How IATSE got strike ready

Behind the scenes with Spring Super

Héctor A. Rivera: Can you tell us about the working conditions that are leading to this strike? It sounds like these complaints are not new. Why are IATSE workers ready to strike now?

Spring Super: There are a lot of different conditions that are creating a perfect storm of discontent. The conditions greatly depend on who you are and your job. The conditions that I experience as a make-up artist aren’t as bad as say the conditions that a production assistant would experience. But if you’re “above the line,” your experience can be much better.

I primarily work as a makeup artist on episodic television shows. The shooting schedules can be a matter of a few months to 9-10 months out of the year. During shooting time we basically don’t see our families or have lives outside of work. The average work day is 12 hours, five days a week, and we often go over 12 hours. We also do not get very much time in between days to sleep and see our families, take care of the things we have to take care of, doctor’s appointments, etc. There is no time for anything else during the week. We don’t even have enough time to get to and from work and get a full eight hours of sleep.

That’s a big part of what the negotiations are about. We are asking for more turnaround time between the end-of-day Monday and start-of-day on Tuesday, for example. We’re asking for enough time to get enough rest and take care of other things, like showering, preparing our meals, taking our children to school, whatever it is. There’s no time for any of that, so our lives sort of fall apart if we don’t have somebody else to help maintain it. The person that helps maintain all of those things, they also have a double burden of maintaining your life on top of their own. It trickles down to your family, friends, social life and especially your physical and mental health, because you’re not able to make doctor’s appointments.

The long hours are also a serious health and safety problem because we’re wrapping really late after working 12 plus hours. We’re all very tired when we are wrapping and that can consist of driving home too tired to drive safely. There have been many car accidents, there have been deaths, and the list can go on. The conditions that we’re shooting in are sometimes not hygienic or safe, like shooting on streets and train tracks that have live traffic, like people having to run for their lives to literally avoid being hit by a train. An IATSE crew member, Sarah Jones was hit and killed by a train in 2014. That sparked a movement for more safety and oversight in the industry and since then I think people have pushed for safer working conditions.

Another thing that happens is something called “Fraturdays,” which is when they start shooting so late in the day on Friday that you don’t wrap until sometime Saturday morning so now your weekend has been encroached upon and you’re likely going to be called in early on Monday morning. So you don’t even get all of your Saturday.

There are also discrepancies in pay all over the place. For example, production assistants are usually paid minimum wage, and PAs are the worker bees, they do so much work. And they’re not in a union. They are hired to help manage all the logistics of the day and they make everything happen as it’s supposed to. They are often young and aspiring crew members that hope to someday be in the union, but they have to get a certain number of days under their belt before they can join the union. So they do this low paid work, they work the longest hours, they’re treated worse than other departments, and they are not allowed to sit down. It’s definitely a big part of the culture, you see them standing up and if they sit down, they pop up when one of their bosses comes. The saying is “a good PA never sits down”. So just to sit down a PA has to take a bathroom break, and there are stories of PAs having to stand so long and who take bathroom breaks just to warm up and get off their feet.

People find ways to sleep at work because they’re not sleeping at home. People’s mental health and social skills deteriorate towards the end of the week. People are fried, irritable, exhausted and not as productive and not as capable of taking on stressful situations, and that’s when you start to see the mean side of people that comes out in the industry. That is a big part of it. There is a lot of gaslighting that keeps people accepting these conditions and not trying to challenge them. We’re told that it has always been this way, which isn’t true. I’ve been talking to fellow IATSE members that have been in the union for 30 years and they say they remember a time when it wasn’t like this. So something has happened alongside the deterioration of unions in this country, and that’s how this has played out in our industry.

HAR: How are race and ethnicity connected to this strike? What impact, if any, have BLM protests had on your co-workers?

SS: This question is awesome. It’s something that hasn’t been really talked about. The BLM protests are like a precursor that gave people a place to express some of their discontent. A lot of issues came out during the pandemic and the protests when organizations were forced to look at whether their systems and protocols had bias or were racist, and they were challenged to look at that and make changes and our industry was one of them.

We created diversity committees and through that we were able to see the ways that racism and discrimination were playing out. And that whole experience sparked people to get involved, get political and share their thoughts on what’s going on. Through that, all of the other issues that we’re facing in our workplaces also started to come up. I think that the success of the Black Lives Matter movement—the success of just being able to now talk about politics at work, whether it’s racism or the conditions at work—I think that’s getting more normalized. So, it was sort of a natural flow that the next thing we start to talk about are the conditions at work and organizing around that.

I think there’s a level of confidence that people have, and some of that has come out of the connection we made building solidarity among our membership through the diversity committees. We now have a diversity and inclusion committee at the national level in IATSE and many locals have created their own. There weren’t many before and through that wildfire of committees popping up, I think we inspired our leadership to legitimize what we’re doing by creating a national committee and taking on some of the work that we were all doing as small locals. We’ve made a difference.

A lot of what happened during that organizing drive was rebuild solidarity among our members. There wasn’t enough of that before and now we have this connection with each other that we made through all that organizing, and that still exists and gives us confidence that we can support each other. It was often very difficult to organize people around social justice issues, and Black Lives Matter was the spark. It was a catalyst, for sure, and that meant we connected with other locals and crafts that we didn’t have strong connections with before. We work alongside these folks but we don’t always interact. We can be very compartmentalized.

Diversity organizing enabled us to break down those divisions and organize around something that affects all of us. It was really neat to see. Our local attended the March on Washington, organized study groups. It was exciting. We read Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor’s book From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation, and now we’re on to a book called 400 Souls edited by Ibram X. Kendi and Keisha N. Blain

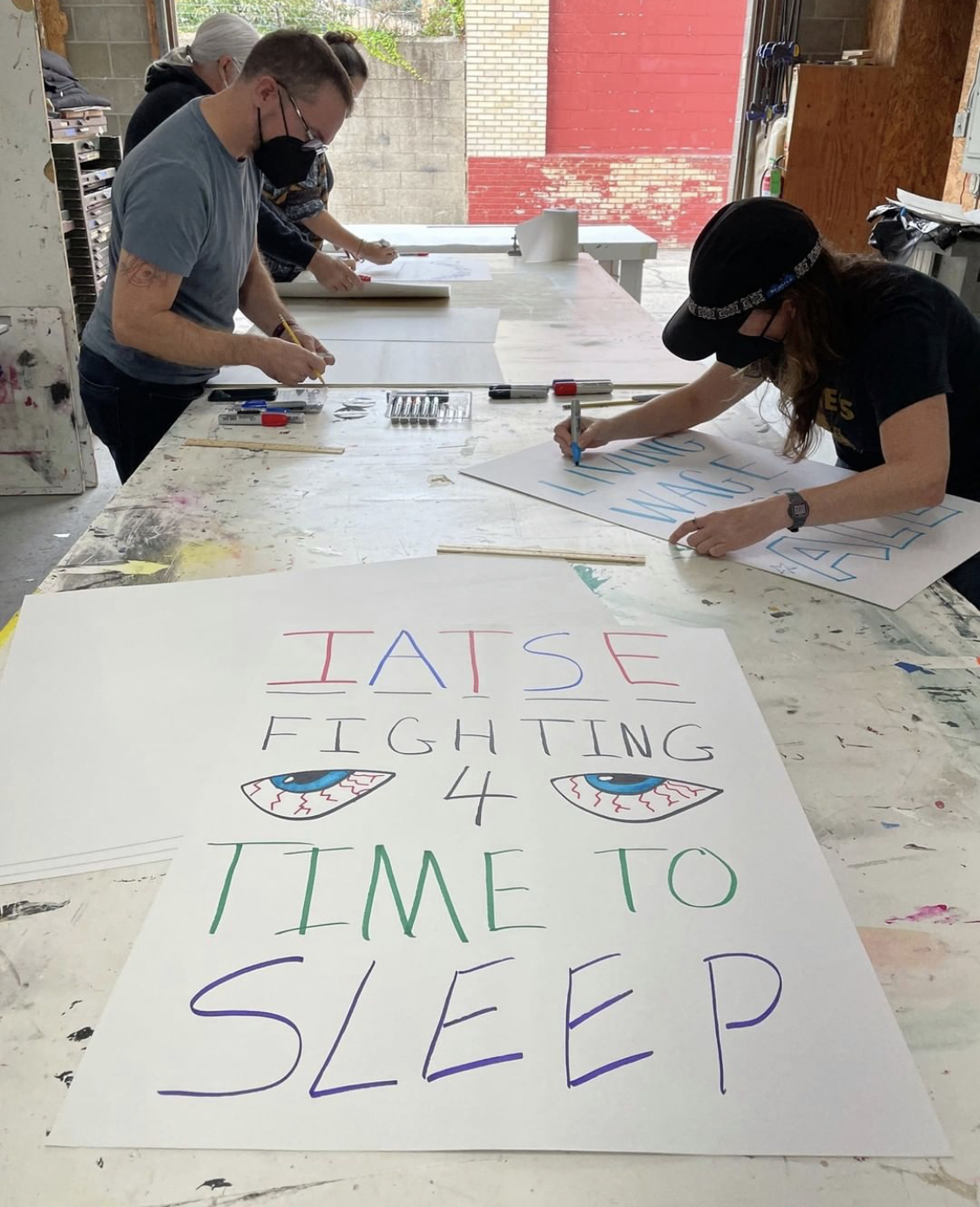

HAR: What are you and your co-workers doing to prepare for the strike on the ground? For example, we’ve seen shows of solidarity from unions. Does this mean that all TV/film production would shut down if you strike, with actors respecting the picket lines? How can the community and other labor unions support you if you go on strike?

SS: I would say that my co-workers are preparing for the strike once it’s called. There are a lot of legal restrictions on what unions can and cannot do. If there is a strike, the three locals that would strike in New York are locals 600, 700, 800. Cinematographers, editors, and mechanics. The rest of us on the crew, which is over a dozen other departments, are not required as individuals to cross a picket line. So our fellow members that are striking would be on strike, the rest of us would not cross the picket line. We’re not all on strike.

I’m trying to figure out how to support my fellow striking union members—who we share a workplace with but we’re not technically on strike with. I’m trying to figure out how to protect my union and how to protect ourselves as individuals from unwanted legal problems that would impact our ability to win the strike.

That’s the tightrope that we have to walk and an even tighter tightrope that our leadership has to walk. This will require a lot more grassroots communication and support because there is a media blackout. The activists will have to organize information campaigns on social media and rallies to raise awareness about the strike.

Many unions, like SAG-AFTRA, have all come out in support of IATSE’s struggle. Even Congress has come out in support of IATSE and the struggle for safer working conditions. We have a lot of support and the members are ready to strike. I hope that actors and people “above the line” will respect the picket line.

But we need the support, we need solidarity rallies from labor and from the community. We will need support on the picket lines and around the clock coverage of several locations. Each production is a different workplace, and they’re going to have a portion of the crew striking but an even larger portion of them not crossing the picket line. I think supporters and unions should plan to help with picket line support, and sign up for shifts if possible to maintain a well-attended picket line and a presence so that the press can see what we’re going through.

A lot of our workplace issues happen “behind the scenes.” They don’t see that PAs can’t sit down or that we can hit almost 40 hours in three days. That’s something that people can’t see, but if they see us all over New York, New Jersey, and Hollywood, out at all of these places, that would make a big impact. Since the vast majority of members haven’t been on a strike before, union and community support will be a huge help because we need the experience of those who have experience with workers’ struggles and striking. Our entire country is going through the motions of filling this experience gap and learning how to strike again.

Categories

We want to hear what you think. Contact us at editors@tempestmag.org. And if you've enjoyed what you've read, please consider donating to support our work:

DonateHéctor Rivera View All

Héctor A. Rivera is a queer, Mexican-American, socialist educator. He lives in Los Ángeles, Califaztlán. He is a member of the Tempest Collective.