Striking echoes in Iran

A report from the oil and gas strikes

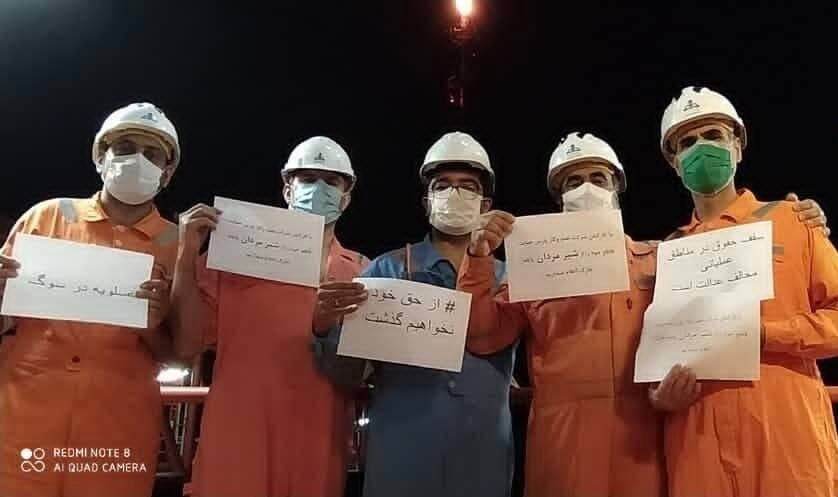

The ongoing strike by Iranian oil and gas workers—called the “1400 campaign” (the year 2021 in persian calendar) or the “10-20 campaign” (10 days rest for 20 days of work)—is distinctive in its scope and level of organization. It also marks an inflection point in the struggles of Iranian workers in recent decades, while holding powerful historical echoes from the 1979 revolution.

Since the beginning of the campaign, tens of thousands of workers in over 100 plants in 15 provinces have joined the strike. Many workers in other industries, such as bus and truck drivers, steel workers, teachers, and municipal workers in different cities have also gone on strike and joined the campaign, even if for just a few days.

The strikes began on June 19, 2021 when a group of workers in Bidqoon power plant in Asaluyeh halted production and walked out in protest over low wages and harsh working conditions. In a span of just a few days, their strike spread to other plants across cities with rich reserves such as Kharg, Abadan, Ahvaz, Qeshm, Kerman, Urmia, Behbahan, Gachsaran, Tehran, Arak, amongst others.

Revolutionary resonance

There is an historical irony, or promise, with the start of this strike wave. Two days after its start, the masquerade of the presidential elections, marked by the mass abstention of working class voters, concluded with the predictable victory of Ebrahim Raisi. Raisi was in charge of murdering thousands of communists, radicals, and revolutionaries in the 1980s. And it was oil and gas workers, by closing down oil pipes and staging a general strike in fall 1979, who played a key role in advancing the revolution and shaping the future of the Middle East.

In January 1979, puppets of capital gathered in the Guadeloupe Conference and resolved to tighten the green belt of Islam around the region as a bulwark against the advance of socialism. Khomeini, certain of America’s support, promised worker management and control, and a soviet-type government to the workers and turned their strikes into a means for empowering the clergy. After taking power, however, he suppressed the strikes and murdered the leaders of workers with the aid of the likes of Ebrahim Raisi (a member of the Death Committee in the 1980s). The revolution that has been dubbed as one the “central revolutions of the twentieth century” was defeated. Thousands of revolutionaries were murdered, and those who survived either fled the country or went into hiding. The Iranian left was decimated and the counter-revolution successful.

42 years have passed. No one could have imagined that on the same day when one of the most ruthless killers of workers and revolutionaries wins the presidential race, oil and gas workers would strike again. It seems as if history has brought the actors of 1979 back to the field of battle to settle old debts. Part of the most determined and radicalized workers i.e. the oil and gas workers have erected the flag of the general strike against the most criminal of the clergies.

In a previous article, we described the growth and radicalization of the Iranian labor movement over the past decade. Amongst the most militant have been sugar cane workers in Haft-Tapeh, truck drivers, bus drivers in Tehran, and teachers. Despite the hopes and expectations of many of these workers, oil and gas workers have not taken a central part in these strikes and have only staged sporadic and unorganized protests. Their largest and most successful strike happened last summer when thousands of the oil and gas workers in South Pars forced employers to improve their wages and living conditions.

Labor Conditions in the Petrochemical Industry

The industrial rise of Asaluyeh (an example of a broader pattern) dates back to 1998, when the Pars Special Economic Energy Zone (PSEEZ) was established to develop the South Pars Gas Field, the world’s largest gas field, that lies in the Persian Gulf and is shared by Iran and Iraq. One section of PSEEZ constitutes an area of 14,000 square miles in and around Asaluyeh (other sections of similar size are in Kangan and Bushehr) in the Bushehr Province with special economic laws aimed at encouraging private and foreign investment, industrial development and boosting exports. Since 1998, thousands of workers have come to Asaluyeh to seek employment in gas and petrochemical plant construction, transport, refineries, and the port.

While PSEEZ has filled the pockets of employers, private contractors and government officials, it has brought nothing but misery for the workers. Since PSEEZ is exempt from labor law, workers live and work under extremely difficult conditions without any legal means to defend themselves. They live in dorms that lack the most basic sanitary requirements with often 10 workers jammed into a room of just 40 square meters. According to a striking painter in Asaluyeh:

There are 400 people in our dorm with next to no facilities. Nine of us sleep in each room and we often hit each other while sleeping since there is not enough space … There are only four bathrooms and five showers. We leave at six in the morning for work and get back around 7:30 in the evening. After a hard day’s work in a polluted environment, each one of us has only two minutes to take a shower while 10 others are waiting in line … sometimes I think the situation in prisons might be better.

They work under temperatures that reach as high as 60 Celsius (140 Fahrenheit), and job related accidents frequently result in deaths. A striking worker describes a typical working day:

You wake up at six in the morning. The weather is terribly hot and humid. The bus to work has no air conditioning and has a horrible stink since many workers weren’t able to wash their clothes out of exhaustion. Half an hour later, office workers, with their clean and ironed clothes, come to work in a stylish air-conditioned bus. My job is to walk around and check the machines. Humidity and heat is so high that it only takes 15 minutes under shade for your clothes to be dripping with sweat. At 1 PM you go to the bus stop to go for lunch. There are long lines and everyone rushes to get on the bus. The dirt, dust, exhaustion, heat and traffic drives you crazy. Inside the bus is like hell, like hell!! The bus drops you off at the dorm and you have to run to get some food, most workers don’t even have time to wash their hands. I often have to stay on site because of overwork and they bring my lunch to work: a boiling soda and stale meat. The worst part is that you see your own sweat dripping on to your food but are too hungry to care … After dinner you go to your room to listen to the hallucination of young coworkers high on drugs. It is so sad, it makes me cry … You should just know that they keep us like animals. They have no concern for the safety, health, and nourishment of human beings. The news of this strike brought tears of joy to my eyes. I’m so excited and hope from the bottom of my heart that these strikes will end with a victory for the workers.

The precarious position of the workers is exacerbated by the privatization and outsourcing of the sale and purchase of their labor-power to hundreds of subcontractors. In Iran between 80-90% of workers are on temporary contracts and have no secure employment. Among them, contract workers have the worst conditions. They are not directly hired by the employers but by contractors who buy their labor power far below its value and sell it at a profit to the plant owners. In contrast, formal workers have secure and permanent contracts, receive wages that are 3-5 times higher than temporary and contract workers, and the laws of special economic zones do not apply to them. According to the editors of Sarkhat (a Telegram news channel):

If you are a contract worker in the oil and gas industry, your wage is below that of the formal workers. You are robbed of many insurance services such as retirement. Your vacation time has already been determined by subcontractors and is less than formal workers. And most importantly, your period of employment has already been determined by the employer or the subcontractor. Usually after a period of one year, your employment depends on the whims of the subcontractor. Subcontractors easily avoid providing you with insurance, they constantly change your workplace, and they can terminate the contract. In a word, they control your work life.

A striking welder from Tehran explains in an interview:

Our first demand is to be workers. We don’t know if we are workers or slaves. There are no laws and we have no benefits, nothing. Some subcontractors don’t even give us a contract, we don’t know for how long we are employed. If we are to be workers there needs to be some laws. They often don’t pay us for up to six months.

The strike is being led by skilled manual workers such as welders (who began the strike), cutters, scaffolders, fitters, molders, electricians, installers, and warehouse keepers. Office workers, most but not all of whom are formal workers, have for the first time declared their support for the strikers but have not joined them yet. The vast majority of these striking workers are temporary (hired for a specific project or a period of time) and contract workers.

The Struggle Between Labor and Capital

In its first statement on June 20, the Organizing Council of Contract Oil Workers— while not an elected representative council of workers, a virtual body of some of the most conscious workers seeking to cohere and inform the strikers as a whole—put forward their list of demands:

1) No oil worker should receive less than 12 million Toman (2850 dollars) a month and the level of wage must increase immediately. Wages should continue to increase with inflation.

2) The delay in payment of wages is a clear act of robbery. Wages must be paid on time every month.

3) We object to temporary and contract work and demand the elimination of subcontractors. We want to have job security and permanent contracts. Dismissal of workers must be prohibited.

4) The laws of special economic zones that have given unlimited powers to the employers to interfere with our lives should be suspended immediately.

5) We demand a safe working environment. Our current conditions are like an explosive bomb: terrible fires, falling from heights, noise pollution, inhaling chemical and toxin material, below standard clinics, working under intolerable heat in the absence of air conditioners and cooling equipment.

6) It is our right to unionize and protest. We are tired of the policing of our workspaces.

Employers have either refused to meet demands or, similar to last year, have only made empty promises. From the beginning of the strikes, they have resorted to a variety of strike breaking tactics. First, they cut the water in dorms and stopped feeding the workers in order to push them out and hire new workers. Many workers left the dorms to be with their families but the Organizing Council, in their second statement issued on June 26, warned the workers:

You have seen that where our colleagues have left their dorms and gone home, merciless employers are preparing to hire new workers. If we stay in our dorms, the employer will not be able to house new recruits, and with our presence they will not have the courage to expel us. Our suggestion is that we should come back to work after spending a week with family and be present at the plant to continue our protest.

The statement went on to encourage active participation and collective decision making:

We must not let a few people make all the decisions while we all go home. But whether by staying at dorms, planning the picket line in front of the refineries, or by active participation in social media, we must be actively involved in the development of our struggle. This is an important lesson we learned from Haft-Tapeh sugar-cane workers, and we must know that it is only by collective decision making through our councils that we can fight against their divisive tactics.

Employers have tried to force the strikers back to work, using a second tactic: threatening to fire them or making false promises. On June 22, just three days into the strike, 700 workers in the Tehran refinery were dismissed. In response, the Organizing Council encouraged unity in their third statement issued on June 27:

As our strike moves forward with great force, employers and contractors are conspiring against us. In some places they are threatening workers that if they don’t finish ongoing projects, they will be fired. In other places they are trying to calm the workers by organizing meetings with local imams and government officials … We must stand united against all these tactics and inform others through social media … You should tell them that you are part of a general strike and will not accept any conditions. And if you fire us you will have to face thousands of striking workers.

The third tactic of the employers has been to take advantage of the decentralized nature of the strikes to form representative bodies to negotiate for the workers. This is precisely how, immediately after the revolution, by introducing Islamic Councils, Khomeini neutralized independent worker councils. The Organizing Council denounced this tactic in its fourth statement issued on July 4:

The record of Islamic councils is clear to the workers. These have always been, and will continue to be tools to control us in service to the employers. … Similar to our sugar-cane colleagues in Haft-Tapeh, steel colleagues in Ahvaz, and others, we definitely declare our opposition to Islamic councils

In their fifth statement issued on July 6, the Organizing Council responds to offers made by employers and subcontractors: “Some of us contract workers discussed this issue. Our condition for considering or accepting any offer is that it should be official, in writing and announced publicly.”

In its following statements, the organizing council continues to warn against bodies such as the Piping group that try to co-opt the movement and water down the demands of the strikers. In their tenth statement issued on July 23, the Council reiterates their core demands and warn against Piping’s attempt to end the strike:

The leaders of Piping have put forward a poll to end the strike without even having put forward our demands. … It is obvious that any strike has a beginning and an end. But it is us the workers that should determine the end of our strike. … What gives meaning to our strike is our shared demands and victory depends on the enforcement of these demands … The most important factor in pursuing these demands is our own active involvement. Strikers in different plants should elect representatives to negotiate on their behalf. Through social media we can continue these conversations and elect workers to represent us. … Colleagues! This is the only way forward, to remain united and make democractic decision through our councils.

The future of the strikes remains uncertain. While the Organizing Council tries to guide the strikes, it is not a centralized organizing body nor does it officially represent the workers. In the absence of a strike fund it is unlikely that workers can continue much longer. On the other hand, most of these workers have nothing to lose and they know that the moment the strike is over, employers will walk back on all their promises. The entrance of formal workers could change everything, but the government has so far held them off by promising higher wages and better working conditions.

Growing Class Consciousness

It is true that many of the statements that circulate in Telegram channels (similar to Whatsapp or Signal groups) are written by the more conscious and militant layer of the workers and do not represent the entire class. But many of these channels have up to 5 thousand members and act as conduits to dissemination of information. One can find many videos of workers on the picket line, protesting in the streets, speaking in their assemblies, and sending solidarity statements to one another. For example, on July 11 welders in Hafshejan published a video announcing the decision made by their general assembly to continue the strike until their demands are met. The next day, project workers in Izeh formed their own general assembly and published a video to announce their solidarity: “Dear our Hafhsejani brothers, we heard your call. Until our demands are met, we will proudly stand by you and all the industrial workers in Iran.”

Just a few days later, workers in Fars, Bakhtiari, and other regions, followed up with their own videos of solidarity announcing their decision to continue the strike.

Statements of solidarity have been issued by workers from across the country (including teachers, students, journalists, retirees, and nurses). They sympathize with the workers, talk about their shared suffering, and give advice based on their own experience. On June 27, in a joined statement of solidarity, two of the most militant unions (along with 9 others) or 11 unions and worker syndicates including, Haft-Tapeh Sugar Cane Labor Syndicate and the Syndicate of Workers of Tehran and Suburbs Bus Company, emphasized the importance of establishing a strike fund for the continuation of the strike:

Dear petrochemical striking contract and project workers! As you have understood … we can only achieve our demands with unity and solidarity … we send you our warmest regards and will learn from your experience to further our struggle … unity amongst workers and the attempt to create a strike fund for striking workers is an urgent necessity for the continuation of this struggle … We ask all the workers, retirees, teachers, students, intellectuals, artists, journalists and all the working and honorable people of this country to support this righteous movement.

On July first, the National Union of Truck Drivers, who are directly impacted by the strikes as their access to fuel has been limited, issued a statement of solidarity encouraging formal workers to join the strike:

We, the road and transport drivers, in addition to supporting all the rightful demands of [oil and petrochemical] contract workers, ask that formal workers also join in the strike because the source of all our suffering is the same. We declare, in support of the protest movement, that if the demands of these honest and hard working workers are not met, we, the drivers, will join this strike across the country.

Three days later they staged a one day strike. Over the past month, many truck drivers in Isfahan, Shiraz and other cities have participated in the strike.

Ethnic divisions have been used by the government to divide the workers, but there are signs that workers are overcoming these divisions. A South Pars worker, after describing their own miserable working conditions, goes on to say:

Now consider all these inhumane conditions and know that our situation is a hundred times better than unskilled daily workers in Balochistan. They have no rights, no insurance, no dorms, nothing. Not only are they exploited by the state, employers, and the contractors, but are also ethnically and racially oppressed … Even slaves had better living conditions.

With the growing protests in Khuzestan, the Organizing Council issued a statement of solidarity with the protestors:

The demands of the people of Khuzestan are our demands. Profit-seeking policies and the greed of government officials have destroyed the environment and abandoned the people to their fate … we share these pains. The tormented people of Khuzestan are voicing the grievances of all the people and workers of Iran.

Whether or not the strike is successful, a threshold has been crossed. Skyrocketing inflation, environmental degradation, and crumbling infrastructure have brought the country to the brink of collapse. Protests and strikes are growing across the country, and thousands have come to the streets in support of the people of Khuzestan. The slogan that four decades ago drove the Shah out of the country can be heard in hundreds of cities: “Death to the dictatorship!”

Categories

We want to hear what you think. Contact us at editors@tempestmag.org. And if you've enjoyed what you've read, please consider donating to support our work:

DonateNasrin and Sam Salour View All

Nasrin is a writer and activist in Iran. Sam Salour is a writer and activist in New York City and a member of the Tempest Collective.