His latest book is The Package King: A Rank and File History of UPS.