Defeat in Bessemer

A wake up call for the Left and labor

It seemed like everything was set for victory. A large, powerful corporation that took advantage of poverty wages paid in a southern state. Union organizers who countered company propaganda by highlighting connections between “civil rights and union rights” to a predominately African-American workforce. A host of celebrities and politicians who pledged support for the union drive.

What could go wrong?

When the votes were counted, however, the union suffered a crushing defeat. Workers rejected the union by a two to one margin. Confusion gripped many across the country who had hoped for victory. Why would workers reject a union? Organizing the South—the long elusive goal of the U.S. labor movement—appeared to be, once again, postponed to the indefinite future.

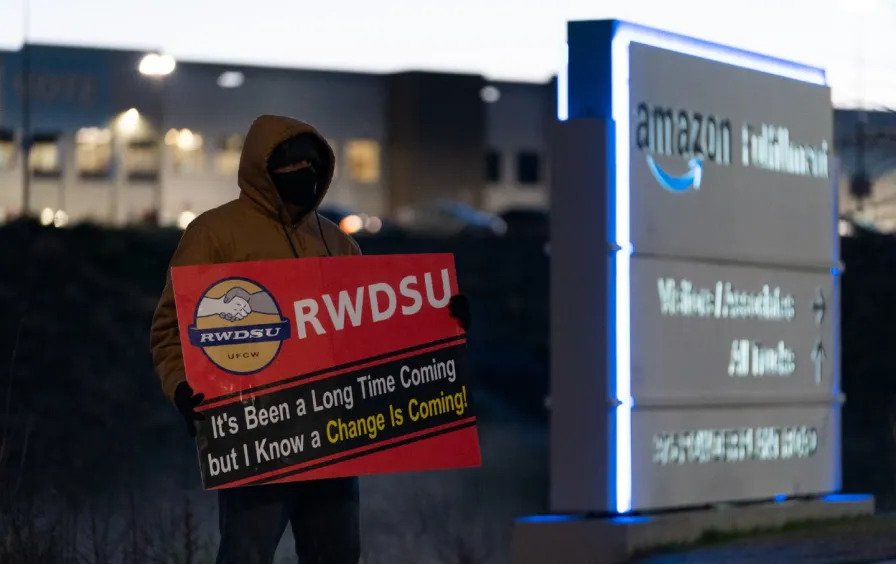

The Amazon warehouse at Bessemer, Alabama, in 2021, you ask? No. It was the United Auto Workers (UAW) defeat at global automaker Nissan in Mississippi in 2017. Was the Retail, Wholesale, and Department Store Union (RWDSU) defeat at Amazon foreshadowed by the UAW four years earlier? In its broad outlines, yes. However, the RWDSU had previously led several successful organizing campaigns in Alabama; it appeared to know the southern terrain better than the UAW which makes the sting of defeat even worse.

Walmart and Amazon are the two largest private sector employers in the United States. Amazon and Apple are the first trillion dollar corporations in history. Unions historically identified with the Left, like International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU), those identified with the business-union Right, like the Teamsters, and huge mediocrities like United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW)—all have failed to pierce the shield of the retail, tech, and logistics corporations that dominate the U.S. economy.

The latest defeat at Amazon shows that there are problems plaguing the beleaguered unions that go beyond the relative efficacy of various organizing models or the challenge of countering the well documented methods of union-busters. This is not to let RWDSU off the hook for the mistakes they made in Bessemer. The union had 30 percent of cards signed with a smaller bargaining unit of 1,500 workers; only to find Amazon demanding and winning that the bargaining unit be expanded to 5,800.

This is one of the long established methods of defeating a union drive and it could have been anticipated. A behemoth like Amazon has greater power to define the limits of what the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) might recognize as the contested bargaining unit. More important, Amazon has resources to reach every worker, and to target certain groups of workers, while union organizers and volunteers face greater challenges. RWDSU always seemed out-staffed and out-gunned by wealthy and politically-connected Amazon. Due to the pandemic, organizers chose not to do house calls, one of the proven methods in organizing drives. That the union did not make the difficult decision to postpone the election to a more advantageous time seems to be a blunder in retrospect.

Did all of the extensive anti-Amazon media coverage go to people’s heads? I have never witnessed such extensive and pro-union media coverage for a union representation election. The Bessemer campaign was hyped as a “test case for labor” with little serious examination of the prospects for a relatively small union like RWDSU to defeat Amazon. While left-wing academics who specialize in labor and left history in Alabama also contributed to distorting the picture on the ground by under-playing the discontinuity between the early 20th century and today.

Tempest was one of a few Left publications that tried to put forward a more modest perspective on what could be expected from the Amazon campaign, and, even then, it fell below our expectations. There is going to be a lot of explaining to do. Debates on the Left and in the labor movement will be quite sharp, if not nasty, as union leaders, staffers, and their academic allies try to weasel their way out of responsibility for this fiasco.

Even before the deadline for ballots was reached, RWDSU President Stuart Appelbaum said, “With their historic campaign, Amazon workers have already won. It’s up to all of us to build upon their victory.” Declaring victory before a vote count is always a bad sign. After the vote, he said, “We won’t let Amazon’s lies, deception and illegal activities go unchallenged, which is why we are formally filing charges against all of the egregious and blatantly illegal actions taken by Amazon during the union vote.” What happened to the victory?

Still, the problems run deeper. U.S. unions have been selling a brand of unionism that workers, especially industrial and warehouse workers in large workplaces, have not wanted to buy for many decades. Look alone at the string of defeats in the South from Volkswagen to Nissan to Amazon. The last time there was serious discussion of a union drive at a major logistics employer, FedEx, it followed the victorious Teamsters strike at UPS in 1997. This talk was ended by the federal government intervention against Teamster leader Ron Carey.

Meanwhile, the big industrial unions have concentrated for the last four decades on “protecting” unionized employers against non-union competitors at the expense of their membership by permanently enshrining wage and benefit concessions in contracts. This has led to the worst of both worlds: unionized workers frustrated at weak unions and non-union workers largely turned off by a labor movement that offers little better than what they already have.

Media coverage of working conditions at Amazon has been extensive—stories of drivers urinating in bottles, back breaking work in distribution centers, extensive violations of health and safety regulations, and workers dying from heat related illnesses. These conditions are reminiscent of those at United Parcel Service (UPS),the largest private sector employer in the U.S.

The Teamsters have represented warehouse workers and truck drivers at UPS for over eighty years—workers whose working conditions are the most akin to those at Amazon. If the Teamsters are not an appealing alternative for Amazon workers, why would the tiny RWDSU have a chance? Why would the Teamsters be an appealing option, given the decades of retreat and concessions following the defeat of Carey and the reform movement? Carey himself recognized this years ago:

You cannot attract new members when you’re selling out the ones you have. I also know that when union leaders forget where they came, and aren’t doing the job, history has shown that members will fight for change.

A conclusion many will draw coming out of the defeat in Bessemer will be the need for renewed emphasis on calls for a push for the PRO Act, an ambitious attempt at labor law reform. It is worth noting that the labor movement has been chasing labor law reform for four decades, coming up empty handed each time. The criminal behavior of Amazon during the union drive has been predictable. Indeed, it is a testament to the need for labor law reform. However, there is nothing that has prevented unions from organizing Amazon workers more than the passivity of the unions. The unions have largely been bystanders since the beginning of the massive expansion of the Amazon warehousing and distribution network a decade ago, long before it became the behemoth that it is now.

Workers want fighting unions. Anything short of that means that workers may be sympathetic but largely immune to appeals to organize because they are not willing to risk the little they have in a contest for power at work. This is especially true in those parts of the country, like Bessemer, where the old industrial, unionized jobs disappeared years ago and Amazon is one of the only games in town. The proud union traditions that once existed in such places are far removed from the current generation of workers who have only experienced chronic poverty and unemployment.

There is a grand canyon that separates the industrial and retail unions and the work lives and struggles of the industrial workers in this country. This is not nostalgia for the rank and file rebellion that rocked the industrial core of the economy in the 1960s and 1970s. It has been a long time since both the Left and the labor movement have tried to organize a big industrial corporation like Amazon. This is a time for serious reflection and debate, time for a plan of action. Amazon is not going away.

Categories

We want to hear what you think. Contact us at editors@tempestmag.org. And if you've enjoyed what you've read, please consider donating to support our work:

DonateJoe Allen View All

Joe Allen is a long-time labor activist and writer. His latest book is The Package King: A Rank and File History of UPS.